The words were etched in four languages, scratched into the edge of the pale wood by at least a dozen different hands, perhaps over the course of decades. When researchers translated and contextualized the overlapping text—faded in some spots, deliberately scratched out in others—they discovered messages of pride and dismissal, hope and despair, deep musings and passing thoughts shared in poetic verse, lyrics, symbols, and now-indecipherable allusions. If the slender board had been 2,000 years old, the find might have been a Rosetta Stone, celebrated as the key to unlocking the stories of long-disappeared cultures. But in the stacks of the Alderman Library on the campus of the University of Virginia, the pencil and ink on the carrel shelf looked like nothing more than meaningless graffiti to almost everyone—except Professor Lise Dobrin and her students.

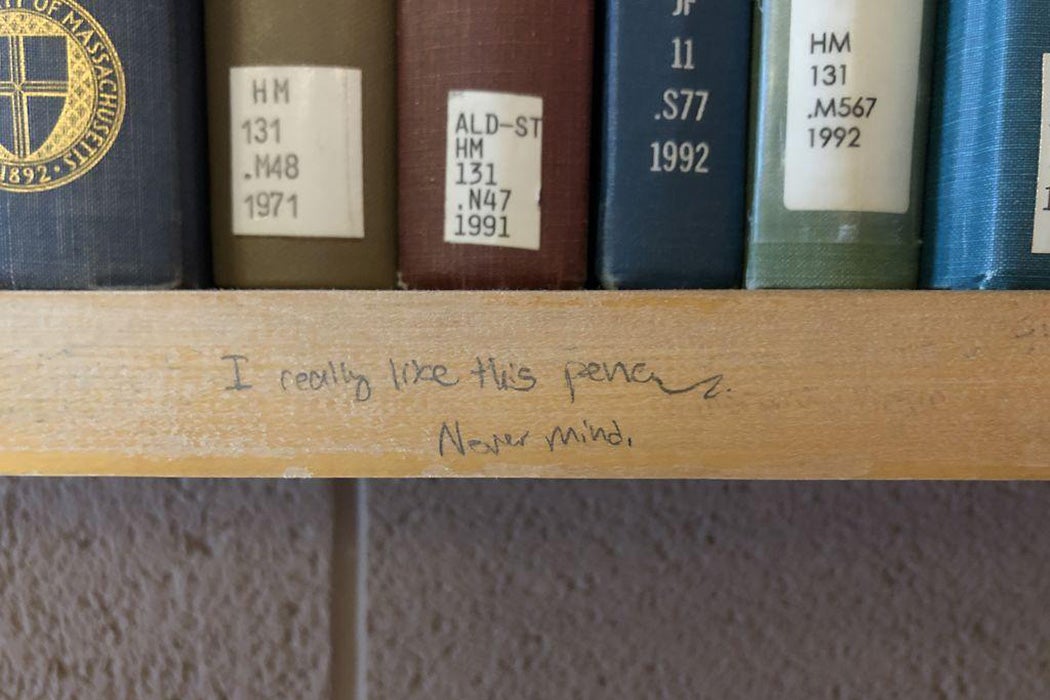

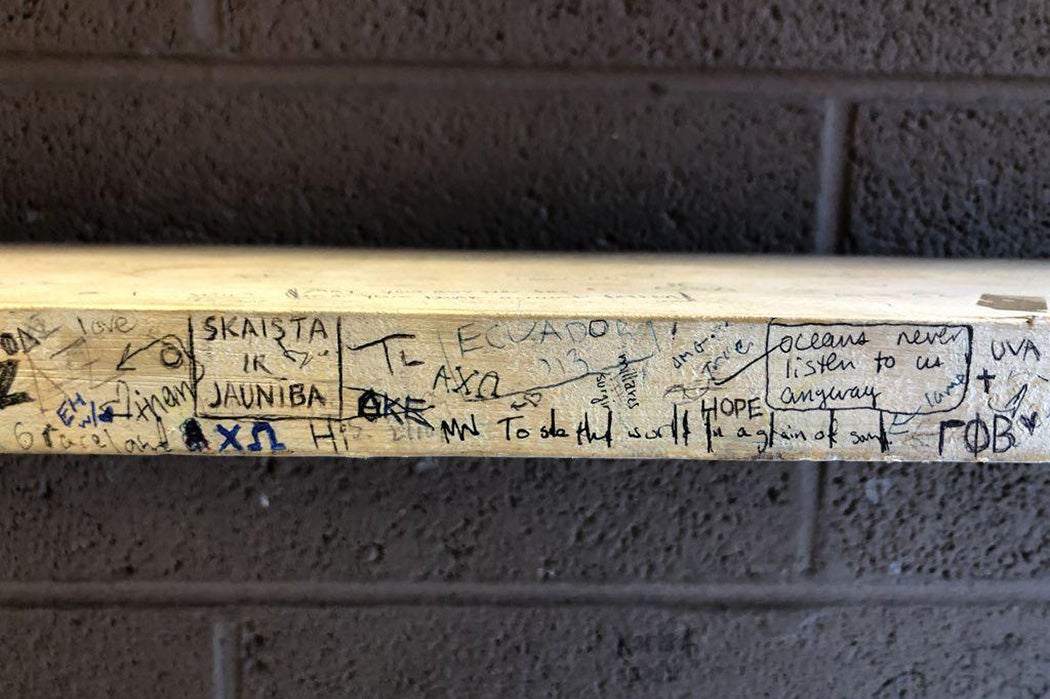

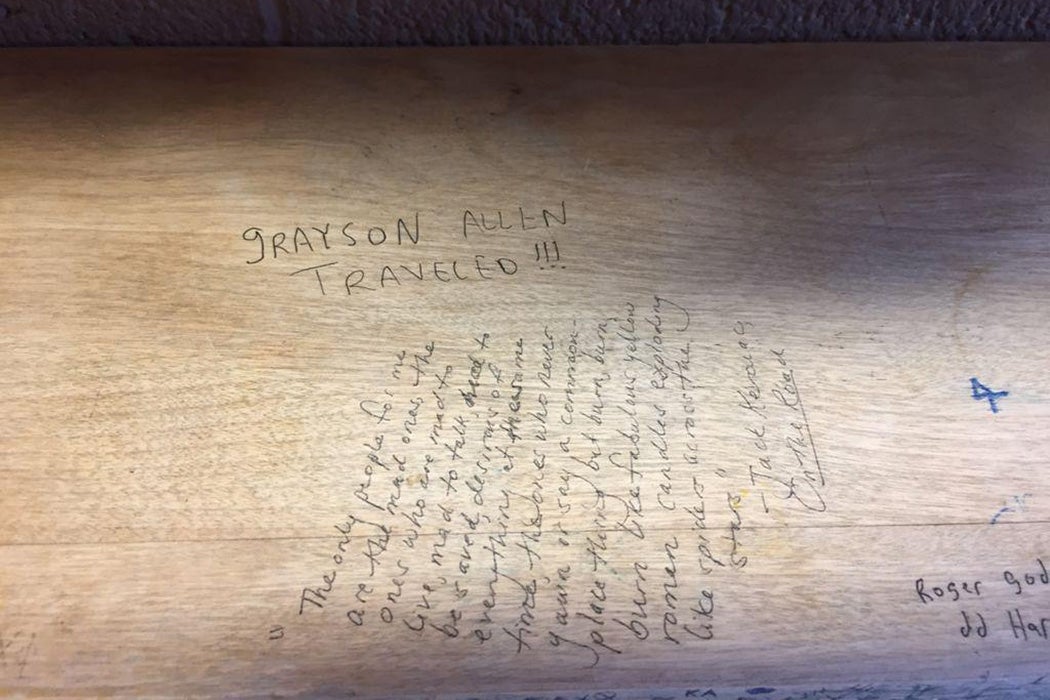

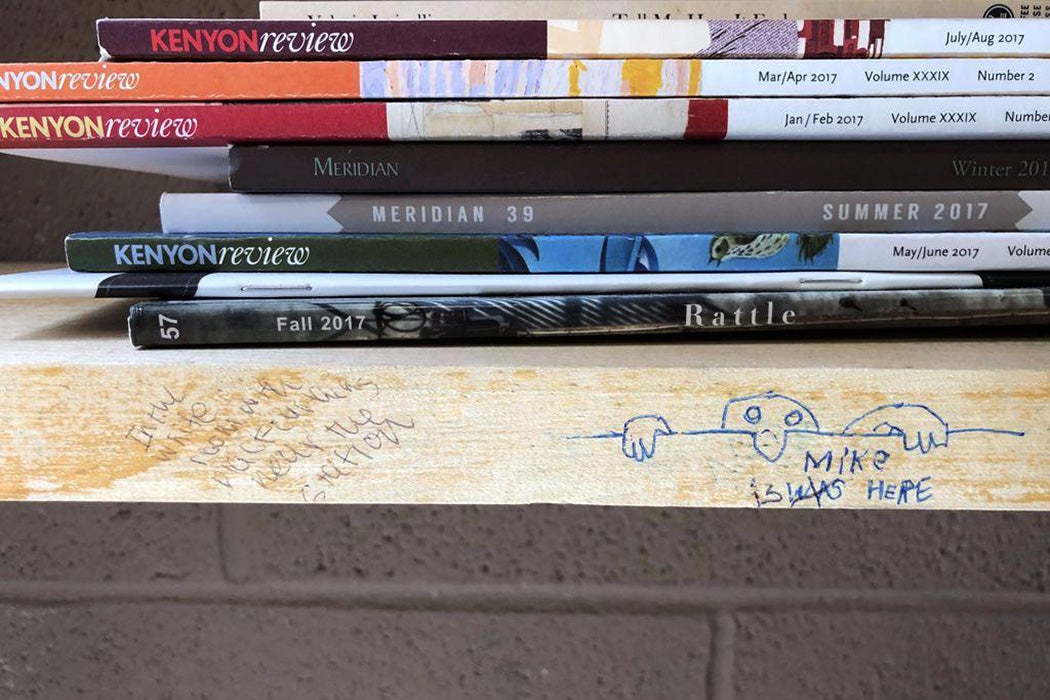

In the spring of 2019, the budding anthropologists of Dobrin’s Literacy and Orality course began to document the graffiti that had collected on the 176 study carrels in the nine-story Alderman Library “New Stacks” since the building’s construction in 1967. The idle doodles and stray observations inked onto the peg boards, painted concrete, and stained wood furniture were destroyed when the building was demolished in the summer of 2020 to make way for a new library. But those messages live on in a collection of nearly 2,500 student photographs shared by the University of Virginia via JSTOR, with a caveat: graffiti isn’t always polite and can be downright racist, misogynistic, and homophobic. (The students took seriously anthropologists’ responsibility to capture the world as it is, not as they wished it would be; personally identifiable information is edited out.)

Though the undertaking might seem absurd even to some who decorated the New Stacks, the students were contributing to a serious field of research dating back to the mid-1800s, when the word “graffiti”—derived from the Italian word for “something scratched”—was coined by archeologists to describe the markings found on ancient structures. Perhaps the best studied of these are the buildings of Pompeii where, researchers have concluded, graffiti was considered a respected form of writing. More than 11,000 wall inscriptions have been documented in the excavated portions of the city, many inside its grandest homes.

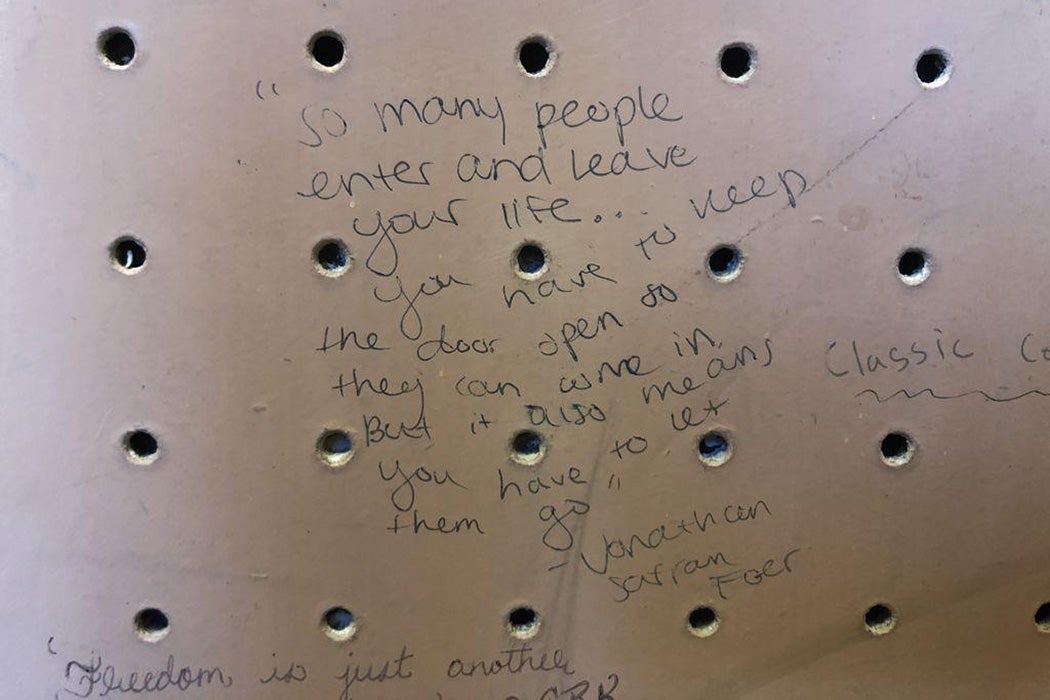

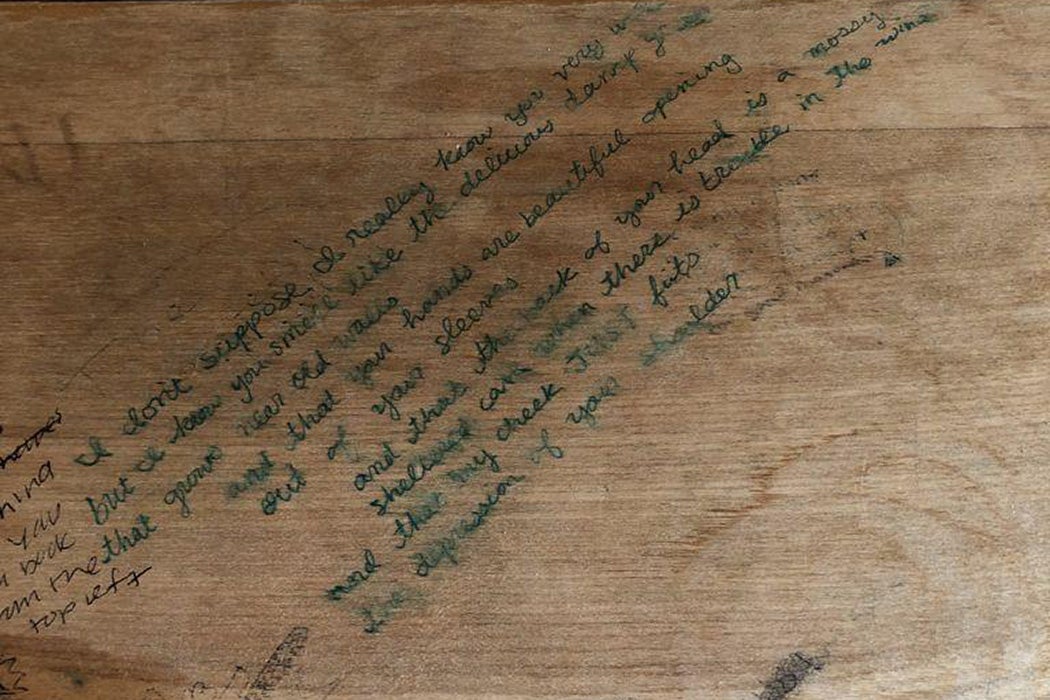

Social and cultural historian Rebecca R. Benefiel, who studied the words and pictures scrawled in Pompeii’s House of Maius Castricius, writes that graffiti is “a dialogue” and that those conversations—between different authors, between their text and their images, and between the messages and their location—are a “window” into aspects of the past that we might otherwise overlook. The students of UVA found the same, writing in a blog post, that the graffiti in the library carrels “reveals conversations playing out in slow motion between otherwise isolated crammers. It voices the anxieties and aspirations of contemporary college students striving to leave their mark on a large and sometimes impersonal institution.”

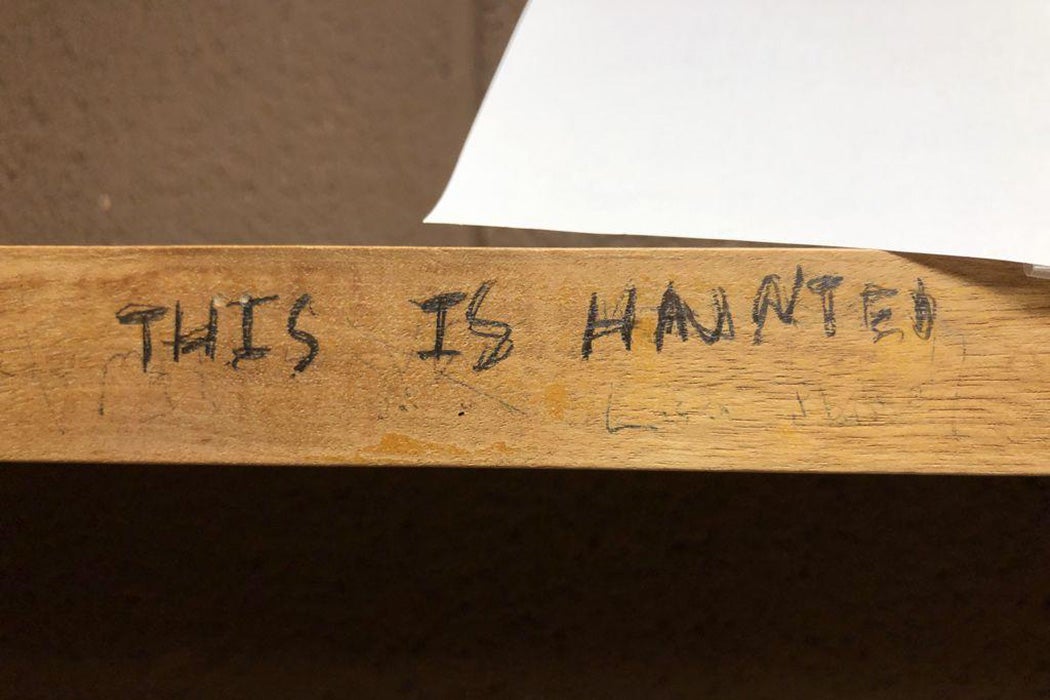

“Grades are nothing but ink on paper,” one person printed on the north wall of carrel 1M-1. “True,” added another in a loopy cursive. (Someone else in that same cubicle was worried about something even more menacing than GPA, repeatedly tracing over the words “THIS IS HAUNTED” on the upper shelf.) Advice for the academically anxious students could be found in the next carrel: “REMEMBER 2 STUDY YOUR PASSION” “I’m tired of thinking,” retorted a writer in carrel 4-10, quoting poet Li-Young Lee, “I long to taste the word with a kiss.”

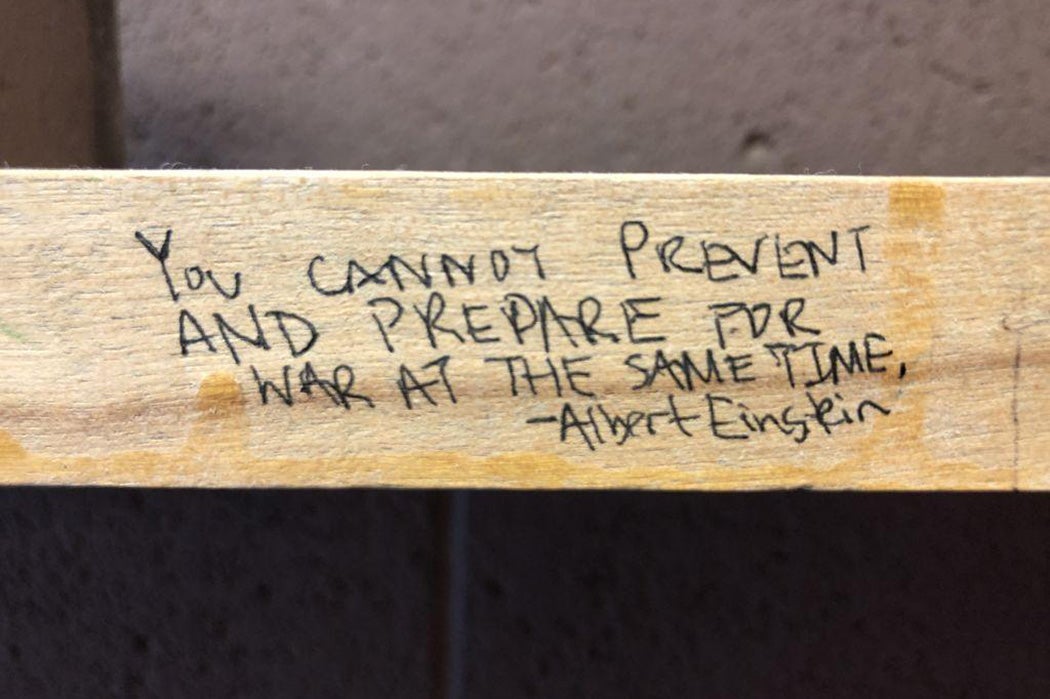

The words of countless other writers and thinkers, among them Albert Einstein, Jack Kerouac, Jonathan Safran Foer, and Zelda Fitzgerald, adorn the walls and shelves, as does what the student researchers believe to be an original verse: “each laugh a flower by my grave / each grin a battering ram at my door / though the walls under siege are mine to save / I think I’d be happier being yours.”

Graffitists from the class of 1927 to the class of 2021 left behind all the things you would expect: declarations of love and of hate, odes to sex, drugs and alcohol, anonymous confessions, and sketches of the WWII-era meme Kilroy (“Mike was here”). And they left behind a lot of things you wouldn’t expect: movie reviews, weather reports, even a pressing question that has vexed physicists and philosophers—“are electrons even real?”

On the southwest wall of carrel 4-17, in neat penciled letters, the student anthropologists found a plea that could have been directed to them: “Save the Stacks!” And in more than one way, they did. UVA’s new Edgar Shannon Library opened in January 2024 with pristine carrels but Dean of Libraries John Unsworth promised some of the students involved in the graffiti documentation project that he had no plans to prevent the next generations of students from leaving their own marks. “I’d rather have people writing on the walls than in the books,” he said.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.