Attachment, Well-Being, and College Senior Concerns About the Transition Out of College

This research was supported in part by the Oakland University Graduate Student Research Award.

Abstract

This study examined the relationships among attachment, psychological well-being (PWB), life satisfaction, and concerns about the transition out of college among a sample of college seniors. A path analysis was conducted predicting that PWB and life satisfaction would mediate the relationships between attachment and 3 types of graduation transition concerns: career, change and loss, and support. Significant mediation effects affecting career concerns and change and loss concerns were discovered. Implications for college counseling are discussed.

It is widely accepted that the college experience is a time of significant development with regard to identity (Chickering & Reisser, 1993) and autonomy (Kenyon & Koerner, 2009). It is also often a time of increased leisure activities and moratorium from adult responsibilities (Sherrod, Haggerty, & Featherman, 1993). As such, college students are free to engage in identity exploration and experimentation without the pressures of having to commit to firm decisions (Lemme, 2006). The senior year of college, then, represents a significant transition, during which individuals prepare to leave behind the freedom of the college experience and to assume ownership of adult roles (Hunter, Keup, Kinzie, & Maietta, 2012). Despite the significance of this transition, it has received little empirical attention, particularly when compared with the extensive body of research detailing the psychological impact of the 1st year of college (e.g., Wei, Russell, & Zakalik, 2005). A frequent focus of 1st-year transition literature has been on the important facilitating role of attachment relationships in providing students with a secure base of support from which to explore and adjust to college life (e.g., Kenny, 1987; Wei et al., 2005); based on this association, the present study explored the extent to which attachment dimensions similarly affect the transition out of college.

The Transition Out of College

Existing conceptual literature has described the transition out of college as a turning point with considerable implications for functioning and well-being (Gardner, 1998; Lane, 2013). In support of this position, a small but growing body of qualitative research has empirically identified increasingly ambivalent and negative attitudes among college seniors regarding the transition out of college. For example, a sample of first-generation college seniors reported, in part, the experience of anxiety about the inability to anticipate changes in priorities (Overton-Healy, 2010). College seniors have also described fears of the unknown variables associated with exiting college life and of the pressure to develop career plans and become financially independent (Yazedjian, Kielaszek, & Toews, 2010). Such fears seem warranted, because college graduates often experience considerable difficulties adjusting to life after college (Perrone & Vickers, 2003). Those who are able to secure employment experience significant culture changes (Wendlandt & Rochlen, 2008) and are susceptible to frustrations with adjusting to new learning curves and little structure (Polach, 2004). Those who are unsuccessful in securing employment experience stagnation and frequently describe the 1st year after graduation as a low point in their lives (Perrone & Vickers, 2003). These qualitative studies make useful contributions to conceptualizing the challenges of the graduation transition. Examination of this transition using quantitative methodology, however, remains a gap in the existing literature.

Part of the complexity of life transitions is that they generally involve both anticipated and unanticipated changes (Anderson, Goodman, & Schlossberg, 2012). It would seem that this concept applies to the transition out of college as well. For example, most seniors can reasonably anticipate that the end of college necessitates seeking employment or graduate school; however, graduation involves unanticipated transitions as well, such as losing the structure afforded by the student lifestyle, leaving behind social networks, and feeling pressured by societal expectations that graduates assimilate adult roles (Lane, 2013). Thus, leaving college represents a significant and multifaceted transition process (Overton-Healy, 2010).

This latter point is particularly relevant considering the framework of emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2004), which was articulated partly to explain the delayed progression into adult roles commonly experienced by traditional-age college students. Transitions normatively experienced during emerging adulthood (e.g., leaving home) are critical periods for well-being (Lane, 2015; Weiss, Freund, & Wiesse, 2012). Although many emerging adults are able to seamlessly progress through the numerous life and role changes, others experience identity crisis and distress in response to these changes (Buhl, 2007). Moreover, this age group often engages in risky and impulsive behaviors (e.g., binge drinking) to cope with distress (Scott-Parker, Watson, King, & Hyde, 2011). Collectively, these ideas further underscore the importance of increased attention regarding the transition out of college.

Although the graduation transition is lacking in empirical literature, a wealth of research has accumulated regarding facilitative factors in the 1st year of college. Repeatedly, these studies have identified the importance of attachment relationships. Secure attachments among freshmen have been associated with social competence (Wei et al., 2005), assertiveness (Kenny, 1987), feeling supported in times of stress (Kenny, 1987), and separation–individuation (Mattanah, Hancock, & Brand, 2004). Conversely, insecure attachments predict freshman loneliness and depression (Wei et al., 2005). Although these findings have not yet been applied to the transition out of college, it is possible that attachment theory is equally salient for both transitions.

Attachment Theory

Attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982) contends that the relationships we develop with caregivers beginning in infancy inform our attitudes toward help seeking and new learning in times of distress across the life span. The quality of such relationships manifests in internal beliefs regarding the relative capability of both self and others. Thus, several attachment styles are possible: Individuals can be either securely attached (i.e., positive views of self and other) or possess one of several insecure attachment strategies, of which anxious (i.e., negative views of self and positive views of others) and avoidant (i.e., positive views of self and negative views of others) are most prominent (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998). As a result of these representations, anxiously attached individuals are prone to seek interpersonal enmeshment, whereas avoidantly attached individuals are likely to seek interpersonal isolation (Mallinckrodt, 2000). These attachment strategies are theorized to become activated during times of distress (Fraley & Davis, 1997), thereby affecting one's ability to positively resolve the distressing situation and, ultimately, influencing well-being. Support for this theory has been demonstrated in a sample of emerging adults experiencing various life transitions (Lane & Fink, 2015). Specifically, attachment security was predictive of both psychological well-being (PWB) and life satisfaction.

This latter point positions insecure attachment strategies as a self-reinforcing mechanism. That is, negative beliefs regarding self and/or other are activated during times of transition, diminishing one's ability to effectively cope with the stress of the transition and reinforcing the negative attachment feelings (Fraley & Davis, 1997). When considered in the college context, it is possible that the aforementioned impact of attachment on the freshman transition would continue throughout the college experience, interfering with key college student development outcomes. Such outcomes include emotional regulation, mature interpersonal relationships, identity, and purpose (Chickering & Reisser, 1993), factors that are all affected by attachment (Brennan et al., 1998). These problems could be compounded during the graduation transition, when securely attached seniors could rely on healthy interpersonal functioning, whereas insecurely attached seniors would feel ill prepared given the unresolved distress from previous transitions. Thus, a plausible sequence of relationships would be for attachment to affect well-being, which would affect attitudes regarding the graduation transition.

Such a possibility has never been tested, although doing so would be useful to the college counseling profession. Understanding how attachment predicts both well-being and graduation-related distress could aid college counselors in conceptualizing and working with individuals engaged in this transition. This line of inquiry could also provide some basis for comparing the transition out of college with other emerging adult transitions to which more attention has been given (e.g., Lane & Fink, 2015; Wei et al., 2005).

Present Study

Hypothesis 1: Attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance would be negatively related to PWB and life satisfaction and positively related to the various domains of graduation-related concerns.

Hypothesis 2: Life satisfaction would mediate the relationships between the attachment dimensions and the graduation-related concerns.

Hypothesis 3: PWB would mediate the relationships between the attachment dimensions and life satisfaction.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The sample consisted of traditional-age college seniors enrolled at a medium-size university in a suburban area of the Midwest. Participants were recruited during class sessions and completed surveys in either a paper or electronic format, depending on the classroom format (both versions of the surveys were identical). The sample (N = 182) comprised students majoring in either psychology (n = 90) or education (n = 92). Participants were predominantly White (90.7%) and female (79.7%) and ranged in age from 20 to 29 years (M = 22.50, SD = 1.81).

Instruments

Attachment. I measured attachment using the Experiences in Close Relationship Scale–Short Form (ECR-S; Wei, Russell, Mallinckrodt, & Vogel, 2007). The ECR-S is a 12-item self-report measure derived from the original 36-item Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (Brennan et al., 1998). Its items use a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to assess participant agreement with statements of romantic relationship patterns. The items are evenly divided into two subscales that orthogonally measure attachment anxiety (e.g., “I worry that romantic partners won't care about me as much as I care about them”) and attachment avoidance (e.g., “I am nervous when partners get too close to me”). Each subscale has a possible scoring range of 6–42, with higher scores indicating higher attachment anxiety or avoidance, respectively. The scale's authors reported strong factor structure and acceptable internal consistency estimates derived from several large undergraduate samples (Wei et al., 2007).

PWB. PWB was assessed using the 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5; Bech, Olsen, Kjoller, & Rasmussen, 2003). Each of the items is a positively worded self-statement pertaining to mood and energy (e.g., “I have felt calm and relaxed”). Participants use a 6-point scale (0 = not present, 5 = constantly present) to rate the presence of the emotion over a 2-week period. Item scores are summed and multiplied by four, resulting in a possible scoring range of 0–100. Scores below 50 indicate poor well-being and scores below 28 indicate depression. The WHO-5 has been demonstrated to be unidimensional and to possess adequate internal consistency (Bech et al., 2003).

Life satisfaction. The 5-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) was used to assess life satisfaction. The items contain self-statements (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”) rated on a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The item responses are summed, resulting in a possible scoring range of 5–35, with higher scores indicating higher life satisfaction. The scale's authors reported strong internal consistency (α = .87) and 2-month test–retest reliability (.82), and SWLS scores were highly correlated with other measures of life satisfaction (Diener et al., 1985).

Graduation-related concerns. Graduation concerns were measured using the 31-item Senior Concerns Survey–Short Form (SC-S; Taub, Servaty-Seib, & Cousins, 2006). The SC-S asks participants to rate their degree of concern on a 4-point scale (1 = no concern, 4 = major concern) and contains four subscales: Career-Related Concerns (nine items; e.g., “Adhering to new workplace policies”), Change and Loss-Related Concerns (eight items; e.g., “Not being able to hang out with friends after graduation”), Graduate School-Related Concerns (six items; e.g., “What to do if I am not accepted into graduate school”), and Support-Related Concerns (eight items, e.g., “Having to make sacrifices to be near my family or a significant other”). The item responses are summed for each subscale, with higher scores indicating higher degrees of concern. In an effort to reduce the effect of confounds in the present study, the Graduate School-Related Concerns subscale was not included in the data analysis because an independent samples t test revealed significant differences depending on whether or not individuals in the sample were planning on attending graduate school, t (178) = −4.85, p = .000. Taub et al. (2006) reported internal consistencies of .85 (Career-Related Concerns), .85 (Change and Loss-Related Concerns), and .73 (Support-Related Concerns).

Data Analysis

I conducted a path analysis using Amos 21.0 (Arbuckle, 2012) to test the hypotheses. A theoretical mediation model was developed depicting the relationships among the study variables. Specifically, I drew paths connecting (a) attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance to PWB; (b) attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and PWB to life satisfaction; and (c) attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and life satisfaction to career-related concerns, change and loss-related concerns, and support-related concerns. Because Taub et al. (2006) reported gender differences on the SC-S Career-Related Concerns subscale, gender was controlled for by drawing a path from gender to the career-related concerns variable. Additionally, well-being has been found to increase with age throughout emerging adulthood (Galambos, Barker, & Krahn, 2006). Thus, age was controlled for by drawing paths from age to both life satisfaction and PWB.

With respect to Hypothesis 1, a direct path model (Model A) was tested so that the direct impact of each attachment variable on PWB, life satisfaction, and the graduation-related concerns variables could be examined. To test Hypothesis 2, which referred to the mediating effect of life satisfaction, paths were added to the direct path model connecting life satisfaction to each of the graduation-related concerns variables (Model B). Hypothesis 3, which referred to the mediating effect of PWB, was tested using the full theoretical mediation model, which was created by adding a path connecting PWB to life satisfaction (Model C). The fit of each model was compared using the chi-square goodness of fit test (χ2), with smaller, insignificant values being preferable; the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), which should be lower than .08; and the comparative fit index (CFI), which should exceed .95 (Quintana & Maxwell, 1999).

I tested the significance of the mediation effects using a bias-corrected bootstrap analysis (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). This method evaluates significance by generating 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effects through repeatedly sampling the data set to test the model. The results are bias-corrected in that the estimate is not necessarily the midpoint of the confidence interval. The analysis was set to execute 10,000 bootstrapped samples. Because the confidence intervals are bias-corrected, this method of examining mediation effects offers greater statistical power compared with other methods (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

Results

Data Screening and Transformation

I screened the data for univariate and multivariate outliers and assumptions of normality, linearity, and homogeneity of variance (Meyers, Gamst, & Guarino, 2006). Following the recommendations of Meyers et al. (2006), univariate outliers were transformed using winsorization to equal the nearest acceptable bound. This procedure was applied to two ECR-S Attachment Anxiety subscale cases, two WHO-5 cases, four SC-S Change and Loss-Related Concerns subscale cases, and three SC-S Support-Related Concerns subscale cases. The initial three columns of Table 1 present the resulting descriptive statistics for each instrument scale. Following transformation, each scale was normally distributed (Meyers et al., 2006), and all multivariate assumptions held.

| Variable | α | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ECR-S AAN | .72 | 21.02 | 6.34 | — | ||||||||

| 2. ECR-S AAV | .82 | 15.86 | 6.51 | .26*** | — | |||||||

| 3. WHO-5 | .84 | 57.60 | 19.52 | −.39*** | −.30*** | — | ||||||

| 4. SWLS | .90 | 23.93 | 6.97 | −.48*** | −.35*** | .72*** | — | |||||

| 5. SC-S CRC | .84 | 24.85 | 5.48 | .25** | .01 | −.27*** | −.36*** | — | ||||

| 6. SC-S CLRC | .88 | 14.99 | 5.19 | .42*** | .28*** | −.25** | −.33*** | .50*** | — | |||

| 7. SC-S SRC | .73 | 16.91 | 4.52 | .35*** | .14 | −.16* | −.20** | .61*** | .65*** | — | ||

| 8. Gender | — | — | — | −.08 | −.20** | .05 | .11 | .12 | −.05 | .01 | — | |

| 9. Age | — | 22.50 | 1.81 | −.01 | −.07 | .01 | −.10 | .10 | −.20** | −.09 | −.09 | — |

- Note. Gender was coded so that 0 = male, 1 = female. ECR-S AAN = Experiences in Close Relationship Scale–Short Form Attachment Anxiety subscale; ECR-S AAV = Experiences in Close Relationship Scale–Short Form Attachment Avoidance subscale; WHO-5 = World Health Organization Well-Being Index; SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale; SC-S CRC = Senior Concerns Survey–Short Form Career-Related Concerns subscale; SC-S CLRC = Senior Concerns Survey–Short Form Change and Loss-Related Concerns subscale; SC-S SRC = Senior Concerns Survey–Short Form Support-Related Concerns.

- *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Preliminary Covariate and Correlational Analyses

In addition to the descriptive statistics, Table 1 presents correlations among all study and control variables. As expected, attachment anxiety was significantly related in the hypothesized directions to PWB, life satisfaction, and the graduation-related concerns variables. Attachment avoidance was significantly related in the hypothesized directions to PWB, life satisfaction, and the change and loss-related concerns variable, but was not related to the other graduation-related concerns variables. PWB and life satisfaction were strongly correlated with one another (r = .72), and both were negatively related to each of the graduation-related concerns variables. Finally, the graduation-related concerns variables were all significantly related, with intercorrelations ranging from .50 to .65.

Regarding the control variables, gender and attachment avoidance were significantly related. That is, being male was associated with higher avoidance scores. Additionally, age was negatively associated with change and loss-related concerns. Because of this significant relationship, a path was added to the model to connect age to change and loss-related concerns. No path was added to connect gender and attachment avoidance because the attachment variables were exogenous and did not need to be controlled for. No other associations were found involving the control variables.

Direct Path Model Analysis

In all models estimated, the ratio of the number of cases to the number of free parameters exceeded 10:1 (Kline, 2005). Hypothesis 1 was tested using Model A. The model yielded a poor fit to the data, χ2(17) = 138.98, p = .000, RMSEA = .20, CFI = .74). However, the direct effects from both attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on PWB (β = −.33 and β = −.21, respectively) and on life satisfaction (β = −.41 and β = −.25, respectively) were significant at the p < .01 level or higher. Attachment anxiety was significantly related in the hypothesized directions to career-related concerns (β = .27, p < .01), change and loss-related concerns (β = .37, p < .001), and support-related concerns (β = .34, p < .001). Attachment avoidance, however, was significantly related to change and loss-related concerns (β = .17, p < .05), but not to the other graduation-related concerns variables. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported.

Mediation Model Analyses

Next, the mediation models were tested. Hypothesis 2 was tested using Model B, which added parameters from life satisfaction to each of the graduation-related concerns variables. Model B provided a poor fit to the data, χ2(16) = 56.94, p = .000, RMSEA = .12, CFI = .91. Its fit, however, was significantly better than that of Model A, χ2(1) = 82.04, p = .000. The indirect effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on career-related concerns through life satisfaction (β = .08 and β = .05, respectively) were significant at the p < .01 level or higher. The direct relationship between attachment anxiety and career-related concerns, which was significant in the direct effects model (β = .27, p < .01), was no longer significant after accounting for life satisfaction (β = .11). Additionally, the indirect effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on change and loss-related concerns through life satisfaction (β = .03 and β = .02) were significant at the p < .05 level. The impact of attachment avoidance on change and loss-related concerns, although significant in the direct effects model (β = .17, p < .05), was rendered insignificant after accounting for life satisfaction (β = .13). Attachment anxiety, on the other hand, was still significantly related to change and loss-related concerns after accounting for life satisfaction (β = .31, p < .001); however, this relationship represented a 16% reduction with respect to the same relationship tested in Model A (β = .37, p < .001). Neither of the other indirect effects involving the support-related concerns variable was significant. Hypothesis 2, therefore, was partially supported.

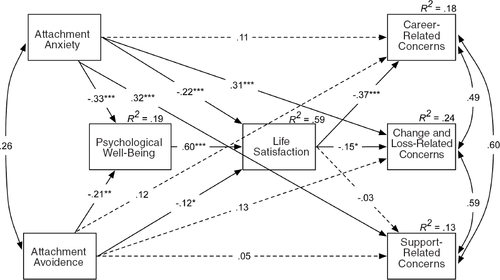

Hypothesis 3 was then tested using Model C, which was created by adding a path from PWB to life satisfaction. This model was an excellent fit to the data, χ2(14) = 18.77, p = .17, RMSEA = .04, CFI = .99. Model fit was significantly improved with respect to both Model A, χ2 (3) = 120.21, p = .000, and Model B, χ2 (2) = 38.17, p = .000. The indirect effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on life satisfaction through PWB (β = −.20 and β = −.13, respectively) were each significant at the p < .01 level or higher. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported. The direct effects of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance on life satisfaction from the testing of Model A (β = −.41 and β = −.25, respectively) were each reduced by roughly half after accounting for PWB (β = −.22 and β = −.12, respectively).

Table 2 provides a summary of all mediation effects in the present model. The table demonstrates that eight indirect effects were statistically significant and three were not. Although not part of the present study's hypotheses, the indirect effect of PWB on career-related concerns through life satisfaction was significant (β = −.22, p < .001), and the indirect effect of PWB on change and loss-related concerns through life satisfaction approached significance (β = −.09, p = .063). These findings suggested that psychological health among college seniors affected their satisfaction with life, which in turn affected their career-related concerns.

| Independent Variable | Mediator Variable | Dependent Variable | β | Ba | SEa | 95% CIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effects Hypothesized to be Statistically Significant | ||||||

| Anxiety | LS | Career | (−.23) × (−.34) = .08b | .07 | .03 | [.03, .13]*** |

| Anxiety | LS | Loss | (−.23) × (−.14) = .03b | .03 | .02 | [.00, .07]* |

| Anxiety | LS | Support | (−.23) × (−.03) = .01b | .01 | .02 | [−.02, .04] |

| Avoidance | LS | Career | (−.14) × (−.34) = .05b | .04 | .02 | [.01, .08]** |

| Avoidance | LS | Loss | (−.14) × (−.14) = .02b | .02 | .01 | [.00, .04]* |

| Avoidance | LS | Support | (−.14) × (−.03) = .00b | .00 | .01 | [−.01, .02] |

| Anxiety | PWB | LS | (−.33) × (.60) = −.20c | −.22 | .05 | [−.33, −.12]*** |

| Avoidance | PWB | LS | (−.21) × (.60) = −.13c | −.14 | .04 | [−.22, −.05]** |

| Indirect Effects not Hypothesized to be Statistically Significant | ||||||

| PWB | LS | Career | (.60) × (−.34) = −.22c | −.06 | .02 | [−.09, −.03]*** |

| PWB | LS | Loss | (.60) × (−.14) = −.09c | −.02 | .01 | [−.05, .06] |

| PWB | LS | Support | (.60) × (−.03) = −.02c | .00 | .01 | [−.03, .02] |

- Note. CI = confidence interval; Anxiety = attachment anxiety; LS = life satisfaction; Career = career-related concerns; Loss = change and loss-related concerns; Support = support-related concerns; Avoidance = attachment avoidance; PWB = psychological well-being.

- aValues based on unstandardized coefficients. bValues estimated by testing Model B. cValues estimated by testing Model C.

- *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The results of testing Model C are presented in Figure 1. In the interest of parsimony, the control variables (i.e., gender and age) are not included in the figure. In this model, gender was significantly and positively related to career-related concerns (β = −.13, p < .05), indicating that women reported higher levels of concern. Additionally, age was significantly and negatively related to life satisfaction (β = −.11, p < .05), as expected, as well as to change and loss-realted concerns (β = −.18, p < .001). Overall, the model explained 18% of the variance in career-related concerns, 24% of the variance in change and loss-related concerns, and 13% of the variance in support-related concerns.

Final Model Showing the Influences on the Transition-Related Concerns of College Seniors

Note. Dashed lines represent nonsignificant parameters. Gender and age are excluded from the model for parsimony.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Alternative Model Testing

Because of the cross-sectional nature of the study, an alternative model (Model D) was tested in which the parameters among the endogenous variables in the study were reversed. Doing so allowed for comparisons to be made between the hypothesized model and another model that could potentially explain the relationships among the study variables. Model D posited that attachment anxiety predicted graduation-related concerns, which, in turn, predicted PWB. PWB, in turn, predicted life satisfaction. Essentially, elevated attachment anxiety and/or avoidance would result in elevated graduation distress, and this distress would result in reduced psychological health, which, in turn, would result in reduced life satisfaction. Model D did not provide an adequate fit to the data, χ2(14) = 34.66, p = .002, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .96.

Discussion

The present study tested a model positing the mechanism through which attachment influences the transition-related concerns of college seniors. Life satisfaction significantly mediated the relationships of attachment anxiety and avoidance on two of the domains of graduation-related concerns (i.e., career-related concerns and change and loss-related concerns), but did not mediate their respective impacts on support-related concerns. Moreover, PWB significantly mediated the relationships of each attachment variable on life satisfaction.

The present study contributes quantitative evidence corroborating the existing graduation literature, which had qualitatively identified the difficult periods of adjustment and negative attitudes surrounding college graduation (Overton-Healy, 2010; Perrone & Vickers, 2003; Yazedjian et al., 2010). The strongest relationships to PWB and life satisfaction were found with career-related and change and loss-related graduation concerns, suggesting that college senior well-being is moderately tied to these aspects of the transition. This finding is reminiscent of those reported by Yazedjian et al. (2010), whose sample reported numerous graduation-related concerns, but those pertaining to the transition into career life were the most salient.

Moreover, the present findings support the contention that attachment security is a key element in the degree of distress that college seniors feel toward the transition out of college. Although this finding had not been proposed prior to the present study, it confirms that the impact of attachment on the graduation transition is similar to its impact on other emerging adult transitions (Buhl, 2007; Lane & Fink, 2015). These relationships suggest that insecure attachments—namely, doubting either one's own capabilities or the ability of others to be helpful in the face of challenging situations—contribute to college seniors' worries about their ability to secure stable careers, overcome the changes and losses of leaving college behind, and develop new support networks outside of the college environment.

An interesting finding was that the impact on each domain of graduation-related concerns was larger for attachment anxiety than for attachment avoidance. This finding suggests that negative representations of self are more detrimental with regard to graduation-related concerns than are negative representations of others (i.e., anxious vs. avoidant attachment; Brennan et al., 1998). It is possible that the reason for this difference is that individuals with avoidant attachment styles seem to actively repress attachment feelings and to lack emotional awareness (Fraley & Davis, 1997). Such individuals, then, may be prone to reporting fewer concerns because of a lack of insight regarding the true amount of distress they are experiencing. Such a possibility, however, requires further testing.

As expected, life satisfaction accounted for a significant portion of the relationships among the attachment variables and two of the three graduation-related concerns variables. This finding supports the hypothesis that securely attached college students are able to develop and maintain satisfying lives during college, giving them confidence regarding their ability to do the same in their lives after college. It is important to note, however, that the magnitude of each statistically significant indirect effect was relatively small. Moreover, for each attachment variable, the indirect effect predicting career-related concerns was over twice as strong as the indirect effect predicting change and loss-related concerns. This finding can be interpreted two ways. Perhaps it is an indication, as many have suggested, that concerns about transitioning into career life are the most psychologically salient concerns for seniors (Taub et al., 2006), as evidenced by the strong association of life satisfaction and the career-related concerns variable. Or, it may also be that change and loss-related concerns share a stronger direct relationship with attachment, preventing life satisfaction from functioning as a mediating variable.

Hypothesis 2 was only partially supported, however, because neither relationship among the attachment variables and support-related concerns were mediated. Although both attachment variables and life satisfaction were significantly related to support-related concerns in the initial correlational analysis, only attachment anxiety was significantly related when all three were concurrently regressed onto support-related concerns in the mediation model analysis. Although this finding contradicted Hypothesis 2, it makes sense on the basis that attachment anxiety is associated with low social self-efficacy and interpersonal dependence (Mallinckrodt & Wei, 2005). These individuals doubt their abilities to handle adversity and believe they must be overly reliant on others to do so. As such, anticipating the changing of support systems would be a particularly salient concern for individuals with elevated attachment anxiety, making the direct relationship among these variables resistant to mediation effects, as was the case in the present study.

With regard to Hypothesis 3, which referred to the mediating effect of PWB on the relationships among attachment anxiety and avoidance on life satisfaction, both indirect effects were significant. This finding supports previous research examining the role of attachment on well-being and life satisfaction during life transition in emerging adulthood (Lane & Fink, 2015). The mediation effect suggests that individuals with elevated attachment insecurity experience comparatively less PWB, culminating in diminished life satisfaction. The indirect effects predicting life satisfaction were notably robust, particularly in comparison with the aforementioned indirect effects predicting graduation-related concerns. Thus, attachment appears to be a major factor in the ability of college students to develop psychologically healthy, satisfying lives.

Interestingly, PWB also indirectly contributed to career-related concerns. That is, individuals who were high in PWB reported higher life satisfaction, resulting in greater confidence about the ability to successfully transition into career life. This finding supports the prior assertion that career-related concerns are the most psychologically relevant domain of concerns that seniors experience as they prepare to transition out of college.

Limitations

Despite the efforts taken to reduce confounding variables in the present study, several limitations remain. The primary limitation was the cross-sectional, nonexperimental research design. In an effort to circumvent this limitation, the present study tested an alternative model, which was determined to provide a significantly worse fit to the data than the primary mediation model. Nevertheless, it would be presumptuous to conclude that the present model is definitive with regard to the sequential paths among variables. Additionally, the findings are limited by the demographics of the sample, of which a disproportionate amount were White (90.7%) and female (79.7%). Moreover, the sample was limited to students majoring in psychology and education, two undergraduate degree areas facing uncertain job prospects, which could have affected their feelings about life after college.

Implications for College Counselors

The present findings are useful for university counselors working with college seniors. Based on these findings, attachment theory seems to provide conceptual insights regarding the graduation transition. That is, seniors with elevated attachment anxiety reported higher career-related, change and loss-related, and support-related graduation concerns, whereas those with elevated attachment avoidance reported higher change and loss-related graduation concerns. Accordingly, given that attachment anxiety equates to negative beliefs regarding self and positive beliefs regarding others (Brennan et al., 1998), counselors working with distressed seniors could attempt to strengthen self-concept as a means of resolving graduation concerns. Similarly, seniors presenting with concerns related to the changes and losses of graduation—which were significantly related to both attachment dimensions—may be well served by this intervention strategy or by interventions that target use of external support resources, because attachment avoidance is characterized by negative beliefs regarding the helpfulness of others (Brennan et al., 1998).

College counselors should also be mindful of the difficulties that insecure attachment strategies pose to the counseling relationship (Fraley & Davis, 1997) and anticipate how those difficulties may interfere with counseling distressed seniors. Mallinckrodt (2000) suggested using the inherent transference and countertransference of the counseling relationship as a corrective attachment experience for insecurely attached clients. Given the present findings, this suggestion might be of use to college counselors working with college seniors who are negatively affected by the graduation transition. That is, the corrective attachment experiences afforded by the counseling relationship may help resolve insecure attachments and, therefore, may also help resolve concerns about leaving college.

Implications for Future Research

Future research efforts should be devoted to confirming the findings with a more representative sample and to testing additional mediating factors in the present model as a means of further understanding the model's associations. Doing so would advance an understanding of the specific mechanisms by which attachment affects the graduation transition. In addition, future research should consider the refinement of the SC-S given that the present study could only use three of the four subscales. Collectively, such efforts would allow researchers to better understand how best to facilitate the transition out of the college experience.