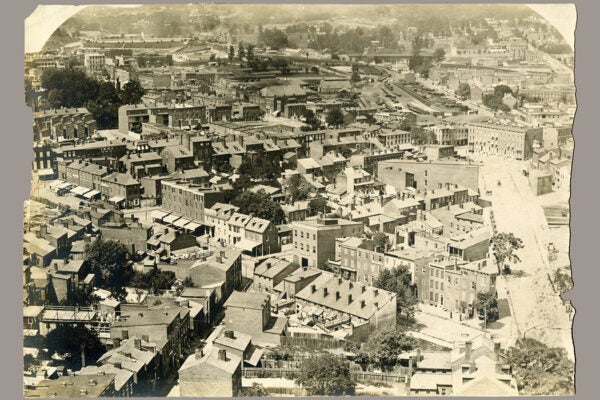

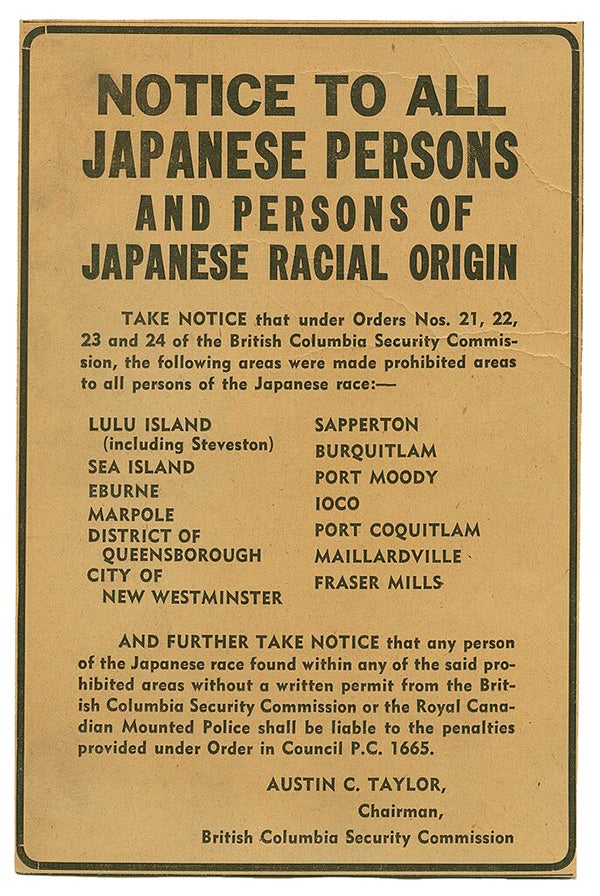

About 22,000 Japanese Canadians in British Columbia were interned during World War II. Categorized as security risks simply because they were of Japanese ancestry, most were British citizens of Canada and sixty percent were Canadian-born. The majority were sent to “interior housing centres” in Slocan Valley in eastern British Columbia, while several thousand able-bodied men were sent to road work camps or sugar beet farms. None were ever found guilty of disloyalty.

In some respects, this removal of Japanese Canadians paralleled the removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast following the Imperial Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. But unlike in the US, where most of the internment camps were closed by the end of 1945, Japanese Canadians were kept from returning to British Columbia until 1949. (After 1945, nearly 4,000 were forcibly deported to Japan; many of these would spend years trying to get back to their actual homeland.)

Scholars Jordan Stanger-Ross and Will Archibald, working with the Landscapes of Injustice Research Collective, examine the role of the individual charged with responsibility for all the property left behind after the removals.

The Vancouver office of the Custodian of Enemy Property, run by Glenn W. McPherson, was supposed to safeguard this property. Soon after the internment was ordered in late February 1942, McPherson started selling off what he defined as perishable assets: grocery stock, but also fishing vessels and automobiles.

In January of 1943, the Custodian’s mission was officially revised: now it was supposed to sell all the real estate and personal belongs of Japanese Canadians. The resulting funds could only be used by the interned to pay for their confinement.

“Japanese Canadians were to be disposed of all their property without their consent,” write the authors. “Many did not learn of the fate of their homes, farms, businesses, or belongings until it was too late: everything they owned had been sold, usually for prices far below [market rates].”

Glenn McPherson has usually been delegated to footnotes in the history of the internment. Historians have focused instead on role of Prime Minister Mackenzie King, Cabinet Minister Ian MacKenzie, and race-baiting politicians in British Columbia. It was, however, McPherson who “developed the logic to justify the forces sales, wrote the policy into law, and installed the administrative processes of sale.”

At the same time, McPherson also worked as a British Security Co-ordination (BSC) agent. Based in New York City, BSC was a hemisphere-wide British intelligence operation.

More to Explore

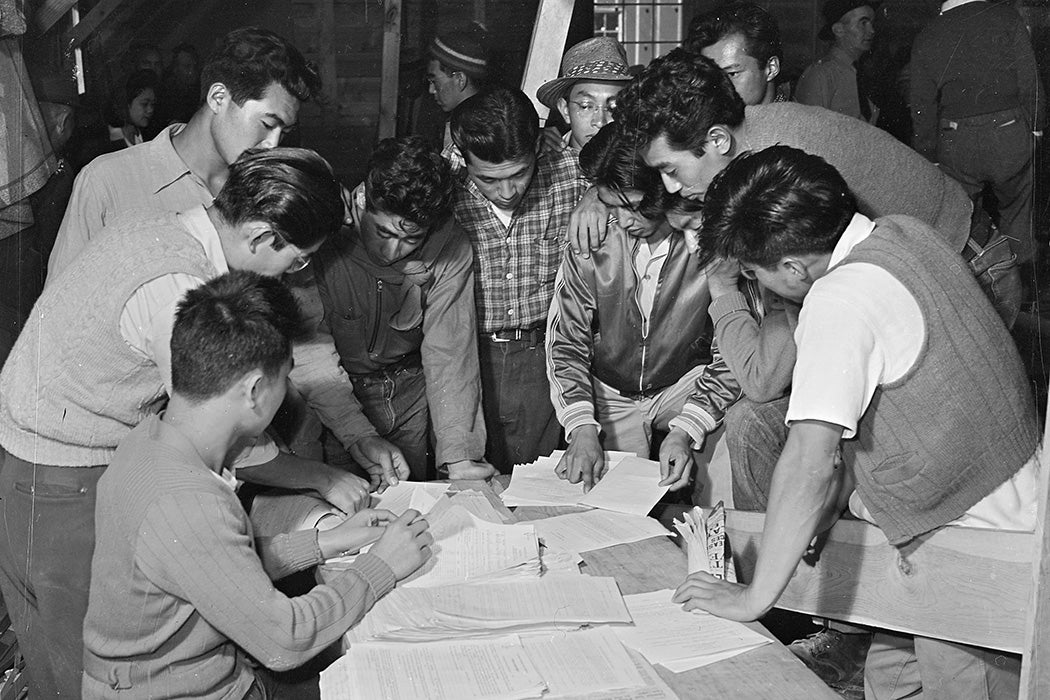

Draft Resistance in Japanese American Internment Camps

“In this role, [McPherson] authored secret and unsubstantiated claims against Japanese Canadians, both collectively and individually, arguing that they were indisposed, as a matter of racial character and fealty, to remain loyal to Canada. […] McPherson the secret agent reads very differently from the bureaucrat who crafted the logic of perishability to justify forced sale,” note the authors.

McPherson’s BSC reports “take on an almost pulpy quality, as if he were playing out his own person spy drama,” criticizing the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for ineffectually combating the “Jap” menace in British Columbia, all of it controlled by the “Mikado” in Tokyo. (The RCMP, the national police force, had no evidence of espionage or sabotage by the Japanese Canadian population.)

Mixing his bureaucratic and spy work, McPherson proved to be a most “unfaithful” custodian. Citing the real estate market and other factors, Stanger-Ross and Archibald write that “a government faithfully committed to the interests of the owners would have held these properties, not sold them.”

Weekly Newsletter

So in 1949, when Canada’s racist policy was finally abandoned, there were no homes, farms, or other assets for Japanese Canadians to return home to on coastal British Columbia. The “property belonging to Japanese Canadians became the ‘antiques’ and ‘inheritance’ of other Canadians.”

In 1988, soon after the US apologized for the internment of Japanese Americans, the Canadian government apologized for its war and post-war actions against Japanese Canadians. The settlement included a largely symbolic redress payment of $21,000 to survivors, as well as monies for a community fund and human rights projects to work to prevent such racist outrages in the future.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.