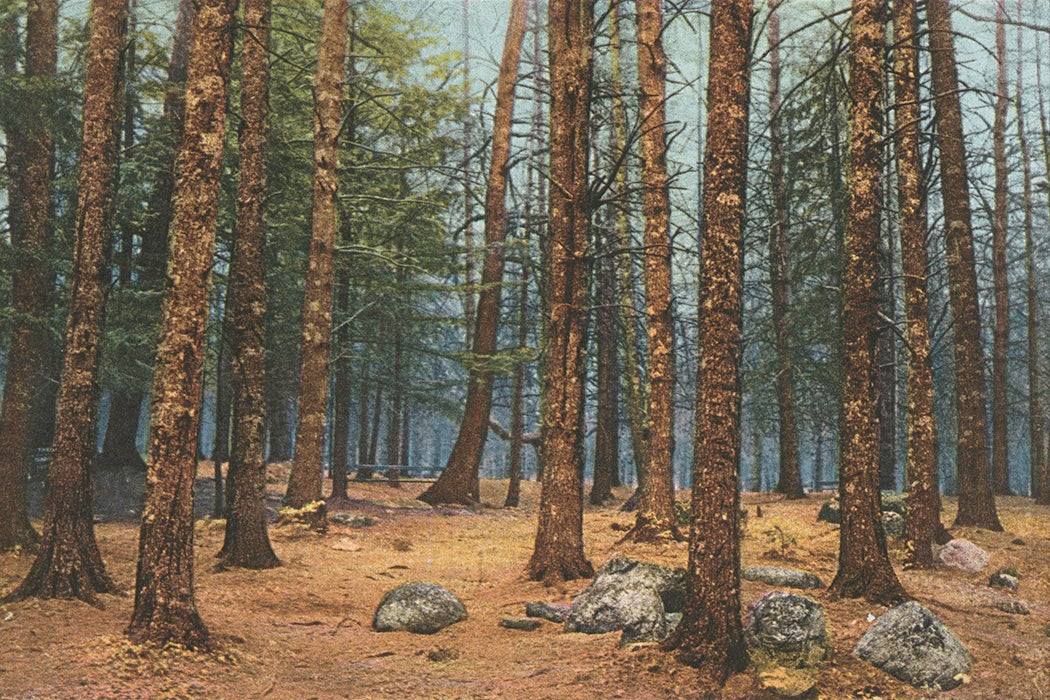

J. Russell Smith stood on a crest above the Corsican hillside and admired the forest of chestnuts that lay before him. It was the 1920s, and around the world modern agriculture was coming to be defined by tilling and plowing—processes that damaged soil health and disrupt natural landscapes in service of annual crops that required the cycle to persist, year after year, degrading the land ever more.

But here in the Mediterranean, these chestnuts had lived for centuries, providing nourishment for humans and animals as well as timber for shelter and economic sustenance. What was more, “the mountainside was uneroded, intact, and capable of continuing indefinitely its support for generations of men,” Smith wrote in his sixth book, Tree Crops: A Permanent Agriculture, published in 1929. He saw “an enduring Eden” that offered something better for both agriculture and our relationship with the land, built upon “soil-saving tree-crops.” And he committed himself to supporting its spread—a return to farming methods that saw humans in harmony with nature rather than attempting to tame it.

In Tree Crops, which has endured much like the “broad-topped, fruitful” Corsican chestnuts, Smith described the myriad benefits trees offered the world of agriculture and urged a revolution in their use. The tree, he believed, is “an engine of nature,” and we should put it to work to serve both ourselves and our environment. The book—one part treatise on the agricultural potential of trees, one part lament for the state of the world’s soils—implored readers to change the food system before it was too late.

“We are today destroying the most vital of our resources…faster and in greater quantity than has ever been done by any group of people at any time in the history of the world,” Smith wrote. “If our people could be made to feel this, they would try to stop it.”

A century on, far more land has been ruined by industrialized farming practices, including deforestation, excessive fertilizer use, and livestock overgrazing. One-third of global land is used for agriculture, and one-third of that share has been degraded by human use, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. But a new generation of farmers are heeding Smith’s call, breathing new life into the vision of “the apostle of tree agriculture” by investing in agroforestry—the integration of trees into agricultural systems for the benefit of farmers, animals, and the environment. All these years later, Tree Crops is the central text for those engaged in the practice, many of whom see transformative potential in restoring trees to their rightful place as keystones of sustainable agriculture.

* * *

Smith was born into a middle-class Quaker family in 1874 in Lincoln, Virginia, where he was active on the family farm and, from an early age, developed a close relationship with the land. He inherited his father’s penchant for experimenting with crops in search of the best varieties—a practice that became central to his pioneering of tree-crop agriculture. He was intent on work that improved life on earth for all humanity, guided by the Quaker notion of world brotherhood. To Smith, the destruction of land was an affront, and he felt deeply the impacts of degraded soil.

“The forest fire burns me, a gully hurts me—no matter whose land it is on,” he wrote elsewhere. “It is an injury to the human race.” (Tree Crops was “primarily an attack upon the gully”—scarred earth riven by water coursing over eroded soil.)

Smith went to the Wharton School in Philadelphia to prepare for a career in economics before his path was altered by a job evaluating the development of routes across the Isthmus of Panama at the turn of the century. Lacking the geographical expertise he thought necessary to do the work right, he committed to studying and teaching geography so future generations would be better positioned. He earned a doctorate in economic geography and turned to a life as an educator and textbook author. But while traveling around the world in the 1920s to gather information for his books, he encountered an issue even more urgent: soil suffering at the hands of modern agriculture and deforestation.

In Tree Crops, he described standing on the Great Wall of China near the border of Mongolia, gazing out over the “gashed and gutted countryside.” Once good farmland, the whole valley was now “a desert of sand and gravel, alternately wet and dry, always fruitless.” There was a lone tree nearby, a reminder that the area had been forested before it was cleared by farmers who plowed the land, allowing rains to wash away the loosened soil. Now, all that remained were ruins, nothing but “a wide and sickening expanse of gullies.”

More to Explore

Tree of Peace, Spark of War

Smith saw the forest, field, plow, desert cycle not just in China’s hills, but in so many places, including his home country, where, in his estimation, the rate of soil degradation was speedier than it was in any place humans had ever settled. The tilling of crops like corn, tobacco, and cotton left soil susceptible to powerful storms. The result was field wash, which Smith deemed an unparalleled waste of resources, taking with it the basis of civilization and life itself.

“A burned city can be rebuilt,” he wrote. “A field that is washed away is gone for ages.” To Smith, the irreparable destruction of soil erosion was “man’s greatest crime against his environment.”

In trees, Smith saw salvation.

* * *

When he was still in his twenties, Smith bought a 130-acre farm in Virginia on the rocky slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains, attracted by the black walnuts and chestnuts that populated the land. He operated the farm as a business with a bent for scientific management. Like his father before him, he sought the best parent trees he could find to breed better-quality plants, running regional contests to see who might supply the sweetest honey locust or most fruitful acorn-yielding oak. The chestnut was his priority, but he also experimented with pawpaws, persimmons, mulberries, and more. Sheep, pigs, and cattle grazed under the trees and harvested their own fodder—a practice known as silvopasture, derived from Latin and meaning forest feeding. He sold the farm in 1951; by then, it was home to more than 100 nut and other crop tree varietals spread over more than 2,000 acres.

As a tree-crop devotee, Smith saw a solution to the soil problem and a better way forward for agriculture writ large. Trees, he knew, are better able to manage drought and heavy rainfall than the cereals and other annual crops that had become agricultural mainstays.

“Trees living from year to year are a permanent institution, a going concern, ready to produce when their producing time comes,” he wrote. He wanted to see the chestnut forests of Corsica recreated across the country, simultaneously preserving soil health and ensuring a prosperous future for humanity.

“I see a million hills green with crop-yielding trees and a million neat farm homes snuggled in the hills,” he wrote. “These beautiful tree farms hold the hills from Boston to Austin, from Atlanta to Des Moines. The hills of my vision have farming that fits them and replaces the poor pasture, the gullies, and the abandoned lands that characterize today so large a part of these hills.”

Smith wanted every crop-bearing tree to be improved to maximum efficiency by plant breeding—work he suggested would require the development of a new profession: botanical engineer. His vision included “an institute of mountain agriculture,” which would find suitable parent trees, hybridize them and test them by the ten-thousand, while promoting tree crops in the public consciousness and studying their impact on soil erosion.

In tree crops, Smith saw varied potential. The honey locust delivered sugar, the mulberry served as fodder for pigs and chickens, and the persimmon offered pasture and “a kingly fruit for man.” Chestnuts were “to the Corsican mountaineer what corn is to the Appalachian.” They could be a staple crop, along with walnuts (the “meat and butter tree”), but the possibilities didn’t end there. “Now that we know how to breed plants,” he wrote, “we need the systematic examination of all the trees of the country with regard to their present or potential crop possibilities.”

Tree Crops was a manifesto for a new way of thinking about agriculture and its relationship to the land. It argued for long-term investment in healthier systems, rather than short-term plunder.

“It will take time to bring this miracle to pass,” Smith acknowledged. “It will take time to work it out. First of all a new point of view is needed, i.e., that farming should fit the land.”

* * *

Nearly a century after Tree Crops was published, the point of view Smith advocated has taken root. Agroforestry is gathering momentum, and his book remains “the Bible” for many working to advance its practices, according to Austin Unruh, the CEO of Trees for Graziers, which helps farmers establish silvopasture on their land. Smith’s writing is quoted on the websites of a range of newly established agroforestry operations, from chestnut farms to nonprofits working to kickstart the transition to tree crops. Matt Grason, a member of Pennsylvania’s Keystone Tree Crops Cooperative, describes the book as “a nexus of the community in the US”—a text that nearly everyone in the field has some connection to.

“The book is a great reference, but more than that it really does serve as a reminder that the issues we’re tackling are not new,” says Kevin Wolz, the former co-executive director of the Savanna Institute and current CEO of Canopy Farm Management, its for-profit spin-off. “This is a longstanding issue—an agricultural problem that has deep roots—and it’s going to take a systemic and systematic strategy to deal with it.”

Where Smith once dreamed of an institute of mountain agriculture, there are now several. The University of Missouri operates a Center for Agroforestry; Virginia Tech has an interdisciplinary team devoted to the practice; and the Savanna Institute, a Midwest nonprofit, conducts plant breeding, research, and education with the aim of developing perennial agriculture systems centered on trees. All three are partners in a new initiative focused on expanding agroforestry production and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the agriculture sector, funded by a $60 million investment from the US Department of Agriculture. Among its objectives is the creation, over a five-year period, of 30,000 acres of new agroforestry plantings while expanding the market for tree crops like nuts and fruits, as well as for livestock products produced in silvopasture settings.

Weekly Newsletter

The timing isn’t coincidental. In addition to its potential to fix some of the flaws in our food system and preserve the soil that so concerned Smith, agroforestry has a role in addressing climate change. Adopting agroforestry practices—in the form of silvopasture, windbreaks, alley cropping, and riparian buffers—on just 10 percent of agricultural land could offset up to 30 percent of the United States’ annual emissions. It would also benefit rural communities by bringing new economic opportunities, increasing biodiversity and climate resilience, and decreasing agricultural pollution, researchers have shown.

As with all work involving trees, reaching that point will take time—decades of commitment to research, experimentation, and implementation. Smith knew this better than anyone. But with a growing community of practitioners and at least a modicum of government support, the vision he laid out in Tree Crops is coming into focus. If it ever comes to fruition—all those hills studded with crop-yielding trees—its legacy will be traced back to a geographer from Virginia who was called to serve the soil.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.