The impact of interface on ESL reading comprehension and strategy use: A comparison of e-books and paper texts

Abstract

The use of e-books in postsecondary education is projected to increase, yet many English as a second language (ESL) institutions have not yet incorporated e-books into their curricula, in part due to a dearth of research regarding their potential impacts on ESL reading comprehension and strategy use. This study fills a gap in the existing research by investigating the impacts of contemporary e-books on ESL strategy use and reading comprehension, in comparison to paper texts. Twenty-two high-intermediate ESL participants were separated evenly into a paper text group and an e-book group. They were given pretests, support strategy mini-lessons, reading sessions with observation, posttests, surveys, and delayed posttests. Independent-sample t-tests revealed no significant difference between the groups’ reading comprehension rates; however, reading strategy use and frequency varied between groups. Though the majority of e-book participants had not previously used e-books for learning, they reported preferring them over paper texts after the reading sessions were completed. The study's findings offer some support for the incorporation of e-books in ESL curricula. In addition, the findings suggest that instructors provide e-book strategy lessons to students so they can appropriate the technology effectively.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 1968, postgraduate student Alan Kay fostered the idea of the Dynabook, “a portable interactive personal computer, as accessible as a book,” which utilized wireless internet and a touch-screen (MacWilliam, 2013, p. 2). This idea later became the Apple Newton MessagePad, the first PDA (personal digital assistant) with an e-reader. Later, many companies developed e-readers with increasing functionality, which have evolved into the e-readers of today. And as technology improves, the reading experience does as well.

E-books have entered postsecondary English as a second language (ESL) programs, and they are becoming common among students, who typically require many books for their academic classes. Even if students report that they do not prefer e-books, they use them because they find them to be necessary or much more practical (Chou, 2012). However, researchers have not yet reached a consensus on whether e-books are beneficial, neutral, or detrimental to the second language (L2) reading experience. Some proposed benefits are that e-books increase oral reading fluency (Papadima-Sophocleous, Georgiadou, & Mallouris, 2012), and readers find them to be quick to learn and easy to read and navigate (Wilson, 2003). Kol and Schcolnik (2000) found that, after training ESL students how to read on screen, there was no difference in reading comprehension between e-texts or paper texts, which suggests no additional value but no harm in using e-books. However, others have found that reading with e-books lowers comprehension (Lam, Lam, Lam, & McNaught, 2009), limits strategy use (Chou, 2012), and causes eye fatigue and lower reading performance (Kang, Wang, & Lin, 2009). This ongoing conversation is the impetus for the current study, which investigates the impacts of e-books on ESL reading comprehension and strategy use.

Next, a literature review will discuss the impacts of e-books on ESL reading comprehension and strategy use, especially support strategies, which are the main focus of this study. Additionally, this study's theoretical framework will be discussed. Then the current study will be explained: its research questions, methodology, results, discussion, and implications.

1.1 E-texts in Second Language Education

Scholars have made optimistic projections about the potential of e-books. For example, Kol & Schcolnik (2000) and Chou (2012) believe that paper-based books will become a secondary source in academia and that e-books will become mainstream. This may be because of the e-books’ continually improving accessibility, portability, storage, cross-referencing, screen resolution, readability, and text manipulation features, such as underlining.

Student preference for electronic texts is increasing as well (Mercieca, 2003). Digital libraries are becoming exceedingly common, and book publishers are allowing users to buy and loan digital books from personal computers (Kol & Schcolnik, 2000). Even if students report that they do not prefer e-books, they use them because the find them necessary or much more practical (Chou, 2012). Despite these predictions, there are very few studies regarding how electronic reading impacts L2 students in academia (Anderson, 2003).

1.2 ESL Reading and Strategies

Academic reading ability is considered to be one of the most essential skills for university students (Chou, 2012). ESL reading comprehension is affected by many factors, such as proficiency level, specific reading skills (or strategies), and reading purpose (Evans, Hartshorn, & Anderson, 2010). This is true whether one is reading e-books or paper texts, although reading strategies, or skills as Evans et al. describe them, are implemented differently with the two media.

Reading strategies are the tactics learners use, such as underlining unfamiliar words, to achieve their reading goals. Not surprisingly, when ESL students use reading strategies, they make gains in reading comprehension (H. C. Huang, Chern, & Lin, 2009), and skilled ESL readers use a variety of reading strategies frequently (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 1994). Accordingly, many L2 reading experts (e.g., Anderson, 2003; Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002, Oxford, 1990; Sheorey & Mokhtari, 2001) have created taxonomies of effective L2 reading strategies.

One such prominent taxonomy comes from Mokhtari and Sheorey's (2002) Survey of Reading Strategies (SORS). The SORS instrument divided reading strategies into three main categories: global strategies, problem-solving strategies, and support strategies. Because this classification was adopted for the current study, a discussion of each category is warranted.

Global strategies are “intentional, carefully planned techniques by which learners monitor or manage their reading,” such as trying to predict what will happen next in the reading (Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002, p. 4). Problem-solving strategies are “localized, focused techniques for use when problems develop in understanding” (p. 4)—for example, rereading a passage to ensure comprehension. Support strategies are “basic support mechanisms intended to aid the reader in comprehending the text,” such as taking notes (p. 4). Unlike problem-solving and global strategies, support strategies are executed differently with e-books versus paper texts. When using e-books with touch screens, readers can tap and hold on words with a finger or stylus to take notes, underline, translate, and so on.

ESL and EFL students use support strategies more frequently than English first language (L1) students (Huang et al., 2009; Mokhtari & Sheorey, 2002); furthermore, they have been found to contribute to the most gains in reading comprehension (H. C. Huang et al., 2009). Likewise, J. Huang and Nisbet (2014) found that problem-solving and support strategies were most indicative of high reading proficiency. Although teachers report that global strategies offer the most benefit, ESL students actually report using more support strategies than global ones (H. C. Huang, 2013).

1.3 E-book Impacts on Strategy Use

The research investigating ESL and English as a foreign language (EFL) e-reading strategies is limited, with mixed findings. Some studies conclude that reading strategies are used similarly with e-books and paper texts (e.g., Anderson, 2003; Huang et al., 2009). Others (Chou, 2012) found that students who read e-texts used more skimming and scanning strategies than those who read paper texts, but that overall “[the students] believed that reading screen-based texts limited their use of strategies” (p. 411).

The current literature illustrates that e-books and paper texts may have different impacts on L2 reading comprehension and strategy use. What is not yet clear, however, is exactly what, how, and why they are different. Previous studies either focused on matriculated graduate students (Chou, 2012), utilized out-of-date technology (Kang et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2009), allowed unsupervised reading comprehension tests (Lam et al., 2009), used relatively unnaturalistic methods to track strategy use (Huang, 2013; Huang et al., 2009), or gathered strategy use data though surveys alone (Anderson, 2003; Zhang, 2001). For these reasons, ESL e-book support strategies are worthy of further investigation. The current study is distinctive because it utilizes current technology and triangulates data through observations, supervised comprehension tests, and surveys.

1.4 Research Theory

This study was guided by a sociocultural framework with an interactionist approach. Traditionally, interactionist theory has focused on people's engagement with one another using the target language; however, this approach can be used to conceptualize the ways one engages with a culturally constructed artifact, such as a text or an e-book, as well (Baleghizadeh, Memar, & Memar, 2011; Stevenson, 2010). Using an interactionist approach to guide this study is beneficial because it provides a focus on how e-books and paper texts are used by learners when they self-regulate their individual reading experiences with support strategies in order to receive comprehensible input.

This study is also guided by appropriation theory (Papadima-Sophocleous & Charalambous, 2014), which describes how an innovative artifact, such as an e-book, is foreign until it is incorporated into one's life. Whether an artifact is incorporated hinges upon its proximity to other familiar items; in the case of an e-book, this may be its physical properties and how one can manipulate the text with it. In the current study, the degree to which learners appropriated the e-book to suit their own reading purposes was measured with data from strategy use via observation, reading comprehension tests, and surveys.

2 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

1. Is there a difference in reading comprehension for high-intermediate ESL learners with e-books compared to paper texts?

I expect that the reading comprehension between groups will be similar, contrary to Kang et al. (2009) and Lam et al. (2009), as these studies used currently out-of-date electronic reading interfaces. I believe that as e-book technology advances, the reading comprehension rates between e-books and paper books will equalize. Thus, the reading comprehension rate between e-books and paper books will be similar because of the advances in e-book technology.

2. Is there a difference in the types of support strategies that ESL learners use with e-books compared to paper texts?

I expect that reading with e-books will not affect the types of ESL support strategies used because the four types investigated in the current study (highlighting/underlining/circling [HUC], note-taking, English dictionary use, and bilingual dictionary use) can be implemented naturalistically with both interfaces.

3. Is there a difference in the frequency of support strategies that ESL learners use with e-books compared to paper texts?

I expect that the e-book participants will use a greater frequency of some support strategies, such as looking up words in the dictionary and bilingual dictionary, following H. C. Huang et al. (2009) and H. C. Huang (2013).

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Participants

The participants (n = 22) were full-time high-intermediate ESL learners in a university intensive English program. Participants comprised 13 males and nine females, ages 18–27 (M = 21.14, SD = 2.77). Their L1s were Arabic (n = 6) and Chinese (n = 16). They were randomly assigned to a paper group (n = 11) and an e-book group (n = 11), which took into consideration balance of ages, genders, and L1s.1

3.2 Materials

The materials used for both groups included an institutional review board (IRB) consent form, a demographic survey, and an ESL textbook reading passage about the history of bananas from Practice Makes Perfect: Intermediate English Reading and Comprehension (viewed on different interfaces) (Engelhardt, 2013). The reading passage contained 348 words, requiring four e-book pages or one page of paper. Materials also included reading comprehension pre-, post-, and delayed posttests, adapted from the same book, which contained true/false (see Supporting Information) and multiple choice (see Supporting Information) questions about the main and supporting ideas. Additional materials included strategy mini-lessons; an observation notes form; and postreading surveys which utilized metalinguistic retrospective think-aloud and contained multiple-choice (See Supporting Information), yes/no, and short-answer (See Supporting Information) questions about reading comprehension, strategy use, history of e-book use, and preferences related to e-books or paper texts. This survey method requires verbalization after reading and is one way to reveal what cognitive and metacognitive processes learners experience while reading (Bowles & Leow, 2005).2 Some observation notes sections and survey questions were part of another study.

Additional paper group materials included writing utensils, a paper English dictionary (A. Stevenson & Waite, 2011), a paper Chinese-English bilingual dictionary (Manser, 1999), and a paper Arabic-English bilingual dictionary (Doniach, 1972). Additional e-book group materials consisted of an Apple iPad iOS® 9.1 with a wireless ZAGG® keyboard and the Amazon Kindle® application.

3.3 Procedure

The research assistant met with each participant one-on-one during two sessions (Table 1). The sessions had no time requirements, as such restrictions may have compromised the participants’ reading comprehension, strategy use and/or frequency, and survey responses.

| Session 1 |

IRB consent form Demographic survey Pretest Strategy lesson (E-book or paper text) Reading passage (with observation) Posttest Post-survey |

| Session 2 (1 week later) | Delayed posttest |

3.3.1 Session 1

The participants gave IRB consent and took the demographic survey. Next, they took the pre-test to ensure they had not previously read the passage and to collect a baseline score against which to compare post- and delayed posttest scores.

Then, participants took a mini-lesson on how to implement support strategies using their group's interface. Paper-text participants were prompted to perform each support strategy (highlighting/underlining/circling [HUC], English dictionary use, bilingual dictionary use, and note-taking) through guided practice. E-book participants were prompted to perform each support strategy, as well as use the “comment” and “review” features for note-taking.

Then, participants read the text. While they read, the research assistant collected notes on the types and frequencies of the strategies used. Immediately after they finished reading the passage, they took a posttest (without being able to refer to the passage) and a post-survey.

Afterward, the research assistant collected the paper reading passages and took screen shots of the e-book passages. This way I had additional evidence of how the participants used support strategies. Support strategy use data was triangulated with the participants’ self-reported strategy uses and observation notes.

3.3.2 Session 2

One week later, the participants met with the research assistant to take the delayed posttest.

3.4 Coding and Analysis

To code support strategy use, I reviewed the paper group's passages and counted each instance of HUC. Similarly, I reviewed the screen shots of the e-book group's passages and counted each incidence of highlighting (See Supporting Information, the “underline” and the “circle” features were unavailable). I reviewed the paper texts and counted each instance of note-taking, defined as any characters (etc.) not otherwise counted as HUC. Likewise, I reviewed the e-book screen shots for note-taking (See Supporting Information), measured by instances of the “comment” symbol, which appears on the screen where a note had been taken. The research assistant had counted instances of English (See Supporting Information) and bilingual dictionary (See Supporting Information) use while observing each participant and had tallied them on the observation forms.

The pre-, post-, and delayed posttests were weighed at 15 points, with five true/false questions weighed at one point and five multiple-choice questions weighed at two points.

For the post-surveys, I coded the responses to the close-ended questions quantitatively and those of the open-ended questions qualitatively by noting recurring responses which related to the participant's perceptions of the reading interface, such as “useful,” or “ease” and why, and also by noting their reported use of additional strategies.

I conducted five independent-samples t-tests. They compared background knowledge, reading comprehension, retention, score gains from pretest to posttest, and score decreases from posttest to delayed posttest. Survey results were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Reading Comprehension Results

See Table 2 for the test scores of the two groups and the differences in results over time.

| Score | Changes Over Time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest | Posttest | Delayed posttest | Pretest to posttest | |

| Paper M | 6.09 | 11.09 | 8.27 | 5.00 |

| Paper SD | 1.92 | 4.13 | 3.29 | 4.31 |

| E-book M | 4.27 | 8.91 | 8.27 | 4.64 |

| E-book SD | 2.15 | 2.12 | 3.47 | 3.56 |

An independent-samples t-test compared background knowledge (measured by the pre-test) between groups. There was a significant difference in the pretest scores for the paper group (M = 6.09, SD = 1.92) and the e-book group (M = 4.27, SD =2.15); t(20) = 2.09, p = .05.

A second independent-samples t-test compared reading comprehension (measured by the posttest) between groups. There was not a significant difference in the posttest scores for the paper group (M = 11.09, SD = 4.13) and the e-book group (M = 8.91, SD = 2.12); t(20) = 1.56, p = .14.

A third independent-samples t-test compared text retention (measured by the delayed posttest) between groups. There was not a significant difference in the delayed posttest scores for the paper group (M = 8.27, SD = 3.29) and the e-book group (M = 8.27, SD = 3.47); t(20) = 0.00, p = 1.00.

A fourth independent-samples t-test compared score gains from pretest to posttest between groups. There was not a significant difference in score gains for the paper group (M = 5.00, SD = 4.31) and the e-book group (M = 4.64, SD = 3.56); t(20) = .22, p = .83.

A final independent-samples t-test compared score decreases from posttest to delayed posttest between groups. There was not a significant difference in score decreases for the paper group (M = 2.82, SD = 3.66) and the e-book group (M = .64, SD = 3.67); t(20) = 1.40, p = .18.

4.2 Support Strategy Results

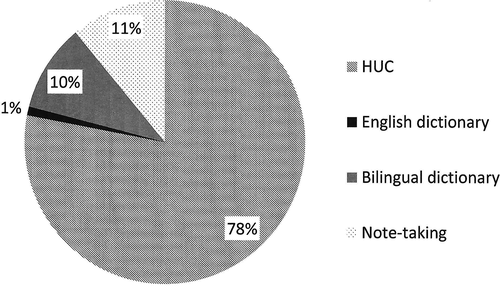

The total support strategy use for the paper group was 262 (M = 23.82, SD = 18.30) (Table 3). Participants varied in support strategy use, from zero to 57 instances. Ten out of 11 participants used a total of four different support strategies: HUC, English dictionary use, bilingual dictionary use, and note-taking (Figure 1). Ten participants used HUC a total of 205 times (M = 18.64, SD = 15.49), its use ranging from zero to 50 instances. Seven participants used note-taking a total of 29 times (M = 2.64, SD = 4.46), its use ranging from zero to 14 instances. One participant used the English dictionary three times (M = 0.27, SD = 0.90). Six participants used the bilingual dictionary a total of 124 times (M = 5.64, SD = 8.22), its use ranging from zero to 32 instances.

| Total | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paper group | 262 | 23.82 | 18.30 |

| E-book group | 160 | 14.55 | 15.49 |

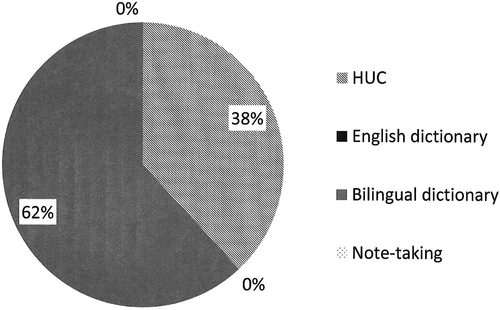

The total support strategy use for the e-book group was 160 (M = 14.55, SD = 15.49) (Table 3). Use ranged among participants, from zero to 42 instances. Eight out of 11 e-book participants used two different support strategies: bilingual dictionary use and HUC. Eight participants used the bilingual dictionary a total of 99 times (M = 9, SD = 10.28), its use ranging from zero to 32 instances (Figure 2). Six participants used HUC a total of 61 times (M = 5.55, SD = 7.70), its use ranging from zero to 24 instances.

4.3 Survey Results

In both groups, the majority of participants who used the bilingual dictionary said it was useful. When the paper group was asked, “Would you use an electronic dictionary if it was possible?” nine participants responded “yes,” one responded “no,” and another said “not sure.” All of the participants who used HUC said it was useful. No participants reported that the English dictionary was useful; however, only one participant—from the paper group—used it. The majority of participants from both groups (63.64%; seven from each group) used additional problem-solving or global strategies.

Seven out of 11 of the paper group participants reported that they have previously used an e-book for learning, compared to 4 out of 11 e-book group participants. When asked which they prefer more, the participants from the e-book group reported to prefer e-books, and the participants from the paper text group reported to prefer paper texts. Despite what group a participant was in, the most frequently provided reasoning for preferring one interface over the other was that it allowed them to use support strategies with greater ease.

5 DISCUSSION

An interesting finding here is that, although average support strategy use varied between groups, average posttest scores, delayed posttest scores, the score gains made from pretest to posttest, and the score decreases from posttest to delated posttest did not.

5.1 Reading Comprehension Discussion

The data support Hypothesis 1 because reading comprehension rates were similar between groups. Independent-samples t-test results suggest a difference between groups regarding pre-test scores; however, this is attributed to one more accurate guess in a true/false, multiple-choice test. Because of the random assignment to groups of a small sample pool and the possibility of successful guessing, I conclude that these results are not meaningful.

Regardless of average pretest scores, independent-samples t-tests revealed no significant difference in score gains from pretest to posttest between groups, meaning that both groups improved scores similarly. Independent-samples t-tests also revealed no significant difference in posttest scores, which provides further evidence that there was no significant difference in comprehension between groups. These results echo those of Kol and Schcolnik (2000), who claim that reading from electronic interfaces will not significantly impact reading comprehension.

Independent-samples t-tests revealed no significant difference in delayed posttest scores, as they were identical. Furthermore, independent-samples t-tests revealed no significant difference in score decreases from posttest to delayed posttest between groups, which provides further evidence that retention was similar between groups.

One limitation here is the small sample size, especially when noting the p-values and range of SDs in each group. Additional research needs to be conducted to confirm the conclusion of this study.

5.2 Strategy Use Discussion

The results do not support Hypothesis 2, as the groups used different types of strategies. The e-book group avoided English dictionary use, using the bilingual dictionary instead. Yet the English dictionary was infrequently used by only one paper group participant.

The e-book group completely avoided using the note-taking feature. This may be due to the limited ways in which the participants could take notes with the e-book, as they could only type notes using the Roman alphabet and not draw or handwrite them.

The e-book participants used the bilingual dictionary most frequently, followed by HUC. These results do not completely align with Huang et al. (2009), who found that when L2 learners read e-texts the most frequently used support strategies were English dictionary use, followed by translating, highlighting, and note-taking, respectively. The different results may be due to differences in proficiency levels, the greater length of study in Huang et al., or the different technology (the e-reader used in Huang et al. required users to click buttons representing strategies, which may have led to a less natural use of support strategies). Additionally, the results do not completely align with Huang (2013), who claimed that L2 learners who use e-texts are more likely to use English or bilingual dictionaries. Again, this study lasted longer and used an interface with the same strategy buttons as in Huang et al. (2009), which may explain the different results.

The results partially support Hypothesis 3. Although the e-book group used the bilingual dictionary more frequently, the paper group interacted with the text through support strategies much more frequently. These findings suggest that ESL learners struggle with e-book support strategy use. My findings do not align with Huang et al. (2009) or Huang (2013), who found that students use support strategies more frequently with e-texts. However, my results do reflect those of Chou (2012), whose participants reported that reading on a computer screen limited their strategy use.

The data revealed a great range in support strategy use among participants, regardless of interface. The standard deviations of the paper group's overall support strategy use and HUC use are nearly as high as their means. The standard deviations of the paper group's note-taking, English dictionary use, and bilingual dictionary use are greater than their means. The data on the e-book group's support strategy use show an even wider range. The e-book group's standard deviations for total support strategy use and for each subtype of support strategy use are greater than the means. These data suggest that other factors, such as individual preference in strategy use, play a greater role than interface.

There are a few noteworthy limitations to the study's design regarding strategy use. It is suggested that future studies provide a stylus for e-book participants because it could positively affect support strategy use and frequency, as it may feel more natural and intuitive for participants who usually use paper texts and writing utensils for learning. Additionally, the e-book application did not include an Arabic-English dictionary, which limited the available support strategies for L1 Arabic participants. Therefore, an e-book with a greater range of languages should be used. Another suggestion for future studies is to use a more rigorous reading sample, as the increased challenge may encourage greater strategy use.

5.3 Survey Results Discussion

The e-book group participants reported to prefer e-books more and the paper group participants reported to prefer paper texts more. Despite what group a participant was in, the most frequent reasoning for preferring the interface he or she used was that it made support strategy use easier. This follows appropriation theory (Papadima-Sophocleous & Charalambous, 2014)—the participants in each group found their interface to be more familiar and thus more useful.

6 PEDAGOGICAL IMPLICATIONS

Based on these results, ESL programs may wish to consider incorporating e-books into their curricula. The use of e-books does not appear to significantly affect students’ reading comprehension, and using them may offer additional benefits, such as reduced burden and cost for the students. Furthermore, e-books could soon replace paper texts in academia (Chou, 2012; Kol & Schcolnik, 2000; Mercieca, 2003), so ESL programs who adapt to this change early may seem more technologically current and appealing to stakeholders.

The implications follow Anderson (2003), who suggests that support strategies are implemented differently with e-books and that L2 instructors should teach these strategies as separate from paper-based ones if the students are to appropriate the technology effectively. This is especially the case with note-taking and English dictionary features, as e-book participants avoided them.

A final implication focuses on affect. The majority of e-book participants (7 out of 11) reported that they had not previously used e-books for learning. After the reading sessions, the majority of e-book participants (7 out of 11) reported to prefer e-books over paper texts for learning, a number which includes six of the seven participants who reported they had never previously used e-books for learning. These results suggest that once students become familiar with e-books and appropriate them, they will prefer them over paper texts. Therefore, instructors should encourage students who are reluctant or new to the technology to try it.

7 CONCLUSION

This study contributes to the fields of second language acquisition and TESOL pedagogy in that it explored whether e-books, compared to paper texts, affected reading comprehension and strategy use among 22 high-intermediate ESL learners. This is an area of scholarly interest that has received inadequate attention as of yet. This was the first study to date that incorporated a contemporary e-book application with an ESL e-book and triangulated data from observations, tests, and surveys. The study's design, implementation, and significance were guided by a sociocultural, interactionist framework and appropriation theory.

The findings are that, even though strategy use and frequency varied between groups, reading comprehension and retention rates (as measured by posttests, delayed posttests, gains from pretest to posttest, and decreases from posttest to delayed posttest) did not. Nearly all of the e-book participants who had never previously used e-books for learning indicated afterward that they preferred them over paper texts for learning. These findings lend support to programs considering the incorporation of e-books into their curricula.

8 THE AUTHOR

Sarah A. Isaacson holds a BA in English with minors in writing and ESL from the University of Wisconsin—Stevens Point, a TESOL Certificate from Michigan Technological University, and an MA in TESOL from Ball State University. She specializes in L2 oral communication strategies, L2 reading strategies, and the impacts of technology on L2 reading.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Dr. Mary Lou Vercellotti for her support and guidance during the writing process. Thanks also to Alicia Miller for her contributions to the research.