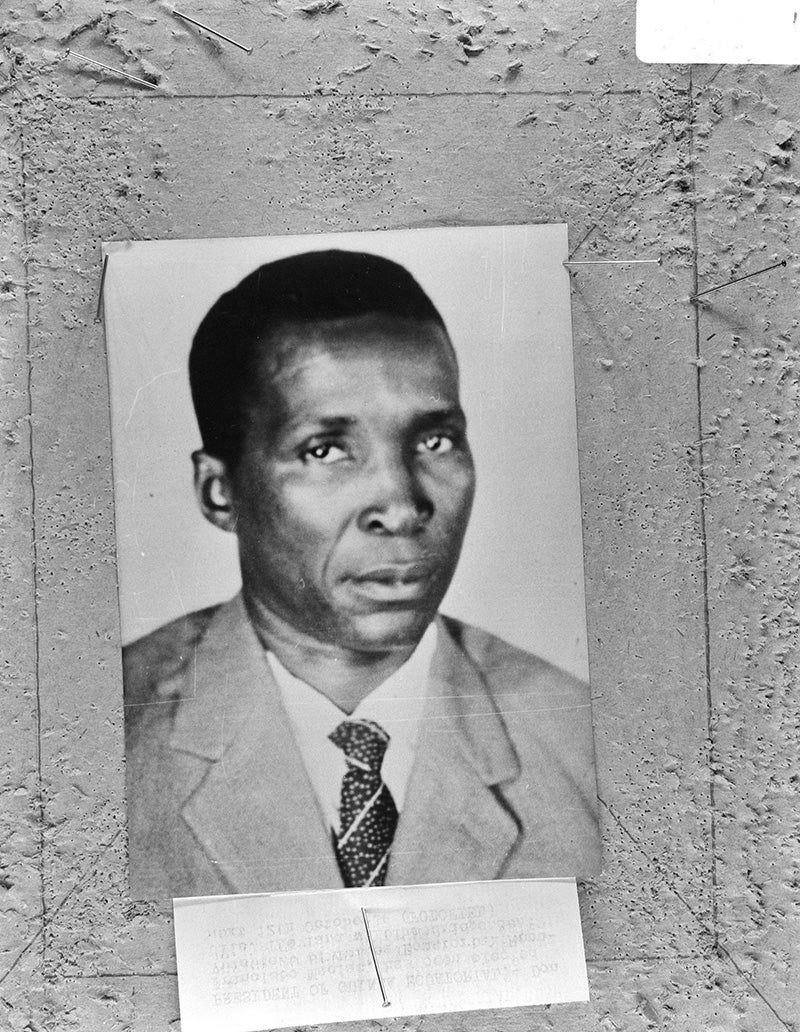

By the time of his execution in September 1979, it was estimated that, of a population of 300,000, more than 50,000 had been killed and 125,000 had fled to neighboring countries. Put on trial before a military tribunal and found guilty on 474 counts of murder (as well as embezzlement of public funds, material injury, and systematic violations of human rights) was Equatorial Guinea’s first post-independence president, Francisco Macías Nguema.

Macías, as he was commonly known, may not have the infamous “tank top tyrant” reputation of other 1970s African leaders such as Idi Amin and Mobutu Sese Seko, but the story of his genocidal rule was enough to make one foreign observer, Robert au Klinteberg, describe this small West African nation as a place where “ruthless and ambitious exposure of enemies of the State [was] a matter of personal survival.”

Constituting a small, rectangular slice of the west coast African mainland and five islands, the largest of which is called Bioko, Equatorial Guinea remains the only Spanish-speaking country in sub-Saharan Africa, the result of a colonial carve-up between Spain and Portugal in 1778. That year, the Treaty of El Pardo ceded commercial passage to the Bight of Biafra to Spain in exchange for Portugal receiving a vast land share of what is now western Brazil.

The colonial powers back in Madrid never did exploit Biafra, and by the turn of the twentieth century, the territory which had become known as Spanish Guinea consisted of the continental enclave of Rio Muni and the quintet of off-shore islands, the latter used as forced deportation points for enslaved people, manacled and bound for the Americas.

Attitudes among the Spanish toward their sole sub-Saharan possession did much to empower the violently anti-colonial protests which would come in the 1960s, as Enrique Okenve Martínez explains in a 2016 issue of Afro-Hispanic Review.

“Whether we are dealing with generous or vilifying images of Africa during the late nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth,” Martínez writes,

to the Spanish, Africa was fundamentally North Africa. Not even the most liberal of Spanish intellectuals could envision any sort of comparison between Spaniards and black Africans who, without a question, were perceived as the lowest of peoples in the hierarchies of cultures prevailing at the times. The black Africans were too unknown, too distant and, above all, too alien so as to make any connection possible in the Spanish imagination.

Despite such beliefs, by the eve of independence in 1968, it appeared that the population of Equatorial Guinea was better placed than many nascent nations in Africa to enjoy a prosperous beginning to independence, as Ibrahim K. Sundiata reflected two decades later in an essay published in the African Studies Review.

“Spanish Guinea could be truly touted as a model of colonial development in the late sixties,” Sundiata writes. Quoting journalist Sanford Ungar, he notes that,

the country “was expected to capitalize on its European connections…to make early progress as a nation.” [The island of] Biyogo…had one of the highest literacy rates in Black Africa. In 1960, exports from Spanish Guinea (of which Biyogo was the mainstay) totaled more than $33,000,000, the highest level of exports per capita in Africa ($135). […] In 1968 the main island was not only an exporter of cocoa, coffee and bananas, but also possessed some processing industries such as chocolate and soap factories and palm oil works.

Macías was believed by Spain to be so weak and ineffectual that future economic benefits for Spain, even after independence, would be axiomatic. But such hopes for a prosperous future were dashed by the Macías Nguema regime; the deplorable attitudes of Spain during colonial rule had a psychological impact on Macías, one that helps to explain his demented behavior once in power.

As political scholar Samuel Decalo writes in The Journal of Modern African Studies, Macías was “regarded as introverted and not especially intelligent” by many and, as such, he

developed a sense of inferiority vis-à-vis foreigners, and especially those with a modern education…. His disdain for intellectuals, science and technology, as well as his purges of the entire educated class of the country, are at least in part traceable to this unease in a world in which he had always felt threatened. His ban of all modern drugs—allowing an entire island to be devastated by a cholera epidemic—his shift of the Guinean economy towards barter and autarky, were further symptoms of his “back to nature” drive, a return to the idealised, uncomplicated, pre-colonial life in which he felt most comfortable.

Believed by locals to be a powerful sorcerer, Macías kept a collection of human skulls and, as his insanity deepened, he took the entire national treasury with him to a remote hut where he would sit alone, communing with the spirits of those he had had killed.

More to Explore

Luanda, Angola: The Paradox of Plenty

The end came in 1979 with a coup led by Macías’s nephew, Teodoro Obiang Nguema. Writing just weeks after Macías’s trial and execution, Simon Baynham described the horror to which the small nation had fallen prey under the dictator.

A former detainee at Blabich, the nation’s most notorious jail, “one of the very few fortunate enough to survive,” Baynham notes,

reported that during his four years in prison from 1971 to 1975, he counted 157 prisoners beaten to death with metal rods outside his cell. Some of the victims were hanged publicly to the strains of Mary Hopkins singing, “Those were the days.” In 1977 the populations of two villages…were slaughtered by troops following a confrontation between soldiers and local people in which two soldiers had been killed. […] It is to be hoped that this former Spanish colony will never again be dubbed “Africa’s Concentration Camp.”

But even that hope has had it doubters. Teodoro Obiang is still in power today, making him the longest-serving leader in Africa. He’s been described by human rights organizations as one of the continent’s most brutal dictators. But, unlike his late uncle, Obiang has the benefit of oil to keep him in power. Discovered off the nation’s coastline in 1995, the black gold has emboldened Obiang to do whatever it takes to cement his iron grip on power, as Geoffrey Wood illustrates in his analysis of Equatorial Guinea’s political economy.

Weekly Newsletter

“Obiang won 97 percent of the vote in the 1996 presidential elections,” Wood writes, “a performance that was repeated in those of December 2002,” in part because the opposition candidate withdrew the day before the election, “citing threats of violence.”

Though Obiang claimed to support secret-ballot elections,

in many locales voting took place in public. In others, ballots were opened and ruling party officials voted on behalf of others with impunity. Opposition parties continue to boycott the House of People’s Representatives owing to commonplace electoral irregularities, the latter including an inflation of population estimates—from an estimated 500,000 to over one million—in order to facilitate ballot stuffing.

To the surprise of nobody, Obiang declared his son, Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the new vice-president in 2016. Only North Korea can seriously rival Equatorial Guinea for its ability to keep absolute power in the hands of just one, terrifying and, still, mostly unchallenged, family firm.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.