As technology has evolved, so too have the different ways ideas may be expressed. Whereas a book or an article once took the form of a series of pages of text bound together, now digital monographs might include audio clips, video, data visualizations, and more. While innovative and exciting, these changes also present new challenges when it comes to preserving content in myriad forms.

That’s where Portico comes in. An initiative from ITHAKA, Portico offers digital preservation services; it works with nearly 1,300 libraries and more than 1,200 publishers to safeguard digital archives, many of which hail from underrepresented communities. Portico recently joined forces with colleagues from the libraries at New York University and the University of Michigan as well as from CLOCKSS, a digital archive akin to Portico, to create and release Guidelines for Preservability in New Forms of Scholarship. The guidelines, as well as a self-assessment tool that enables publishers to determine how to embed preservability in new scholarship, were funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Jonathan Greenberg, the digital scholarly publishing specialist at NYU libraries, led this initiative with his colleague David Millman, NYU Libraries’ chief information officer. Greenberg spoke with JSTOR Daily about the project’s parameters and goals.

JSTOR Daily: Can you talk a little bit about the genesis of this undertaking?

Greenberg: Mellon gave a round of grants starting in 2015 for the development of an ecosystem of digital publishing, and NYU was in that first group of grantees. After about four years, we recognized the need to start thinking more in depth about preservation. The University of Minnesota Press and CUNY Graduate Center had been building Manifold, University of Michigan Publishing had been building Fulcrum, and other platforms were underway and doing interesting stuff, but as publishers published more complex digital work, they ran up against the limits of the existing digital preservation infrastructure.

And so we, along with Portico and a number of other partners, initiated a project, Enhancing Services to Preserve New Forms of Scholarship, which aimed to improve services that already exist at places like Portico and CLOCKSS so that they could accommodate publications that had embedded multimedia, or publications that were websites and not conventional narrative.

We realized early on in that project that there were things that publishers could be doing, that scholars could be doing, upstream of the preservation process that could make a big difference.

What kind of things?

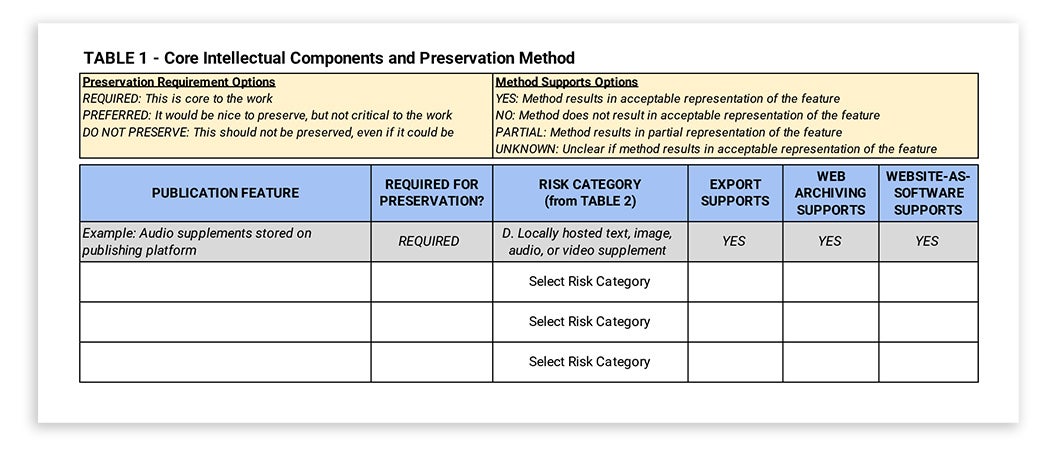

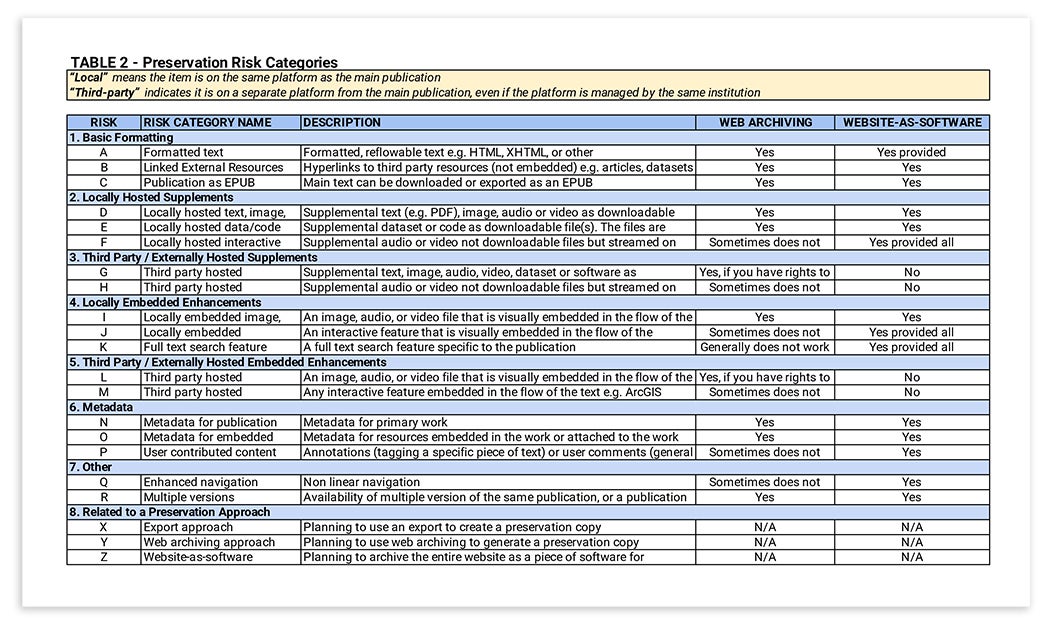

Out of that first project came guidelines that we’ve now revised, and those guidelines are best practices for how you use platforms, how you choose platforms for publishing, how you might use audiovisual materials in publications; things like defining the core intellectual components of your publication so that when you get to the stage where you’re thinking about preservation, you know what it is that you need to be preserved.

Our hope was that publishers, scholars, and platforms would see the guidelines and be able to act before the publication was out the door, and before it got to a place like Portico or CLOCKSS. We also realized that our guidelines were hefty and complicated for many publishers. Many of these things are technical points that an editor at a university press might not understand. There were originally sixty-eight guidelines. There are now seventy-two. It’s a lot, and so through the Embedding Preservability in New Forms of Scholarship project, which is the follow-up, we got the sense that a lot of publishers who need this, needed a way to guide them through the guidelines. So, we developed a self-assessment tool.

How was the tool developed?

The project centered on an embedding process where we would meet with publishers over the course of the publication process. We had questions that we asked—all recorded in a shared document—and we’d follow up at key points in the publication process and give specific advice. The process worked well, but this is a grant-funded project—we’re not there in perpetuity, and we could only embed with a handful of publishers to begin with.

So, we decided to create a self-assessment tool as a way to approximate our embedding process. We conducted workshops at which participants used the self-assessment tool, and we continued to refine the tool as we learned from those workshops. The tool guides publishers or others involved in creating digital scholarship through this four-step process.

Do guidelines rely on the idea that in addition to editing a manuscript, editors must undertake this self-assessment? How is a medium-sized or a small university press, with limited resources, supposed to move through this self-assessment?

We imagine that this is useful beyond university presses, that there are many types of publishers throughout the whole ecosystem—whether they’re scientific publishers, publishing articles that have data visualizations in them, whether they’re digital humanists building work on their own— there are a wide range of people who might find this useful.

It’s important to realize that there aren’t many university presses doing this kind of complex work. And in order to create digital monographs that do have multimedia in them or have aspects that rise above what a conventional monograph has, you need the staff and the workflows to support that.

What kinds digital of monographs do you foresee needing this kind of self-assessment for preservation? Are these specifically for, say, art history texts?

I’ll make a distinction here between publications that we worked with on one hand, and on the other hand, the kinds of publications that this would be useful for.

What we worked with was very much determined by the publishers that we were working with, what their lists are, and what they do. We had an ethnography of immigrant students in school, Knowing Silence, which uses recordings of those students as part of the text. There’s a lot of multimedia work done in archaeology, and University of Michigan Press has, as part of its list, a foot in the world of archaeology. We had another book from University of Michigan Press on hip hop, Owning My Masters (Mastered) that consists of audio tracks and liner notes. We worked with a journal from the American Psychological Association called Technology, Mind, and Behavior which includes interactive digital features.

More to Explore

Preserving History at the Digital Transgender Archive with Portico

As we talked to people at conferences, we saw more fields that could benefit from our work. We were at a Society for Scholarly Publishing conference last year and met people working on biomedical journals, and they saw this as something that could be useful in training people who prepare data and data visualizations for publication. In that field, there are jobs that exist just for that. Media studies is another field that really comes to mind that has a long history of digital publication that uses audiovisual material and other digital tools.

To what extent does this kind of self-assessment tool and these guidelines influence—if at all—how scholars think about their scholarship and how they express it? Whereas before somebody might have said, “You know, I’m just going to write this monograph, and it’ll get published and that’s great” are people now conceiving of projects in entirely different ways because of technological advances and multimedia opportunities?

Hard to say. I don’t know that the work that we’ve done is going to get scholars thinking about complex digital publishing pathways, but what I hope is that scholars who are involved in this work start to think sooner about what they’re doing.

There are a lot of parallels to accessibility. Accessibility has found a foothold in scholarly communications the world over during the past ten years in no small part because of laws mandating it. If every publisher asks you to write text alternatives for all images for the benefit of sight-impaired readers, and you realize they’re always going to ask that, then you might start to write them yourself as part of your writing process. We’re seeing that creators of scholarly content are slowly incorporating practices that lead to accessibility in their workflows. In fact, some libraries and universities are proactively reaching out to graduate students and to scholars to imbue these practices.

I would hope that a similar thing could happen with preservability, maybe even alongside accessibility, because some of the techniques and best practices that we identify overlap significantly with practices for accessibility.

How do you counsel publishers who are keeping in mind digital preservation efforts, given that new technologies are always emerging and digital platforms may become obsolete. How do you preserve something if the means to view or experience it may change altogether?

Well, that gets at the heart of what preservability is. In general, I would say that the more preservable something is, the less dependent it is on its platform.

There are various techniques to preserving content, whether you’re using web archiving, in which case you get a file that contains the whole website, or the more conventional, export-based preservation where you extract files hopefully in file types that are recognized as standard or easily preservable. You package them up in a way that connects them all clearly for somebody in the future so that they would know how all the files fit together.

In the case of complex work, you might package up a whole piece of software or a website that that has dynamic elements as software, so that somebody in the future could emulate that. But in all of those cases, the platform doesn’t need to be around—we don’t need it to replay a web archive. If we’re successfully able to archive the website, then we’re confident we’ll be able to replay that.

The web will change, and there will be risks that we can’t anticipate; nobody’s promising that these things will be able to be replayed 50 or 100 years in the future, but I think what we’re doing is the most that we can to assure long-term access.

What was Portico’s role in all of this?

Portico’s absolutely vital to the whole initiative. Portico and CLOCKSS serve outsized roles in preserving digital scholarship in our world. They were essential partners to have when we’re talking about enhancing preservation services.

There have been efforts within Portico to create infrastructure, to create workflows for more complex digital articles and books that came in. Our turn toward content creators and going upstream was kind of an admission that the biggest difference we’re going make in terms of preservation of this work is not with the preservation services themselves, but if we can bring work that is already more preservable. For services like Portico that really have to operate at scale, it’s really important that we start to think about how publishers and scholars can make their work more preservable.

What are the next steps?

I’d like to talk next steps, but before I do, I want to mention another point that has come up very frequently for me over the course of these projects, which is that one of the complicated things about preservability is that it’s not always clear what the goals might be or what success might mean. I think this is true in preservation more broadly, but especially when we’re dealing with complex, sometimes cutting-edge digital work. In terms of making things more preservable, our work will always be imperfect to a degree, and one of the reasons for that is that preservability is not the only value that publishers and scholars have in mind when they’re creating these works.

If you’re doing something truly cutting edge, then you’re likely going to be sacrificing some preservability to do that, and that’s sometimes a really good choice to make. There are real limitations in terms of resources to preservability, in terms of what kinds of resources publishers and scholars might have to use, in terms of technology.

Weekly Newsletter

Finally, I think it’s important to come back to the reality that preservation may also not be of value to everyone for every piece of scholarship. In fact, there may be some types of scholarship, where scholars really don’t want their work preserved; it’s seen as something ephemeral or that belongs to a particular community, perhaps. Those are certainly the exception, but all of that is just to say that over and over again, people raise the possibility of having a standard, like we have in accessibility. We have standards, such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), where sites can meet the A or AA standard, and these are international standards. I don’t even know if that’s possible with preservability because, you know, only a publisher and a creator really know what their goals are and what their values are and how important preservability is to their work.

It’s almost as if it’s an honor system, in that you’re the judge of the merits of the preservability of your product.

Absolutely. And if you take it outside of the realm of scholarship, and think about websites for a moment, then it becomes even clearer. For some websites, like government websites, it’s really important that they’re preservable. Other ones have very different goals, and it’s important to honor that.

So, about those next steps?

I’d like to see communities of publishers and scholars find ways to communicate the values and the idea of preservability within their communities. There’s a lot of work to do to simply get these concepts out there, and we have limited reach. We’ve reached a fair number of librarians and people within the university press world, and some people within the digital preservation world, but there are a lot of people creating scholarly content who aren’t really aware that this might be a challenge for them.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.