Collaborative Attention Work on Gender Agreement in Italian as a Foreign Language

ABSTRACT

In cognitivist Second Language Acquisition (SLA), attention and noticing are described as psycholinguistic processes that (may) have a role in language learning. The operationalization of such constructs, however, poses methodological challenges, since neither online nor off-line measures are coextensive with these cognitive processes that occur in the individual mind–brain. In contrast with such a perspective, the present conversation-analytic study re-specifies attention in social terms, as a nexus of publicly displayed actions that are jointly achieved by college level students of Italian as a foreign language as they engage in collaborative writing while planning for a group presentation to be performed in the second language (L2). More specifically, the article describes gender-focusing sequences that are initiated by attention-mobilizing turns with which a student directs her coparticipants’ attention to an oral or written item that is oriented to as possibly inaccurate in terms of gender assignment. The study shows the agentive role of students in identifying learnables and solving language-related issues and provides an example of how participants do learning as a socially situated and collaborative activity by enacting immanent pedagogies (Lindwall & Lymer, 2005).

THIS CONVERSATION-ANALYTIC STUDY addresses the cognitive constructs of incidental focus on form (Doughty & Williams, 1998), noticing (Schmidt, 2010), and attention (Robinson, 2003) and respecifies them in social terms by describing the learner-initiated, collaborative achievement of joint attention on linguistic forms during planning time. Specifically, the practice analyzed in this article concerns gender-focusing sequences with which college level students of Italian as a foreign language do collaborative attention work that focuses on accurate gender assignment with –e ending nouns. Such sequences are accomplished as the students engage in collaboratively writing the script for a classroom presentation to be performed in the second language (L2). The article thus gives an emic (i.e., participant-relevant) and praxeological (i.e., action-based) account of how participants do collaborative attention work on Italian linguistic forms as planning-related and observable language learning behavior (Kunitz, 2013; Markee & Kunitz, 2013). Through the sequences of collaborative attention work described here, the participants discover, co-construct, and act on emergent and student-selected objects of learning or learnables (Jakonen & Morton, 2015; Majlesi & Broth, 2012; Mori & Hasegawa, 2009). This article therefore contributes to the research on the ethnomethodology of learning as the study of “learning in and as the members’ phenomena” (Lee, 2010, p. 409; original emphasis).

In contrast with cognitivist second language acquisition (SLA), which treats attention and noticing as psycholinguistic, individual phenomena that occur at the perceptual level (Schmidt, 2010), the present study analyzes the situated nature of collaborative attention work as it becomes observable in the moment-by-moment unfolding of talk-in-interaction as participants orient to the accuracy of their script and ‘do grammar’ (i.e., engage with issues of linguistic accuracy through observable actions). Within the theoretical and methodological framework of Conversation Analysis (CA), attention work in general, and noticing in particular, are considered as socially distributed, interactional accomplishments that are implemented verbally and body-behaviorally (Schegloff, 2007) through observable actions. This study is thus in line with and extends CA/SLA research on focus on form, corrective feedback, interactional noticing, and word searches (Eskildsen, 2018a, 2018b, this issue); Fazel Lauzon & Pekarek Doehler, 2013; Greer, 2014, 2018; Jacknick & Thornbury, 2013; Kasper & Burch, 2016; Kääntä, 2014; Theodórsdóttir, 2018, this issue). Specifically, it responds to Kasper and Burch's (2016) call to examine students’ agency in selecting attention foci and potential learning objects, while re-specifying focus on form in praxeological, emic terms (see also Fazel Lauzon & Pekarek Doehler, 2013) through a detailed analysis of the embodied, material resources employed in the unfolding of student–student interactions.

ATTENTION AND NOTICING IN COGNITIVIST SLA

In cognitivist SLA, attention and noticing are psycholinguistic processes that occur inside the individual learner's mind and that are deemed to have a role in (conscious) language learning (for an overview of the Noticing Hypothesis, see Schmidt, 2010). In this view, which is embraced by researchers within the Interaction Hypothesis (Long, 1985), comprehensible input and an exclusive focus on meaning are not sufficient conditions for language learning. In fact, in order for input to become intake, learners need to bring their attention to (and therefore notice) linguistic features in the input through an incidental focus on form (Long & Robinson, 1998), as they are engaged in meaning-focused tasks. Swain (1995) also recognized an important role for output in that, by using language, learners may “notice what they do not know or know only partially” (p. 129).

A variety of studies, mostly of an experimental or semi-experimental nature, have been conducted in order to prove the role of noticing (and therefore attention) for learning. These studies have relied on a range of methodologies, both off-line (such as journal studies, questionnaires, retrospective reports, and stimulated recall; see Mackey, 2006; Robinson, 1996; Schmidt & Frota, 1986; Williams, 2005) and online (such as think-aloud protocols, note-taking and eye-tracking; see Godfroid, Housen, & Boers, 2010; Hanaoka, 2007; Rosa & Leow, 2004). However, as Robinson (2003) points out, the necessity of noticing for learning “is difficult to prove conclusively, given that no measurement instrument or technique can be assumed to be entirely coextensive with, and sensitive to, the contents of awareness and noticing” (p. 640).

From a CA point of view, the criticism against these methodologies and their goal (i.e., proving the necessity of attention/noticing) is rooted in three essential objections. First, most of the measures used in cognitivist SLA studies (ranging from retrospective reports to think-aloud protocols) depend on secondary, ethnographic self-report data and therefore rely solely on what the participants report or recall they do. CA, instead, works with primary data that give analysts direct access to what participants observably do. Second, experimental studies such as those involving eye tracking measures are highly controlled laboratory studies that ultimately lack ecological validity (see also Kunitz, 2013). Third, CA is agnostic as to the effectiveness of individual psycholinguistic constructs for learning to the extent that individual perceptual/cognitive phenomena only become relevant when observable in situ as participants' methods to do learning as a socially situated activity regardless of the outcome of such activity (e.g., Eskildsen & Theodórsdóttir, 2017; Firth & Wagner, 2007; Kasper & Wagner, 2011; Lilja, 2014; Pekarek Doehler, 2010; Sahlström, 2011; Theodórsdóttir, 2011). With its theoretical and methodological focus on the analysis of observable actions, CA thus considers attention and noticing in as much as they emerge as publicly displayed, social actions in and through talk-in-interaction.

The social dimension of noticing has been taken into account by cognitivist SLA researchers within Sociocultural Theory (SCT). These scholars (e.g., Storch, 2008; Swain, 2000; Swain & Lapkin, 2001) have analyzed Language Related Episodes (LREs), that is, stretches of talk where learners engage in collaborative, metalinguistic dialogue about their language use. LREs are thought to be important loci of learning because, from an SCT point of view (see for example Lantolf, 2011), learners’ intermental analyses of linguistic production facilitate individual — that is, intramental — language learning. In other words, the collaborative dialogue of LREs is examined in cognitive terms, as a window onto intramental cognitive processes. Within SCT, Storch (2008) has investigated the level of student engagement during LREs in the context of collaborative writing. Storch found that an elaborate level of engagement (characterized by conscious, verbalized reflections and by the production of metatalk) is more beneficial for language learning than limited engagement (operationalized as a simple noticing, i.e., the mentioning of a linguistic item). At the same time, studies on collaborative writing (Storch, 2005; Wigglesworth & Storch, 2009) demonstrated that students engaged in collaborative work produce more accurate texts than students who work individually.

The findings of these SLA/SCT studies are relevant for the present article, given its focus on collaborative attention work as a set of interactional practices through which participants orient to accuracy in and for writing (see the analysis). The theoretical and methodological framework, however, is radically different since SLA/SCT studies consider collaborative dialogue as a window into intramental phenomena, thereby viewing attention and noticing as essentially individual constructs. At the same time, these studies aim to show evidence supporting a specific theory of learning and thus maintain an etic (i.e., researcher-relevant) perspective that overlooks the sequential details of the unfolding interaction.

THE PRESENT STUDY

The present study, instead, framed within CA research on the achievement of joint attention, (a) is agnostic as to the nature of individual (or intramental) psycholinguistic processes, which lie outside of CA's methodological scope (Burch, 2014; Eskildsen & Cadierno, 2015; Hauser, 2013); (b) embraces a view of cognition as socially distributed, embodied, and extended (see for example Gallagher, 2005; Robbins & Aydede, 2009; for SLA, see, in particular Markee & Kunitz, 2013; Eskildsen & Markee, 2018); and (c) develops an emic (i.e., participant-relevant), sequential, multimodal analysis (Goodwin, 2013; Hazel, Mortensen, & Rasmussen, 2014; Majlesi, 2018, this issue; Mondada, 2014) of the verbal and other embodied actions through which attention is observably mobilized and a shared attention focus is reached. With such an approach, which is agnostic toward any exogenous theory of learning, it is possible to describe the displays of socially distributed cognition that participants make available to each other (and thus to analysts) in and through talk-in-interaction. Such description takes into account how participants laminate various semiotic resources to recipient-design their turns and thus indicate what they are attending to through the unfolding contextual configurations that emerge on a moment-by-moment basis.

Before moving forward, a word of caution concerning the terminological choices adopted here is in order. To avoid any confusion that might result from the use of the terms noticing and noticing turns,1 and to highlight CA's agnosticism as to whether and when a perceptual/cognitive noticing has occurred, in this article I will primarily focus on collaborative attention work that is done in and through embodied talk-in-interaction and that is prompted by attention-mobilizing turns.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Praxeological CA Perspective on Attention and Noticing

The line of CA research that is of most interest here is concerned with how interactants achieve a joint focus of attention as they orient to doing language learning. Specifically, two studies (Fazel Lauzon & Pekarek Doehler, 2013; Kasper & Burch, 2016) worked toward a praxeological respecification of focus on form (see Doughty & Williams, 1998), while other studies (Eskildsen, 2018a, 2018b, this issue; Greer, 2014, 2018; Jacknick & Thornbury, 2013; Kääntä, 2014; Theodórsdóttir, 2018, this issue) explored the resources through which participants accomplish interactional noticing. What all these studies share is the attempt to describe attention and noticing as joint processes that are interactionally organized in the contingent unfolding of multimodal talk-in-interaction as participants are engaged in or temporarily orient to language learning activities. It is in the local, sequential organization of turns that the participants’ attention focus becomes observable to both participants and analysts. It is in interaction that language learning behaviors (Markee, 2008; Markee & Kasper, 2004) and learning affordances become manifest.

The scholars pursuing this line of CA research analyzed interactions occurring in different settings: the classroom (Fazel Lauzon & Pekarek Doehler, 2013; Jacknick & Thornbury, 2013; Kääntä, 2014) and beyond, that is, ‘the wild’ (Eskildsen, 2018a, 2018b, this issue; Greer, 2014; Hellermann et al., 2018; Kasper & Burch, 2016; Theodórsdóttir, 2018, this issue; Wagner, 2015). Particularly relevant for the present article is Kasper and Burch's (2016) call to focus on “the students’ agentive participation” (p. 199), and on the interactional competencies that students/L2 speakers enact to achieve joint attention on a specific form (see also Theodórsdóttir, 2011). Another important insight concerns the potential relevance of the broader activity (the overall interactional event) in which the participants are engaged (e.g., dinner in Greer, 2014; answer-correction in the classroom in Kääntä 2014; communicative practice in the classroom in Fasel Lauzon & Pekarek Doehler, 2013) and its impact on local, situated actions that unfold within such activity. For example, the goal of the broader activity (which, in this study, consists of planning for an oral presentation in the L2) might have an impact on the initiation of collaborative attention work and on its sequential trajectory. Indeed, by exploring group-based planning sessions, the present study explores what students agentively orient to and shows that their interpretation of the broader activity as collaborative writing does have an impact on what they attend to.

Research on Grammar Searches in the L2

Finally, two CA studies on grammar searches in the L2 are particularly relevant for the present article: Kurhila (2006) and Markee & Kunitz (2013). Both studies analyze grammar searches as interactional achievements that mobilize the participants’ attention to a specific grammar form. In these datasets, the initiation of the attention-mobilizing sequence is done by an L2 speaker through talk (especially with cutoffs, repetitions, and self-corrections) and other embodied resources (e.g., eye gaze). Through these resources, and particularly through modified repetitions of the targeted word/phrase, the speaker's course of action becomes recognizable as a grammar search. In addition, while the modified repetitions of the problematic word/phrase indicate difficulty, they also provide possible alternatives and therefore display the speaker's agency in trying to solve the grammar problem.

Indeed, in Kurhila's (2006) corpus of conversations between first language (L1) and L2 speakers, the L2 speaker's display of uncertainty alone does not represent an immediate request for help. Instead, the L2 speaker starts the search as self-directed and then other-directs it via shifts in eye gaze, for example. That is, the L2 speaker orients to her identity as that of an agentive learner who is trying to solve the problem on her own before asking for help. Nevertheless, when the L1 speaker completes the search by providing an outcome, such outcome is offered and accepted as “undebatable” (p. 126). Overall, then, grammar searches are loci where language identities clearly emerge: The L2 speaker displays her less knowledgeable position by showing uncertainty, while the L1 speaker assertively completes the search.

But grammar searches may also occur among L2 learners and in settings, as is the case in the present study and in Markee & Kunitz (2013), that are characterized by an epistemic ecology in which none of the participants is oriented to as the language expert. Instead, linguistic identities (i.e., identities related to language expertise) are ever shifting and collaboratively negotiated on a moment-by-moment basis through the display of epistemic stances that reveal different levels of (un)certainty. As mentioned before, Markee and Kunitz (2013) explored the same corpus analyzed in the present article (i.e., group-based planning sessions) and aimed to show how planning work is done “as real time behavior” (p. 656). Their analysis illustrates how grammar searches are enacted as socially distributed planning practices aimed to achieve grammatical accuracy. Overall, the study by Markee and Kunitz (2013) shows that CA is particularly apt at describing how participants do grammar and how they display and monitor their epistemic stances as they do language work.

PARTICIPANTS AND SETTING

This study draws on a dataset of six planning sessions conducted by two groups of students of Italian as a foreign language at a US research university (groups A and B). The total number of participants was five. The students were enrolled in a third-semester, content-based course. Both groups engaged in three planning sessions and a final, ungraded in-class presentation;2 each session lasted 30–50 minutes.

The group-based planning sessions explored in this study are ideal loci to observe the students’ agency in discovering their own learnables (Jakonen & Morton, 2015; Majlesi & Broth, 2012; Mori & Hasegawa, 2009). In these sessions, in fact, the participants interacted outside the classroom to perform classroom-related tasks. Specifically, they engaged in the goal-oriented activity of planning a classroom presentation to be performed in Italian. As it turns out, the students interpreted the planning activity as largely consisting of collaboratively writing a script for their presentation. In doing so, they were mainly concerned with the content of their presentation and with the creation of possible script lines that would best express such content. In other words, they seemed mostly concerned with meaning. However, in some cases, as they were writing down a specific part of the script line that had been proposed orally, they engaged in focus on form both on vocabulary and grammar. Since the students appeared to be specifically concerned with gender assignment issues, the present paper focuses on such instances of collaborative attention work. Overall, the students’ engagement with language forms reveals their orientation to the accuracy of their script. Moreover, as the analysis will show, the broader activity of planning established the relevance of a display of agreement among the co-participants (Kunitz, 2013) before ratifying in writing the chosen form. In the present dataset, then, collaborative attention work is tied to the participants’ unfolding interpretation of the broader planning activity and of the outcome it should produce; that is, an accurate script. As such, the attention-mobilizing turns are clearly done “for cause” (Keisanen, 2012, p. 201) and their occurrence in the unfolding interactional sequence is conditioned by the current state of the script as an emergent artifact (Kunitz, 2013). It is in this sense, then, that such turns are done for writing:3 They emerge as one of the participants is writing, they directly concern the activity of writing, and they have material consequences on the final written outcome.

DATA COLLECTION AND METHODOLOGY

The planning sessions and the classroom presentations were videotaped with a digital camera. The gender-focusing sequences that were identified were transcribed following standard CA conventions (Jefferson, 2004, see Appendix). Later, frame grabs were added in order to capture the participants’ embodied actions and eye gaze behaviors; verbal descriptions are instead used for rapid gestures (such as nodding) that are hard to capture with a still image. A plus sign indicates the co-occurrence of embodied actions (represented with frame grabs or verbal descriptions) with talk or silence. Only one translation line is provided (with information concerning the gender of modifiers and nouns: F for feminine, M for masculine), unless word order calls for a more idiomatic version of the translation. At the methodological level, the analysis relies on primary data; that is, video recordings and the exogenous cultural artifacts that the participants observably talked or “embodied” into relevance. This type of data allows for the direct observation of the participants’ behavior in the material ecology of its embodied emergence.

GENDER-FOCUSING SEQUENCES IN THE DATASET

Gender-Focusing Sequences

The participants in this study talked into relevance gender assignment issues with –e ending nouns (see the next section) in what I call “gender-focusing sequences.” In these sequences, the participants did grammar4 as they observably mobilized their attention to gender assignment and collaboratively negotiated alternative forms. Overall, seven gender-focusing sequences were identified as initiated by the speaker who orally produced the part of the script line containing the targeted noun phrase. Typically, the speaker initiating the sequence is also in charge of writing (6/7 instances). Table 1 sketches the actions that characterize the gender-focusing sequences in the present dataset. However, as the analysis will show, the level of interactional work that is accomplished by the participants as they agree on a specific rendition of the noun phrase is far from linear.

| Sequential Trajectory |

|---|

| (a) Mobilizing attention to a (problematic) form |

| (b) Providing a candidate form |

| (c) Accepting the candidate form |

| (d) Writing the accepted form |

Each sequence is initiated by an attention-mobilizing turn that directs the co-participant's attention to a noun phrase that was produced orally and that was either about to be written or already written (in full or partially). The attention-mobilizing turn characterizes the targeted noun phrase as possibly inaccurate,and the problem is cast in terms of determiner–noun agreement. Specifically, the determiner in the noun phrase (either the definite article il, masculine singular, or la, feminine singular) is inserted in a question-formatted turn (is it + determiner; 3/7 instances), or an alternative modifier is offered (determiner + noun; 3/7 instances). In only one case is attention work initiated through the use of metalanguage (see Excerpt 2).

All attention-mobilizing turns are delivered with rising, try-marked intonation (Sacks & Schegloff, 1979), which indicates uncertainty and might invoke a confirmation from the co-participants. Their collaboration may also be solicited through eye gaze (see Excerpts 1b and 2). Indeed, various gaze behaviors accompany the delivery of attention-mobilizing turns. In some cases (Excerpts 1a and 1b), the speaker (initially) averts her gaze from the co-participants, thereby possibly indicating that a solitary grammar search is underway (see Goodwin & Goodwin, 1986 for a description of this practice). In other cases, she looks at the computer screen in front of her or at the co-participant's script, thus treating these artifacts as possible resources to address the trouble. However, in only one case the participants consult an online dictionary. Eventually, a candidate form is produced, agreed upon, and ratified in writing (for the role of inscription, see also Eskildsen & Theodórsdóttir, 2017; Kunitz, 2013; Streeck & Kallmeyer, 2001).

The Grammar Issue: Gender Agreement With –e Ending Nouns

In the gender-focusing sequences identified in the data the participants attend exclusively to gender assignment with –e ending nouns, which constitute only 20.6% of the total number of nouns in the Italian basic vocabulary (Chini & Ferraris, 2003). Now, if gender assignment in general can be a challenge for L2 learners of Italian, especially if their L1 lacks a noun classification system based on gender (Chini, 1995), –e ending nouns are all the more problematic. In fact, -e ending nouns are less frequent and, by being less clearly related to the feminine or the masculine gender than –o ending nouns (generally, but not always masculine) and –a ending nouns (generally, but not always feminine), they have less regular gender assignment. Thus, the fact that the participants in this study mobilized their attention only to –e ending nouns suggests that they are aware of the specific difficulties posed by this type of nouns (see Excerpt 1b). This lends support to prior studies on the acquisition of gender in L2 Italian (Chini, 1995; Chini & Ferraris, 2003; Gudmundson, 2012), which have shown that gender assignment and agreement with –e ending nouns are problematic for learners.

Analysis

The analysis focuses on three excerpts that represent three out of the seven gender-focusing sequences identified in the dataset: Excerpts 1a and 1b (Group A), targeting the noun dolce (‘dessert’), and Excerpt 2 (Group B), targeting the noun tradizione (‘tradition’). In all three cases the participant initiating the gender-focusing sequence is engaged in writing; however, there are some differences as to whether the material action of writing has already started (Excerpts 1b and 2) or not (Excerpt 1a) when the sequence is initiated. To enhance the readability of the transcripts, each excerpt has been divided into various parts.

Sequences Focusing on Dolce (‘Dessert’)

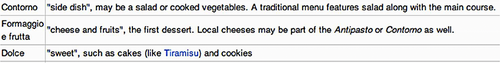

During the second planning session, the participants in Group A (John, Mary, and Lucy)5 plan the final part of their presentation: They will list all the courses in a typical Italian meal by illustrating a restaurant menu. They therefore search the English pages of Wikipedia for Italian meal structure and then work on formulating a brief definition of each course in Italian. The final product of this activity is a written script that the participants are to perform during the presentation. Excerpts 1a and 1b illustrate the participants’ work on the item cheese and fruits on the Wikipedia page (Fig. 1).

In lines not reported here, Mary formulates and writes a script line to introduce the new item on the menu, cheese and fruits (see Fig. 1). The line so far reads: dopo il contorno, il formaggio e frutta (‘after the side dish, the cheese and fruits’). Excerpt 1a/Part 1 picks up the talk as Mary stops writing, lifts her head up, and looks at the computer screen where the Wikipedia page appears (2; Mary is sitting in the middle, John to her right, and Lucy to her left). As the analysis will show, Mary orients to the formulation of a description of the cheese and fruit course.

EXCERPT 1a. Dolce – Part 1

|

The hesitation token u:hm: (3) and the 2.0 second pause (4) indicate that Mary is temporarily stalled in formulating the continuation of the script line so far, while her rather intent gazing at the screen (5) suggests that she is looking at the information on the Wikipedia page as a potential source for her line. Finally, Mary delivers a candidate continuation of the script line by saying anche è la prima dolce? (‘also it is the first dessert’, 6–7), with inaccurate agreement (la and prima are feminine, dolce is masculine). As she says dolce (7), Mary keeps gazing at the screen and points to it (8), thereby showing that she is basing her script line on the information provided by Wikipedia. Specifically, she is orally providing a candidate translation for the Wikipedia description of cheese and fruits as the first dessert (Fig. 1). At the same time, the rising, try-marked intonation in Mary's turn establishes the relevance of a response from Mary's co-participants who, however, remain silent (9) as they look at the screen (8). It is after this silence that Mary engages in a solitary grammar search and initiates the gender-focusing sequence. Specifically, she produces the perturbation u:hr (10). Right afterwards, she looks up, enacts a thinking face (11; see Goodwin & Goodwin, 1986), and characterizes the prior use of the feminine form of the definite article, la (6), as problematic by producing the masculine form of the article, il-, followed, after a short pause, by il dolce? (‘the dessert’, 10), with try-marked upward intonation. Mary's turn accomplishes two actions: (a) It displays her epistemic stance of uncertainty, and (b) it makes the problem recognizable as an issue of article–noun agreement. After a 0.3 second pause (12), Lucy nods (14), but her embodied action is not visible to Mary who has shifted her gaze to the screen (not reproduced in the transcript). Finally (Excerpt 1a/Part 2), Mary self-completes the search with anche è il primo: (0.2) dolce¿ (‘also it is the first dessert’, 15), which represents an accurate reformulation of Mary's turn in 6–7 (anche è la prima dolce). That is, she replaces the feminine forms of the article (la) and the modifier (prima) with the corresponding masculine forms (il and primo).

EXCERPT 1a. Dolce – Part 2

|

The matter, however, is not settled, as indicated by the slightly rising, try-marked intonation of Mary's turn (15). A silence ensues (16), then Lucy nods (18). However, her embodied action is not seen by Mary, who pursues a response from her co-participants by moving her hand to the screen (18) and eventually pointing toward a specific part of it (34) as she says: °°like°° the first dessert (19). Through her pointing gesture, which secures both John and Lucy's eye gaze (21), Mary explicitly shows that her formulations in Italian (la prima dolce/il primo dolce) are based on the formulation appearing on the Wikipedia page displayed on the screen. While earlier Mary seemed to be engaged in a solitary search, now she explicitly invites John and Lucy to provide a response to her search, in order to determine whether anche è il primo dolce could overall be a good rendition of the first dessert. While John's action in 20 is not clear, after another short pause (22), during which Mary turns her head and looks at him (23), John accepts Mary's formulation with O:h okay (24) and, after a 0.3 second pause (25), he further confirms his acceptance with yeah (27). The gender-focusing sequence then comes to an end, with Mary starting to write (29): John's observable acceptance is enough to ratify the accuracy of her formulation, which can now be written (Lucy nods in 26, but again her action is not seen by Mary).

However, what could Mary be writing down at this point? In fact, it is hard to determine what John is actually accepting, since he does not explicitly engage with the gender assignment issue brought up by Mary. He might as well be simply acknowledging that a translation of the first dessert is an acceptable continuation of the script line so far. The consequences of the ambiguity of John's acceptance emerge in Excerpt 1b, which illustrates another gender-focusing sequence targeting dolce and initiated by Mary right after Excerpt 1a.

EXCERPT 1b. Dolce – Part 1

|

The excerpt picks up the talk as Mary stops writing, lifts her head up (31), and points her right index finger at the computer screen (33) as she produces the question-formatted turn: is it (0.2) il dolce? (30 and 32), with emphasis on the definite article il. This new attention-mobilizing turn again frames the problem in terms of article–noun agreement as Mary questions whether il is indeed the accurate article for dolce. However, while in 10 (il- (0.3) il dolce?, Excerpt 1a/Part 1) the relevance of a response from the co-participants was established only by the upward intonation at the end of Mary's turn, the grammatical packaging of the turn in 30 and 31 as a yes/no question strongly establishes the conditional relevance of a response. In other words, with her turn Mary not only mobilizes her co-participants’ attention, but also explicitly invites their collaboration in settling the matter, while her pointing gesture appears to establish once again the connection between the formulation she proposes and the Wikipedia page. In response to Mary's actions, both John and Lucy shift their eye gaze to Mary (33). Since no verbal response ensues (34), Mary proposes, with lower volume, a candidate alternative with la dolce? (35), thereby transforming her original yes/no question into an alternative question. As Mary delivers this alternative formulation, John shifts his eye gaze from Mary (33) to the computer screen, while Lucy looks up and Mary looks down (36). These gaze behaviors, which are maintained throughout the following 0.4 second pause (37), suggest that the participants are not ready to commit to either il dolce or la dolce yet.

Finally, as Excerpt 1b/Part 2 shows, John provides the responding action to Mary's attention-mobilizing turn by saying ci sono:: (.) #u:::h# (1.0) la prima dolce¿ (‘there are the first dessert’; 38–39).

EXCERPT 1b. Dolce – Part 2

|

With this turn, John does more than choosing one of the options proposed by Mary (il dolce in 30 and 32 vs. la dolce in 35). In fact, he frames the targeted noun phrase within a new formulation of the script line (ci sono, ‘there are’, versus anche è, ‘also it is’, used by Mary in 15), and produces feminine gender agreement on both the article (la) and the adjective (prima). Furthermore, John's response to Mary is achieved as a grammar search, as indicated by the token u:::h (39) and by the embodied action of lifting his eyebrows (40). At the same time, John's alternative formulation of the script line is not characterized by a strong epistemic stance, as indicated by the slightly upward intonation of John's turn, which invites confirmation from his co-participants.

After one beat of silence (41), John self-selects and produces the feminine form of the article (la) with rising intonation (42), and then immediately produces the rush-through I wanna say la. With this action, he displays his understanding of the problem in the same terms proposed by Mary's attention-mobilizing turns; that is, as an article–noun agreement problem. At the same time, John conveys an epistemic stance of mild certainty: as indicated by the upward intonation on the first la and by the use of the modal wanna, the accuracy of la is not a matter of fact; rather, it is the option that John is willing to support. By saying that she wants to say la too (43), Mary expresses agreement with John and affiliation with his stance, and soon afterwards she starts writing (46). Concurrently, in partial overlap with Mary's turn, John repeats >I wanna say< la: (44–45), while Lucy nods as John says la:. In conclusion, John's and Mary's turns in 42–45 are offered as accounts that justify the outcome of the sequence as a solution that is accurate enough to be ratified in writing. In 48 (Excerpt 1b/Part 3), however, John produces a claim of insufficient knowledge (°but I don't know.°; see Sert & Walsh, 2013) that downgrades his epistemic authority. His co-participants, however, show no uptake of this action.

EXCERPT 1b. Dolce – Part 3

|

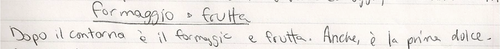

Specifically, Mary, who is now fully engaged with the action of writing, repeats the revised script line (anche è la prima dolce, 49), with low volume. She is thereby displaying that the gender-focusing sequence has come to an end and that agreement has been reached on dolce as a feminine noun. The outcome indeed receives its final ratification as it is incorporated in Mary's written script (Fig. 2).

As Mary is engaged in writing, however, John announces: not su:>re about< those e:s ma:n (51). With this turn, John attributes the origin of his uncertainty in determining the gender of dolce to the more general problem represented by all –e ending nouns. Thus, his statement represents an insightful metalinguistic appreciation of the difficulties related to gender assignment with –e ending nouns. Mary then expresses agreement and affiliation with John by saying I know (53). As the ratified solution testifies (la prima dolce), the participants reach insights that are simultaneously correct and incorrect: they display their knowledge of the required gender agreement of modifiers with nouns, even though they incorrectly assign the noun dolce to the feminine gender. Moreover, they conclude the sequence with a metalinguistic comment (not su:>re about< those e:s ma:n, 64) that displays their awareness, that is, their previous noticing, of the difficulty of assigning gender to –e ending nouns; in other words, the participants verbalize their uncertainty concerning accurate gender assignment with –e ending nouns and orient to it as a learnable. Ultimately, the gender focusing sequences reproduced in Excerpts 1a and 1b seem to provide an observable example of the hypothesis advanced by Truscott (1998), according to whom noticing might enhance the acquisition of metalinguistic knowledge, but might not (or perhaps not necessarily) foster the acquisition of language. The data presented here, in fact, show that these students, while being observably aware of potential gender assignment problems with –e ending nouns and while being able to formulate metalinguistic comments concerning this issue (see John in 51 and Mary's agreement in 53), still assign inaccurate gender to the targeted noun.

Sequence Focusing on Tradizione (‘Tradition’)

During the second planning session, the participants in group B, Jenny and Emily, brainstorm what they know about Carnival in Venice and look for more information online. Excerpt 2 occurs later in the session, when Jenny and Emily are formulating the script lines that Jenny will animate (Goffman, 1981) during their presentation on Carnival traditions. Specifically, Jenny would like to say that Carnival puppet shows are an old tradition (1), a tradition that has been popular for many centuries (9–10).

Excerpt 2/Part 1 picks up the talk as Jenny proposes, for the description of puppet shows, the script line: quest(a) è un tradizione molto vecchio:, (1; ‘this is a very old tradition’). In this first oral emergence of Jenny's script line, gender assignment is inaccurate, since tradizione is a feminine singular noun, while the indefinite article un and the adjective vecchio (‘old’) are masculine. Gender agreement on the demonstrative quest(a) (‘this’), however, seems to be accurately produced. In any case, at this point in the planning process, the participants do not orient to doing grammar work and the gender issue goes interactionally unnoticed. Indeed, with or (3), Jenny orients to the formulation of an alternative version of the script line; by turning first to Emily (5), sitting to her right, and then to the computer screen (7), she seems to indicate her co-participant and the internet as possible sources of alternative formulations. Eventually, Jenny tries to formulate an alternative script line (8–9), but its delivery is characterized by pauses, elongations, and hesitation tokens; the script line is left incomplete (‘puppet shows is’; 9) and Jenny finally resorts to English to deliver what she would like to say: Puppet shows have been popular for many centuries (10–12). The slightly upward intonation and the direction of her gaze (13) indicate that Jenny is invoking Emily's help. Emily responds by engaging in a word search targeting the word popular (16–17) and then starts to look online (19; see Excerpt 2/Part 2), presumably for a translation.

EXCERPT 2. Tradizione – Part 1

|

EXCERPT 2. Tradizione – Part 2

|

|

After 5.6 seconds, during which Jenny alternatively looks at the screen (19 and 23) and at her notebook (21), Jenny finally puts her pen on her notebook (25) and starts writing (27). A close look at the video allows us to say that, by 30, Jenny has possibly written questa è (‘this is’). In 31 she delivers a very soft è: (‘is’), then seems to be writing una (‘a’, 33). Jenny's written script line so far then is: questa è una (‘this is a’), with accurate feminine agreement. At this point, Jenny lifts her pen, keeps looking down at her notebook (35) and starts producing the attention-mobilizing turn è:: tradizione (0.6) ma:sculine °or° (0.2) maschile o femminile:¿ (‘is tradition masculine or feminine’; 34, 36, 38, and 40). This is the only instance in the dataset where the gender issue is formulated in metalinguistic terms.

As she delivers the word masculine (36), Jenny turns toward Emily (37). With the question format and her change in bodily posture Jenny thus conveys her orientation to Emily as a potentially knowledgeable participant. Indeed, Jenny manages to mobilize Emily's attention, since Emily finally abandons her online search and turns toward Jenny (41). Her response, however, is not immediately forthcoming (42).

Jenny then delivers tradizione? (44) with upward intonation (Excerpt 2/Part 3), as she keeps looking at Emily (43): With this action she pursues a response from her co-participant, while reminding her of the source of the problem.

EXCERPT 2. Tradizione – Part 3

|

After a short search (see the pauses in 42 and 46, the hesitation token u:::h in 45), during which Emily keeps her gaze down to Jenny's script, Emily finally provides the outcome of the gender-focusing sequence: tradizione is a feminine noun (47). As Emily is delivering the last syllable of femminile (‘feminine’), Jenny turns to her notebook (48), thereby showing that, upon receipt of this piece of information, she can orient again to the action of writing the script. After orally expressing agreement with Emily (okay, 49) and upon hearing a further confirmation from her (yeah, 51), Jenny starts writing (54) as Emily repeats the line so far: questa è (0.4) una:, (0.2) tradizionale: (‘this is a traditional’, with tradizionale instead of tradizione; 53 and 56). In partial overlap with Emily's turn, Jenny whispers the end of the word that she is possibly writing: °°zio::ne°° for tradizione (57). The written version of the script line appears in Figure 3: questa è una tradizione molto vecchio (‘this is a very old tradition’); the adjective vecchio (‘old,’ masculine) does not agree with tradizione. However, this gender agreement issue is not talked into relevance by the participants.

Summary of Analysis

The analysis of these excerpts has shown that, as the participants are engaged in collaborative writing, they orient to the accuracy of gender assignment with –e ending nouns. This issue is talked into relevance through attention-mobilizing sequences that target noun phrases which are produced orally and are about to be written (Excerpt 1a) or which are already in the process of being written down (Excerpts 1b6 and 2). In these three excerpts the sequence is initiated by the participant who is materially writing the relevant part of the script. The sequence-initiating turn marks the targeted noun phrase as possibly inaccurate and, at different levels of explicitness, invites the co-participant(s) to provide a candidate form, thereby showing an understanding of the ongoing activity as a collaborative effort and an orientation to the co-participant(s) as possibly knowledgeable in lexicogrammatical matters. In all three cases a pause ensues. In response to it, the speaker who initiated the sequence either produces a form herself (Excerpt 1a) or pursues a response from the co-participants (Excerpts 1b and 2). Such form is then subject to the co-participants’ agreement, which is made relevant by the broader activity of collaborative planning. Once agreement is reached (with agreement tokens like okay in Excerpts 1a and 2, and with I do too in Excerpt 1b), the participant–writer orients to ratifying the outcome of the gender-focusing sequence in writing. The outcome may (Excerpt 1a, Excerpt 2) or may not (Excerpt 1b) be accurate.

CONCLUSION

In contrast with cognitivist SLA and its treatment of attention and noticing during focus on form as individual, psycholinguistic processes that may (or may not) foster language learning, the present article has shown that attention to form can be re-specified in social terms by describing how students recruit each other's participation in order to attend to language forms and collaboratively perform grammar work on them. Specifically, with its emic perspective and the praxeological, multimodal, and sequential analysis that takes into account the situated nature of collaborative attention work, this study contributes to CA research on the collaborative, interactional, local achievement of a joint focus of attention on form (Fazel Lauzon & Pekarek Doehler, 2013; Greer, 2014; Jacknick & Thornbury, 2013; Kasper & Burch, 2016; Theodórsdóttir, 2018) and it emphasizes the agentive role of L2 speakers in mobilizing the co-participants’ attention on the learnables they select (Jakonen & Morton, 2015; Lee, 2010; Majlesi & Broth, 2012; Mori & Hasegawa, 2009) in the moment-by-moment unfolding of planning talk (Eskildsen & Markee, 2018; Fazel Lauzon & Pekarek Doehler, 2013; Kasper 2009; Kunitz, 2013, 2015; Markee & Kunitz, 2013; Pekarek Doehler, 2010; Schegloff, 1991). The gender-focusing sequences analyzed here could also be considered as epistemic search sequences (Jakonen & Morton, 2015), in which the participants initially orient to gender assignment as an uncertain matter (and, as such, as a learnable); alternative options, marked by various epistemic stances, are produced until the participants finally come to an agreement. In such sequences the participants’ attention to and awareness of linguistic forms are done as publicly displayed behaviors and socially distributed cognition becomes observable as participants do learning (Firth & Wagner, 2007; Pekarek Doehler, 2010; Sahlström, 2011).

In the small dataset analyzed here, what seems to be triggering the participants’ attention to form in the first place is their engagement in collaborative writing, together with their emic orientation to producing an accurate script for their presentations. In other words, these gender-focusing sequences are accomplished for writing and for writing accurately. What does this have to say to language teachers and, more specifically, to the participants’ teachers? Clearly, these third-semester students emically orient to linguistic accuracy as an important criterion that guides their planning process (see also Kunitz, 2013). Even though the oral presentation prepared by the students during planning time was ungraded, it is worth specifying that linguistic accuracy was not a grading criterion used to assess regular presentations. In other words, the students were not invited to focus on language forms when they were preparing for similar in-class presentations. So, what happened in these gender-focusing sequences is truly incidental and learner-initiated focus on form (see Doughty & Williams, 1998 for the distinction between learner-initiated and induced focus on form). This finding suggests that group work and the students’ own interpretation of the final outcome for the planning activity as a written script might have led them to attend to language forms, to identify learnables, and to do grammar, while orienting to each other as possible sources of knowledge. Ultimately, students and teachers seem to conceptualize the final task in different ways: For teachers, presentations are essentially an oral endeavor7 and, as such, linguistic accuracy is not crucial, unless it hinders comprehensibility; for the participants, presentations have an important written component represented by the script (Kunitz, 2013). This finding, then, clearly speaks to the difference between task-as-workplan and task-as-activity (see Coughlan & Duff, 1994; for a discussion from a CA perspective, see Hellermann & Pekarek Doehler, 2010) and suggests that teachers should closely monitor the planning process in the classroom to make sure that students orient to the criteria that are set by the teachers for each specific task.

At the same time, what students orient to and achieve on their own should not be discarded a priori. For example, given the findings of the present study, teachers might keep in mind that the design of collaborative tasks whose outcome is a written text (as is the case here with the presentation script) could lead students to do learning through joint orientation to language forms. Furthermore, it might be interesting for teachers to see to which learnables students emically orient, which level of knowledge they might display, and how they solve linguistic issues. In the case described here, the students show their awareness of the requirement for gender assignment and agreement in Italian. Then, to achieve accurate gender assignment with –e ending nouns, they essentially sound out whether a specific form of the definite article is accurate for a specific noun; this practice seems a way of remembering the accurate form.

In conclusion, this study provides data that can be used for teacher training purposes to illustrate a) the potential discrepancies between the teacher's conceptualization of the goal of an activity and the students’ interpretation of it, b) the emic practices enacted by students as they do learning, c) the criteria they orient to (i.e., accuracy), and d) the learnables they identify. Studies of this kind (see also Kunitz & Skogmyr Marian, 2017) are therefore useful to show how students achieve tasks as instances of “local educational order” (Hester & Francis, 2000). The findings of such studies can then inspire the design of tasks that take into account the students’ immanent pedagogies (Lindwall & Lymer, 2005).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I wish to thank Numa Markee for his collaboration on an earlier version of this paper. Many thanks also to the editors of the special issue and to the anonymous reviewers.

NOTES

APPENDIX

Transcription Conventions

| . | Falling intonation |

| , | Low-rising intonation |

| ¿ | Slightly rising intonation |

| ? | Rising intonation |

| - | Cut-off |

| : | Elongation of the preceding sound |

| word | Emphasis/stress |

| ↑ | Rising shift in intonation |

| ↓ | Falling shift in intonation |

| CAP | Loud volume |

| lower case | Normal conversational volume |

| °word(s)° | Lower volume than surrounding talk |

| °°word(s)°° | Whisper |

| >word(s)< | Speeded up delivery |

| <word(s)> | Slowed down delivery |

| (.) | Micropause (one beat) |

| (1.0) | Pause of one second |

| (0.2) | Pause of two tenths of a second |

| = | No gap (within a turn, between turns) |

| [] | Overlapping talk |

| .hhh | In-drawn breath |

| hhh | Hearable aspiration or laughter token |

| ( ) | Unintelligible talk |

| ((comment)) | Verbal description of actions or voice quality |

| + | Indicates the start of embodied actions in relation to talk |

| Italics | English translation |