In 1905, as the vestiges of Victorian England gave way to an uncharted future, friends convened in a home in the Bloomsbury district of London to discuss art, philosophy, literature, politics, and love. They included painters, novelists, art critics, and political philosophers, many of whom became famous contributors to the modernist movement in literature and art. Among its most renowned figures were novelists Virginia Woolf and E. M. Forster; painters Vanessa Bell, Roger Fry, and Duncan Grant; nonfiction writers and critics Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, Desmond MacCarthy, and Leonard Woolf; and economist John Maynard Keynes.

Bloomsbury’s members believed that the individual’s experience and sensation—and not an exhaustive representation of material reality—ascribed art its value. Art critic Clive Bell criticized the reliance on “learned litanies of names and dates from the art historical canon, or particular political or moral templates,” according to scholar Christopher Reed, and insisted that what mattered most was if and how art made the viewer feel. Virginia Woolf’s stream-of-consciousness style and the group’s interest in psychology and Freudian theory reflect this focus on interiority. Like their modernist contemporaries, the members of Bloomsbury, argues David Sidorsky, “sought to emancipate literature and art from subservience to morality, especially from any commitment to Victorian ethical didacticism.” By innovating new aesthetic forms and philosophies, Bloomsbury relegated Victorianism to the realm of the “nonmodern.”

Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press, established in 1917, materially contributed to the creation of literary modernism. Originally conceived as a vehicle for publishing their own and their friends’ work, Hogarth eventually fostered an international network of literary exchange. The press published translations, feminist works, and other material that contributed to an alternative, distinctly modern literary history that moved beyond the traditional British canon.

Bloomsbury had no declared agenda, but its ethos was distinct. According to Noel Annan, a Bloomsbury contemporary, the group

had two fixed items of faith: (1) pleasure is a good […] and (2) a belief in humor (a corrective to taking oneself too seriously). They believed in a relativistic world. Courage is good, but so is sensitivity; seriousness is good, but so is frivolity; rationality is good, but so is imagination. They cherished an awareness of a multiform world—and a willingness to wonder at it and leave it alone.

The following reading list offers an introduction to the breadth of ideas the group engaged and popularized.

Kurt W. Back, “Clapham to Bloomsbury: Life Course Analysis of an Intellectual Aristocracy,” Biography 5, No. 1 (Winter 1982): 38–52.

The Bloomsbury Group, according to Back, “assumed intellectual eminence as a birthright analogous to an aristocracy.” This assumption stemmed from its inclusion in a lineage of English intellectuals with roots among the Clapham Saints. This small Evangelical group comprised merchants who lived in London during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and achieved a comfortable income despite having “grown up on the margins of both political power and economic development.” Back construes the evolution of Clapham into Bloomsbury on the model of an aristocratic family lineage. Bloomsbury’s intellectual ancestors created a text that Bloomsbury could accept, reject, or misread, but could not ignore. Despite seismic cultural and societal transformations, the changes in outlooks between generations became, in part, an “intrafamilial reaction.” According to Back, this intellectual aristocracy persisted until the dilution of Bloomsbury by new members from outside the family lineage. In a compelling analogy, Back asserts that Bloomsbury was not wholly new but rather a modern iteration of an existing elite with a long history: “one can say that the genotype […] was preserved, while different conditions in the social environment led to a variety of phenotypes.”

Quentin Bell, “Bloomsbury and the ‘Vulgar Passions’,” Critical Inquiry 6, No. 2 (Winter 1979): 239–256.

Quentin Bell was an art historian and writer. He was also the son of Clive and Vanessa Bell and the nephew of Virginia Woolf. In examining Bloomsbury’s politics, Bell contextualizes and explores the group members’ evolving positions throughout the twentieth century. Bell refuses to collapse them into one homogeneous cohort. Still, he asserts that they shared a common attitude which eschewed the “unreasoning emotions” that led many of their contemporaries to adopt “the religion of war.” Bloomsbury included pacifists, conscientious objectors, soldiers, and agents of empire. But each figure enacted the “Bloomsbury habit of rational thought combined with moral purpose.” According to Bell, Bloomsbury did not subscribe to unexamined values of any kind, including nationalism, imperialism, homophobia, and misogyny. Because men seeking power “rely upon feelings rather than the intelligence of the masses” to achieve their own (often militaristic and authoritarian) ends, the intervention of rational thought into these “vulgar passions” was, for Bloomsbury, a form of political resistance. Bloomsbury, Bell says, “had no use either for the hero or for the saint. In its polemics it appeals to good sense and good feeling and relies upon the belief that ultimately the reasoned argument will prevail.”

Sara Blair, “Local Modernity, Global Modernism: Bloomsbury and the Places of the Literary,” ELH 71, No. 3 (Fall 2004): 813–838.

While “Bloomsbury” names the group of artists, writers, and intellectuals who met regularly to discuss art, literature, and philosophy, it’s also the name of a place. In this deeply researched article, Blair seeks to “re-place” it. “Bloomsbury’s embeddedness within Bloomsbury,” Blair argues, “is what leads it to become […] global in its resonances, a site of cultural contact and contestation where both canonical high modernisms and an emergent anticolonial modernism take shape.” By examining the networks of conversation, contact, and exchange that occurred in Bloomsbury, Blair shows that modernism was a “contact zone, in which matters of consciousness are visibly inseparable from class conflict, the imperatives of nationalism, the dynamics of colonial self-recognition.” In so doing, Blair replaces the “aura” that clings to the Bloomsbury Group with a more nuanced picture of a group of artists living and working within a transitional place and time, deeply influenced by the imperial dynamics that gave shape to their lives and their nation.

Robert Murray Davis, “Bloomsbury: And After?” South Central Review, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Summer, 1986), pp. 69–77.

In this incisive and entertaining exploration of English writers of the 1930s, Davis argues that those writing after Bloomsbury lacked a “common object or program to unify them.” Not only did these writers—including Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, Anthony Powell, and Henry Green—lack the private incomes common to Bloomsbury, they were also dispersed across the globe. For them, unlike for Bloomsbury, “there was no unity of place” and “little unity of action.” Davis analyzes the two eras’ literary depictions of dinner parties to illuminate the contrast between their worldviews: “For the novelists of the 1930s, the dinner table was also a miniature society and world, but a world where […] there is structure, but no harmony; light, but no illumination; friction, but no warmth.” By contrast, “Bloomsbury was conceived in an age of […] the secular humanist’s faith that by the effort of man’s imagination, intellect, and good will, all could be made well.”

Suzanne Henig, “The Bloomsbury Group and Non-western Literature,” Journal of South Asian Literature 10, No. 1 (Fall 1974): 73–82.

One of the oft-cited generalizations about modernist expression is that modernist writers and artists were fascinated by non-Western literature and culture. T. S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land (1922) is typically seen as proof: it includes Sanskrit phrases and references to the Bhagavad Gita. According to Henig, however, in its early years, the Bloomsbury Group was uninterested in non-Western literature. That changed and eventually Bloomsbury members exhibited an interest in works from Japan, India, and other Asian countries. Henig argues that while Bloomsbury cannot be credited alone with popularizing non-Western literature, members of the group did make concrete contributions to this phenomenon. These include the translation of non-Western works, including the use of non-Western literary elements in their work; the publication and support of unknown non-Western writers; and the group’s impact on younger writers. For Henig, writing in 1974, Bloomsbury’s contributions “are in part responsible for the resurgent interest of the English-speaking world today in Asian literature.”

Simon Joyce, “On or about 1901: The Bloomsbury Group Looks Back at the Victorians,” Victorian Studies 46, No. 4 (Summer 2004): 631–654.

Bloomsbury’s view of the past and modernity’s relationship to it “set the terms for thinking about the nineteenth century in the twentieth.” A truism exists within literary studies that Bloomsbury engaged in a wholesale rejection of what it perceived as the Victorian era’s moral didacticism and aesthetic materialism. According to Joyce, however, this truism depicts both Bloomsbury and the Victorians as monoliths and prevents a nuanced understanding of the complex ways Bloomsbury engaged with its Victorian past. Lytton Strachey, a Bloomsbury writer and critic, published Eminent Victorians, a series of case studies of influential Victorian figures. Though Strachey’s work purports to be a takedown of Victorians’ pretensions of moral superiority and a rejection of Bloomsbury’s literary forebears, Joyce argues that the text reveals that the nineteenth century is “necessarily and definitively self-divided.” This flies in the face of what Joyce calls Bloomsbury modernism, “which preferred to define the past as stolid and one-dimensional and the present alone as marked by complex ambiguities.”

Harry Levin, “What Was Modernism?,” The Massachusetts Review 1, No. 4 (Summer 1960): 609–630.

Modernism, like all aesthetic movements, “fits in with a dialectical pattern of revolution and alternating reaction, as the breaking of outmoded images gives way to the making of fresh ones.” Writing in 1960, Levin observes that modernism’s experimental forms had become “traditional” in the sense of having been fully integrated into the literary canon. Levin then specifies the (once revolutionary) attributes of literary modernism as it appeared in the works of Bloomsbury members and their contemporaries. Levin names the following hallmarks of modernism: the creator’s “paradoxical state of feeling belated and up-to-date simultaneously”; an international and urban sensibility; a preoccupation with myth; an engagement with psychology, and particularly with Freud’s ideas; and a focus on impressions and sensations, manifested in stream-of-consciousness prose. Levin argues that these manifestations of modernism are associated with more than one “annus mirabilis,” or marvelous year, of modernist creation; scholars often point to 1910, 1922, and 1924. In elucidating these writers’ stylistic and intellectual choices, Levin created a “bulleted list” of modernist writing’s characteristics that served as the backdrop for scholarly discussions of modernism for decades.

Ruth Livesey, “Socialism in Bloomsbury: Virginia Woolf and the Political Aesthetics of the 1880s,” The Yearbook of English Studies 37, No. 1 (2007): 126–144.

Like many scholars included in this list, Livesey is interested in the relationship of Bloomsbury’s politics and aesthetics to those of its Victorian predecessors. For her part, Livesey focuses on how the socialism espoused by George Bernard Shaw and his fellow Edwardians (as Virginia Woolf dubbed Shaw and his contemporaries) modulates into a “politics in which desire for the beautiful and the affect of poetry was part of the process of social change.” Bloomsbury, Livesey asserts, based its moral conscience on aesthetic sensitivity, not solidarity with the working class. The “sympathy of the heart and nerves” that characterized didactic Edwardian novels no longer functioned alongside the “aesthetic sympathy of the artist’s imagination in the modern era.” It was on the basis of their “individualizing autonomous aesthetics” that Shaw held Bloomsbury responsible for abandoning the collective cultural engagement that characterized his earlier socialist era.

More to Explore

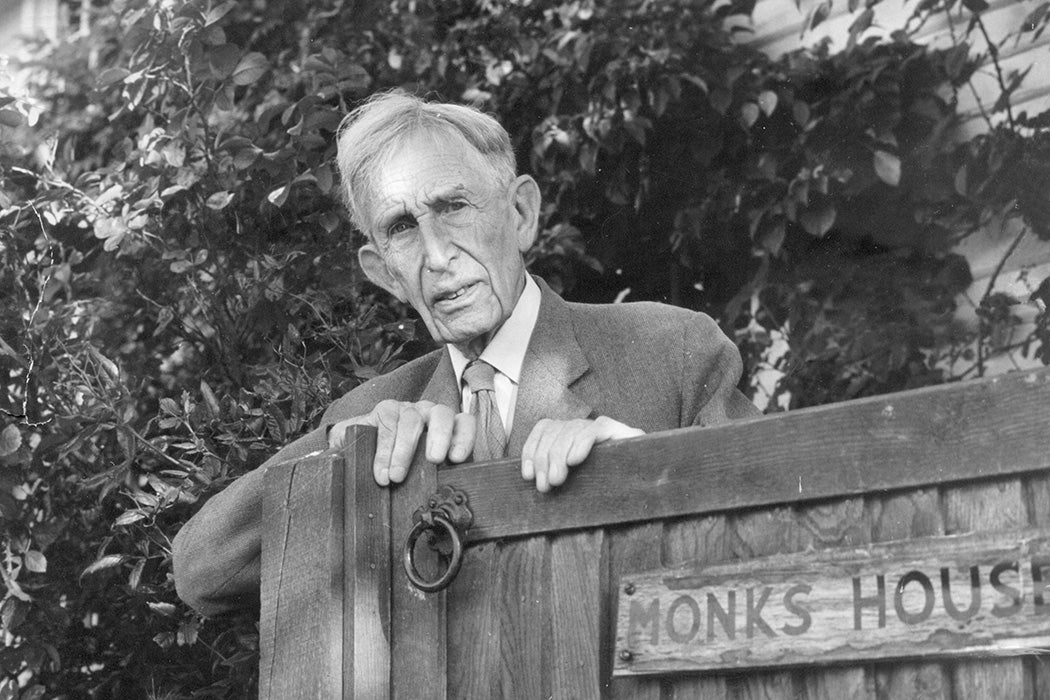

How Leonard Woolf Critiqued Bloomsbury from Within

Christopher Reed, “Art Words,” Woolf Studies Annual 29 (2023): 162–166.

Bloomsbury’s art critics Clive Bell and Roger Fry popularized the term “Post-Impressionism.” They initially used the concept to bring together a disparate group of continental European artists in the 1910 exhibition “Manet and the Post-Impressionists” at London’s Grafton Galleries. This exhibition is widely seen as the inauguration of modernism in the visual arts in England. Reed, an art historian, focuses on another of Bell’s “art words”: “Post-Impressionist-Unanimist-Neo-Individualist”. While Post-Impressionism connotes a “newness positioned as part of a teleology of western stylistic development,” Bell’s other two terms “point to unresolved tensions at the heart of modernist aesthetics.” This tension lies in the relationship of the individual artist’s innovation to collectivity and tradition. Modernist writers, argues Reed, were preoccupied with this unresolvable tension. It’s reflected in the notion of “Unity–Dispersity” that haunts Virginia Woolf’s late novel Between the Acts (1941). For Reed, Bell’s string of art terms “evoked aspirations for a modern art that could proffer forms of collaboration and community along with new conceptions of individual personhood.”

Christopher Reed, “Through Formalism: Feminism and Virginia Woolf’s Relation to Bloomsbury Aesthetics,” Twentieth Century Literature 38, No. 1 (Spring 1992): 20–43.

According to Reed, Roger Fry and Clive Bell opened the way for the creation and reception of modern art in the first decades of the twentieth century. Their criticism and fellow Group members’ literary and visual art rejected mimesis “in favor of concentration on the play of abstract form.” Bloomsbury’s conception of formalism evolved, eventually landing on an aesthetic that attempted to “reintegrate representation into the formalist paradigm, without sacrificing an ideal of purely aesthetic experience.” Virginia Woolf’s novels illustrate this claim: while the conspicuous rejection of formalism characterizes her early fiction, she later appreciates formalism’s potential feminist application. Because formalism disrupts patriarchal assumptions about the nature of aesthetic experience (namely, that the author possesses omniscient knowledge transferable to the reader), Woolf deploys it to depict the impressions and sensations that characterize the female experience. In the end, Reed argues, “what finally undermined Woolf’s allegiance to formalism concerned its insistence on the aesthetic as a realm completely apart from other experience.”

S. P. Rosenbaum, “Preface to a Literary History of the Bloomsbury Group,” New Literary History 12, No. 2 (Winter 1981): 329–344.

The very existence of the Bloomsbury Group, says Rosenbaum, “has been questioned, almost since its inception and sometimes by the members themselves.” However, Rosenbaum argues, a profusion of biographies and publications focused on Bloomsbury since the 1960s is proof of ongoing curiosity about the phenomenon and the people involved in it. By establishing a chronology of the Group members’ works and analyzing the interrelationships of ideas therein, Rosenbaum seeks to create a literary history of Bloomsbury. In so doing, he concludes that Bloomsbury’s writing combines two broadly different “clusters of value.” One is liberal; the members’ work reflected belief in “egalitarianism, individualism, toleration, pluralism, secularism, truth, reason, and analysis.” The second is visionary: Bloomsbury shared “a profound faith in love, art, beauty, ideality, imagination, intuition, synthesis, mysticism, and reverence.” These different types of values, Rosenbaum argues, complement each other in many of Bloomsbury’s most famous texts.

Anindyo Roy, “‘Telling Brutal Things’: Colonialism, Bloomsbury and the Crisis of Narration in Leonard Woolf’s ‘A Tale Told by Moonlight’,” Criticism 43, No. 2 (Spring 2001): 189–210.

Leonard Woolf’s legacy is that of a preeminent art critic and theorist. He was also a fiction writer, but his books and stories are not often studied. Roy, however, examines the fiction and letters Woolf composed when he was stationed in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) as a colonial magistrate at the outer periphery of the British empire. His story “A Tale Told by Moonlight” registers a crisis of narration that is, Roy argues, symptomatic of Woolf’s complicity in the project of empire. It features a complexly embedded plot and narrative dislocations. Roy asserts that the central narrative voice cannot retain its singular directionality; its persistent process of deferral “paradoxically shapes and undermines the narrative.” This style connects the violence of colonialism to the violence of representation and reveals Woolf’s awareness that he is implicated in the brutality of the entire colonial system. Roy argues that Woolf’s letters and his reiterative narrative style indicate that the writer “seems to have suspected that the Bloomsbury circle, despite its unorthodox views on representation, could not see beyond” the fictionality that masks the violence of their own civic and cultural identity, as produced by the brutality of colonialism.

Weekly Newsletter

David Sidorsky, “The Uses of the Philosophy of G. E. Moore in the Works of E. M. Forster,” New Literary History 38, No. 2 (Spring 2007): 245–271.

Most of the original male members of Bloomsbury were Cambridge Apostles, meaning they were members of a debating society that originated in the nineteenth century at Cambridge University. G. E. Moore was an Apostle. He was also a Cambridge faculty member and philosopher most widely known for his refutation of Idealism and an insistence on common sense as a philosophical method whose ideas strongly influenced the Bloomsbury circle. According to Sidorsky, “Bloomsbury derived from Moore a belief in the moral priorities of cultivating a sensitive sensibility, of analyzing reflectively one’s own state of mind, and of paying utmost attention to personal relations.” These beliefs are reflected in E. M. Forster’s novels and among members of the Bloomsbury Group, for whom moral sensitivity was acquired by the same methods as aesthetic sensibility: attunement and rigorous cross-examination.

Wilfred Stone, “Some Bloomsbury Interviews and Memories,” Twentieth Century Literature 43, No. 2 (Summer 1997): 177–195.

Wilfred Stone was a scholar of E. M. Forster’s work. He met with several members of the Bloomsbury Group during the late 1950s and mid-1960s in the course of his research and intended his experiences to “provide a few footnotes to the Bloomsbury record.” The result is an idiosyncratic first-person account that both dispels and magnifies the Bloomsbury phenomenon. While Stone finds philosopher G. E. Moore to be senile and describes Clive Bell as “just an old squire who laughs a lot and somehow got tied up in art,” Stone’s experience with these figures also inspires a vision of the Bloomsbury often represented in literary scholarship. Stone’s time spent with David and Angelica (Bell) Garnett “returns as a vision of latter-day Bloomsbury in full operation, a lovely setting with lively intelligent people, a glimpse of a world in which privilege and simplicity, art and books, good talk and good food came together in a most satisfying combination.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.