Abstract

Chorioamnionitis is associated with increased lung and brain injury in premature infants. Ureaplasma is the microorganisms most frequently associated with preterm birth. Whether Ureaplasma-induced antenatal inflammation worsens lung and brain injury is unknown. We developed a mouse model combining antenatal Ureaplasma infection and postnatal oxygen exposure. Intraamniotic Ureaplasma Parvum (UP) increased proinflammatory cytokines in placenta and fetal lungs. Antenatal exposure to UP or broth caused mild postnatal inflammation and worsened oxygen-induced lung injury. Antenatal UP exposure induced central microgliosis and disrupted brain development as detected by decreased number of calbindin-positive and calretinin-positive neurons in the neocortex. Postnatal oxygen decreased calretinin-positive neurons in the neocortex but combined with antenatal UP exposure did not worsen brain injury. Antenatal inflammation exacerbates the deleterious effects of oxygen on lung development, but the broth effects prohibit concluding that UP by itself is a compounding risk factor for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. In contrast, antenatal UP-induced inflammation alone is sufficient to disturb brain development. This model may be helpful in exploring the pathophysiology of perinatal lung and brain injury to develop new protective strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Preterm births represent 12% of all live births in the United States and account for >80% of all perinatal complications and deaths (1). Very premature newborns have a high risk for developing long-term injury to lung and brain (1). Chronic lung disease of prematurity or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) remains one of the most frequent sequelae in very premature infants. BPD is characterized by an arrest in lung development, resulting in larger and fewer alveoli (2). Similar structural abnormalities have been demonstrated in newborn rodents exposed to hyperoxia at birth (3). Recent evidence suggests that BPD is an independent risk factor for adverse neurodevelopmental outcome, but the reasons are poorly understood (4). Currently, there is neither prevention nor treatment for BPD. Further advances in our understanding of the mechanisms underlying lung and brain injury are required to increase survival free of morbidity.

Although multifactorial in origin, inflammation plays a major role in the pathogenesis of BPD (5) as indicated by elevated tracheal levels of proinflammatory cytokines in ventilated preterm baboons and human infants developing BPD (6). Antenatal inflammation because of chorioamnionitis is a major risk factor for extreme prematurity. Chorioamnionitis initiates a fetal inflammatory response syndrome (7) that may prime the fetal lung and make it more vulnerable to subsequent postnatal stress (such as mechanical ventilation and oxygen), thus increasing the incidence and/or severity of BPD (6).

Ureaplasma is the microorganism most frequently associated with chorioamnionitis, preterm birth, and pulmonary morbidity (8,9). Despite a strong correlation between the presence of Ureaplasma and inflammation, a causal relationship between Ureaplasma and BPD has not been formally established (9).

Analogous to the pathogenesis of BPD, fetal inflammatory response syndrome has been proposed to be one link between intrauterine inflammation and subsequent impaired neurodevelopment in preterm infants (10). Thus, the same events leading to BPD may cause brain injury.

We developed a mouse model combining antenatal Ureaplasma infection mimicking human chorioamnionitis and postnatal oxygen exposure, mimicking the histopathology of BPD, to explore the hypothesis that adverse antenatal events worsen postnatal lung and brain injury.

METHODS

All animal procedures were approved by the Health Sciences Animal Policy and Welfare Committee of the University of Alberta.

Ureaplasma parvum-induced chorioamnionitis.

Frozen aliquot of Ureaplasma parvum (UP) strain DFK3 (previously labeled Ureaplasma urealyticum serotype 3) was thawed and cultured in 1/10 serial dilution of modified B-broth (11). The B-broth used for injections in this project did not include yeast extract to minimize potential inflammatory reactions. Preliminary in vitro experiments determined that B-broth with and without yeast extract generated the same yield of UP. To further reduce the risk of inflammatory reaction of the vehicle, the aliquot indicating maximal UP growth was diluted with nine parts of saline immediately before injection.

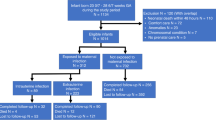

At e13.5, pregnant CD-1 mice (Charles River, Saint Constant, QC, Canada) were allocated to either of four study groups: 1—control (no injection), 2—intraamniotic saline injection, 3—intraamniotic broth (UP vehicle) injection, and 4—intraamniotic UP injection (5000 CFU in each sac). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, and the uterus was externalized through a 12 mm abdominal incision (12). The uterus was soaked with prewarmed saline and 10 μL of study substance was injected into each amniotic sac. The abdominal wall was then closed in two layers. After recovery, mice were given water and food ad libitum. Remaining UP and broth after injection were controlled for contaminating growth. The UP was also cultured in a 1/10 serial dilution of regular B-broth to verify viability and to calculate the number of bacteria that had been injected. Fetal tissues were obtained by C-section at e17.5. For each experimental endpoint, 2–3 litters were used.

Oxygen-induced lung injury.

In separate experiments, mice were allowed to deliver spontaneously and pups were then exposed to either room air or 95% O2 from birth to postnatal age (p) 10.5 in sealed Plexiglas chambers (BioSpherix, Redfield, NY) with continuous O2 monitoring. Exposure of neonatal rodents to 95% oxygen is a well-established model mimicking histopathological features of BPD (3). Dams were switched every 48 h between the hyperoxic and normoxic chambers to prevent damage to their lungs and provide equal nutrition to each litter. Litter size was adjusted to 10 pups to control for effects of litter size on nutrition and growth. Tissues were collected for analyses at different time points as illustrated in Figure 1.

UP culture.

Tissues were stored in B-broth containing glycerol at −80°C. After thawing, the tissue was ground and cultured in serial 1/10-dilutions of regular B-broth (11). Growth of UP was confirmed by urease-test and visualization of UP colonies on agar (13). Bacterial contamination was excluded by cultures on sheep blood agar plates and by visual inspection for cloudiness in the UP culture vials. Bacterial contaminants were absent throughout the study.

Cytokine analysis.

Tissues were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C. Samples were homogenized in 1 mL of 0.1% Igepal/phosphate-buffered saline and centrifuged. Interleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) were analyzed by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Lung myeloperoxidase assay.

Mouse myeloperoxidase (MPO) was measured in P3.5 lung homogenates using an ELISA kit (Hycult Biotechnology b.v. Uden, The Netherlands, catalog number HK210) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Lung histology.

At p14.5, lungs were fixed with 4% formaldehyde through the trachea at a constant pressure of 20 cm H2O. The trachea was then ligated and lungs immersed in fixative overnight at 4°C. Lungs were processed and embedded in paraffin. Serial step sections, 4 μm in thickness, were taken along the longitudinal axis of the lobe. The fixed distance between the sections was calculated so as to allow systematic sampling of 10 sections across the whole lobe. Lungs were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Alveolar structures were quantified on a motorized microscope stage using the mean linear intercept method (14).

Brain histology and immunohistochemistry.

Formalin-fixed brains were embedded in paraffin. Serial sagittal histologic sections were used for cresyl violet staining and immunohistochemistry. Antibodies used for immunostaining were directed against calbindin protein (CaBP, a marker of GABAergic interneurons) (1/2000, rabbit polyclonal; SWant, Bellinzona, Switzerland), calretinin (a marker of a subpopulation of GABAergic interneurons, 1/2000, rabbit polyclonal; SWant), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, a marker of astrocytes) (1/500, rabbit polyclonal; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), myelin basic protein (MBP, a marker of myelin) (1/500, mouse monoclonal; Chemicon, Temecula, CA), tomatolectin (a marker of microglia-macrophages) (1/500, biotinylated lectin; Vector, Burlingame, CA), and cleaved caspase-3 (a marker of apoptosis) (1/200, rabbit polyclonal; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). For immunohistochemistry, deparaffinized sections were microwaved before overnight incubation with the primary antibodies. Antibodies were detected using an avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase kit (Vector), as instructed by the manufacturer. Diaminobenzidine was used as a chromogen. For each marker, at least three sections of each brain were stained in two successive batches. To avoid regional and experimental variations in labeling intensity, for each marker, sections from the different experimental groups were treated simultaneously. All markers were analyzed qualitatively at the levels of the parietal cortex, the underlying white matter, the hippocampus, and the cerebellum. Furthermore, cells or nuclei labeled with CaBP, calretinin, GFAP, tomatolectin, and cleaved caspase-3 were quantified at the level of the parietal cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum. Two fields were analyzed in each experimental group for each animal (five/group) and for each marker by a blinded observer.

Statistics.

Individual values are presented with the median of the group when appropriate. Mann-Whitney two-sample statistic was used to compare differences between medians of two groups. Two-way analysis of variance was used to test for interactions between pre- and postnatal exposures. Data were analyzed with STATA/SE 8.2 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, TX) or with GraphPad4 Prism version for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The level of confidence was 95%.

RESULTS

UP infection.

UP did not cause preterm delivery, maternal loss and did not affect postnatal survival. Greater numbers of UP could be recovered from placenta and fetal lung specimens than originally injected (Table 1). The number of UP recovered from the corresponding fetal lungs varied between individual animals and ranged from none to 104. UP was low or undetectable in p3.5 lungs. Cultures performed on tissues from the three control groups were negative for UP.

UP-induced perinatal inflammation.

Four days after intraamniotic UP injection, inflammatory cells were detected in the fetal membranes (Fig. 2A). The proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and MIP-2 were significantly higher in UP infected placentas compared with controls (Fig. 2B–E).

Placental analyses at embryonic day 17.5. Inflammatory cells (arrows) detected in the fetal membrane of UP infected mice, hematoxylin and eosin staining, magnification ×100 (A). The individual levels of IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C), MIP-2 (D), and MCP-1 (E) in placentas from the four study groups are presented. The lines represent the median of the group. n = 9–10 for each group. Note that y axis does not include zero in (C). Statistically significant differences: * = vs control; † = vs saline; ‡ = vs broth.

Similarly, fetal lungs exposed to UP from the same set of experiments had significantly increased IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, MIP-2, and MCP-1 levels (Fig. 3A–E). TGF-β1 was increased in fetal lungs of all groups that underwent intraamniotic injections (Fig. 3F).

Cytokine levels in fetal lung at embryonic day 17.5. The individual levels of IL-1α (A), IL-1β (B), IL-6 (C), MIP-2 (D), MCP-1 (E), and TGF-β1 (F) in fetal lungs from the four study groups are presented. The lines represent the median of the group (n = 9–10 for each group). Note that y axis does not include zero in (F). Statistically significant differences: * = vs control; † = vs saline; ‡ = vs broth.

Effects of UP-induced perinatal inflammation and postnatal oxygen on lung inflammation.

In separate experiments, animals were allowed to deliver spontaneously and pups were exposed to room air or hyperoxia. At p3.5, pups exposed antenatally to UP had significantly higher MPO levels (Fig. 4A). UP + O2 were also increased but not significantly different when compared with the study groups (Fig. 4A).

MPO and cytokine levels in 3.5 d postnatal lungs. The individual levels of MPO (A), IL-1α (B), IL-1β (C), IL-6 (D), MIP-2 (E), MCP-1 (F) and TGF-β1 (G) in lungs obtained from the four study groups exposed to either room air or hyperoxia after birth are presented. The lines represent the median of the group. n = 5–9 for each group. Note that y axis do not include zero in (C) and (F). Statistically significant differences: * = vs control and equal postnatal exposure; † = vs saline and equal postnatal exposure; ‡ = vs broth and equal postnatal exposure; and § = vs same study group exposed to room air after birth. Interaction of pre- and postnatal exposure detected in (F), p < 0.05.

Pups exposed antenatally to UP or broth had increased lung IL-1α levels (Fig. 4B). O2 alone significantly increased IL-1α (Fig. 4B). Combined UP + O2 exposure further increased IL-1α levels.

Only UP-exposed pups had increased levels of IL-1β at p3.5 (Fig. 4C). O2 alone did not increase IL-1β.

Pups exposed to saline, broth, and UP had elevated levels of IL-6 (Fig. 4D). O2 did not increase IL-6 significantly.

UP or broth exposed pups had increased levels of MIP-2 (Fig. 4E). O2 alone did not increase MIP-2 but combined UP + O2 increased MIP-2 significantly.

UP and broth increased the levels of MCP-1 (Fig. 4F). O2 alone increased MCP-1. Combined broth + O2 further increased the level of MCP-1. There was no significant increase of MCP-1 by combined UP + O2.

Broth increased the level of TGF-β1 (Fig. 4G). O2 alone did not increase TGF-β1 at p3.5.

Effects of UP-induced perinatal inflammation and postnatal oxygen on lung injury.

Antenatal UP or broth alone did not adversely affect lung morphometry at p14.5 (Fig. 5). Hyperoxia impaired alveolarization, characterized by larger and fewer alveoli as quantified by the increased mean linear intercept. Oxygen-induced impaired alveolarization was exacerbated by antenatal exposure to UP and broth.

Lung injury at postnatal day 14.5. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of representative lung sections obtained from the four study groups exposed to either room air or hyperoxia after birth, magnification ×20 (A). In (B) individual results of the mean linear intercept for the four study groups exposed to either room air or hyperoxia after birth are presented. The lines represent the median of the group. O2 = 95% oxygen from birth to p10.5. n = 5 for each group except broth + O2 and UP + O2 (n = 15). Note that y axis does not include zero. Statistically significant differences: * = vs control and equal postnatal exposure; † = vs saline and equal postnatal exposure; § = vs same study group exposed to room air after birth. Interaction of pre- and postnatal exposure detected, p < 0.001.

Effects of UP-induced perinatal inflammation and postnatal oxygen on brain injury.

In the neocortex, there were no differences between groups on the density of GFAP-positive cells (Fig. 6A1). UP alone induced a significant increase in the density of tomatolectin-positive cells (Fig. 6A2) and a significant decrease in the density of CaBP-positive cells (Fig. 6A3) compared with controls or vehicle groups. Oxygen alone had no effect on these parameters and did not worsen the effect of UP. Oxygen alone induced a moderate but significant decrease in the density of calretinin-positive cells while UP and UP + O2 induced a major drop in the density of calretinin-positive cells when compared with control or vehicle groups (Fig. 6A4). At p14.5, no cleaved-caspase-3-positive cell was detected in any of the groups (data not shown).

Brain immunohistochemistry at postnatal day 14.5. Immunohistochemistry (A1–4): Quantification of neocortical cells labeled with antiglial fibrillary acidic protein (A1), tomatolectin (A2), anticalbindin protein (A3), and anticalretinin (A4) in the four study groups. Statistically significant differences: * = vs control and equal postnatal exposure; † = vs saline and equal postnatal exposure; ‡ = vs broth and equal postnatal exposure; § = vs same study group exposed to room air after birth. No interaction of pre- and postnatal exposure detected. MBP immunostaining (B1–4): Representative immunostaining of neopallial labeling with anti-MBP in control (B1), control + O2 (B2), UP (B3), and UP + O2 (B4) p14.5 mice. Bar = 40 μm.

Qualitative analysis of MBP immunostaining showed that O2 alone induced a moderate decrease in the density of MBP immunostaining, whereas UP and UP + O2 induced a major drop in the density of MBP staining when compared with control or vehicle groups (Fig. 6B).

Similar results were observed in the hippocampus and cerebellum except for CaBP immunostaining where O2 alone, when compared with controls, induced a moderate but significant decrease in the density of CaBP-positive cells in the cerebellum (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We show that intraamniotic UP injection in mice causes antenatal infection, transient lung colonization, initiates a mild fetal lung inflammation, without a significant effect on lung injury. UP and broth aggravated postnatal oxygen-induced lung injury. The effect of broth on postnatal lung inflammation and histology is a confounding factor of the study and prohibits us to conclude that UP by itself is a compounding risk factor for BPD. In contrast, antenatal UP exposure specifically induces central microgliosis, a delay in myelination and disturbs neuronal maturation.

Various animal models using intraamniotic endotoxin or Ureaplasma injection suggest that antenatal inflammation primes the fetal lung leading to exacerbated postnatal lung inflammation (15–18). In chronically ventilated preterm baboons, antenatal Ureaplasma infection worsens postnatal lung function (19) and causes more extensive fibrosis compared with noninfected ventilated gestational age-matched controls (20). Rodent models have been limited to either antenatal lipopolysaccharide exposure (21) or postnatal Ureaplasma pneumonia (22,23). The present study was conducted to explore the putative role of Ureaplasma-induced antenatal inflammation on subsequent neonatal lung and brain injury. To accomplish this, a new, clinically relevant animal model was developed. This model was based upon an established BPD-model using newborn mice that are born at the saccular stage of lung development. Newborn mice exposed to hyperoxia develop histologic anomalies seen in human BPD characterized by an arrest in alveolar development (24). For the present work, this model was expanded to include antenatal UP infection, the most common potential pathogen encountered in human chorioamnionitis. In addition, we investigated whether Ureaplasma-induced chorioamnionitis affects brain development, because neurologic impairment is often observed in children with BPD (4).

Ureaplasma are fastidious in regard to culture requirements (13). It was, therefore, important to confirm our ability to cause intrauterine infection in mice. The number of UP recovered from lungs after birth was low, consistent with findings in antenatal Ureaplasma-induced infection in sheep (18). We also confirmed that intrauterine UP infection induces mild antenatal inflammation in the placenta and fetal lungs, in agreement with studies showing an association between Ureaplasma and elevated cytokine levels in amniotic fluid in sheep (18), baboons (19), and humans (25).

The present study expands the information obtained from earlier investigations by combining an antenatal “hit” (UP infection) with a postnatal “hit” (exposure to hyperoxia). Chronic oxygen exposure causes mild lung inflammation and peaks usually at p7.5 in mice (26). In our study, antenatal UP-exposure caused mild postnatal lung inflammation as detected at p3.5 by increased lung MPO and IL-1α and MIP-2 levels-the same cytokines shown to be increased in sheep (18); this inflammation was amplified by hyperoxia.

Hyperoxia impaired postnatal alveolarization in all four study groups; UP by itself did not impair lung development. By contrast, alveolarization was most impaired in the broth and UP groups, indicating that the substances injected in these two groups primed the lungs to be more vulnerable to hyperoxia, lending additional validity to the “multiple hit hypothesis” and providing the first experimental evidence that an antenatal condition can subsequently aggravate chronic hyperoxia-induced alveolar impairment. The mechanisms involved in this process are speculative but may include alterations of the innate immune system emanating from the first insult (27).

The fact that pups exposed to broth only also exerted arrested alveolar development after hyperoxia is a confounding factor that prohibits us to conclude that UP by itself is a compounding risk factor for BPD. Few studies have used multiple control groups including saline and broth to detect the potential effects of the culture vehicle for Ureaplasma. None of the studies have explored the long-term effects of broth. The chronically ventilated baboon studies for example, the model closest to the clinical setting, and the only one in which long-term Ureaplasma effects have been studied, included untreated controls (19) or historical controls only (20) but no broth group (19,20). In the most recent sheep studies, the broth and saline groups did not differ in terms of inflammation in tissues collected during early pregnancy (18), similar to our own findings. However, when extending the observations over longer term, inflammation by broth became evident only days after birth and the deleterious effect on lung development was apparent only after introducing a second insult, hyperoxia.

Ureaplasma requires strenuous culture requirements difficult to circumvent. In an attempt to minimize potential inflammatory effects of broth although still allowing adequate growth conditions for UP, the yeast extract was excluded but horse serum and bovine peptones remained (11). We also diluted the broth with saline before injection to reduce possible adverse effects of these essential UP growth components. The finding that broth has biologic activity is important information when validating experimental models to study the role of Ureaplasma on perinatal morbidity. Ideally, the UP vehicle should be inert to the host animal. The mechanism by which broth exerts the deleterious effect is not clear, but among all other groups, broth groups had the highest levels of lung TGF-β1, (both ante- and postnatally), a growth factor associated with impaired alveolar development (28,29).

To our knowledge, this is the first report of an animal model of Ureaplasma-induced inflammation to include investigations on brain development. We demonstrate that Ureaplasma-induced perinatal inflammation is sufficient in itself to disturb brain development in mice, further supporting the role of inflammatory factors in the pathogenesis of perinatal brain damage. Indeed, it has been suggested that cognitive limitations frequently diagnosed in preterm infants might be associated with an exposure to intrauterine infection (30,31).

Neuropathological studies performed in preterm infants have revealed that gray and white matter abnormalities tend to go hand in hand. With regards to white matter injury, recent studies have shown myelin defect without accompanying oligodendrocyte death (32). In the gray matter, various abnormalities have been reported, including loss of GABAergic interneurons (33) and decreased concentrations of the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin (a marker of interneurons) in the cerebral cortex of brains with diffuse white matter damage (34).

The disturbances of brain development observed in the present study could participate in the process leading to impaired cognitive function. The combined decreased density of calbindin protein-positive and calretinin-positive neurons is in favor of a disturbed production, maturation, and/or survival of interneurons, which play a key role in associative and cognitive functions (35). Furthermore, decreased MBP staining most likely reflects abnormal myelination, which is often observed in surviving premature infants and can participate to limited cognitive functions (36).

Interestingly, UP-induced central microglial activation, suggesting that systemic inflammation led to central inflammation. This microglial effect seemed specific as astroglia was not affected by UP. Microglial activation most likely participated to the observed effects of UP exposure on interneurons and myelin.

Exposure to lipopolysaccharide or inflammatory cytokines is well known to sensitize the developing brain to subsequent hypoxic-ischemic or excitotoxic brain damage (37,38). In contrast, a sensitization effect of infection or inflammation to subsequent hyperoxic brain insult has not been previously reported. In the present study, the observed effects of Ureaplasma on the developing brain were not exacerbated by combined hyperoxia, suggesting that inflammation per se was sufficient to disrupt brain ontogeny. Further studies looking at additional parameters of brain development and maturation will be necessary to address this important question of the potential synergy between inflammation and hyperoxia in the perinatal period.

In conclusion, this novel model, designed to be as clinically relevant as possible, provides evidence for the concept that antenatal events potentiate postnatal events and worsens neonatal outcome. It also demonstrates for the first time that antenatal UP infection disturbs brain development. The use of mice provides the potential advantage to study genetically modified animals. We believe that this model will help in identifying new mechanisms underlying perinatal lung and brain injury and new therapeutic strategies to prevent these morbidities.

Abbreviations

- BPD:

-

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CaBP:

-

calbindin protein

- e:

-

embryonic day

- GFAP:

-

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- MBP:

-

myelin basic protein

- MCP:

-

monocyte chemotactic protein

- MIP:

-

macrophage inhibiting protein

- MPO:

-

myeloperoxidase

- p:

-

postnatal day

- TGF-β1:

-

transforming growth factor beta 1

- UP,:

-

Ureaplasma Parvum

References

Goldenberg RL, Jobe AH 2001 Prospects for research in reproductive health and birth outcomes. JAMA 285: 633–639

Jobe AJ 1999 The new BPD: an arrest of lung development. Pediatr Res 46: 641–643

Rogers LK, Tipple TE, Nelin LD, Welty SE 2008 Differential responses in the lungs of newborn mouse pups exposed to 85% or >95% Oxygen. Pediatr Res, in press

Vohr BR, Wright LL, Dusick AM, Mele L, Verter J, Steichen JJ, Simon NP, Wilson DC, Broyles S, Bauer CR, Delaney-Black V, Yolton KA, Fleisher BE, Papile LA, Kaplan MD 1994 Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993–1994. Pediatrics 105: 1216–1226

Kallapur SG, Jobe AH 2006 Contribution of inflammation to lung injury and development. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 91: F132–F135

Speer CP 2003 Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Neonatol 8: 29–38

Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim KS, Park JS, Ki SH, Kim BI, Jun JK 1999 A systemic fetal inflammatory response and the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181: 773–779

Colaizy TT, Morris CD, Lapidus J, Sklar RS, Pillers DA 2007 Detection of Ureaplasma DNA in endotracheal samples is associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia after adjustment for multiple risk factors. Pediatr Res 61: 578–583

Schelonka RL, Katz B, Waites KB, Benjamin DK Jr 2005 Critical appraisal of the role of Ureaplasma in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia with metaanalytic techniques. Pediatr Infect Dis J 24: 1033–1039

Dammann O, Leviton A 2000 Role of the fetus in perinatal infection and neonatal brain damage. Curr Opin Pediatr 12: 99–104

Robertson JA 1978 Bromothymol blue broth: improved medium for detection of Ureaplasma urealyticum (T-strain mycoplasma). J Clin Microbiol 7: 127–132

Prince LS, Okoh VO, Moninger TO, Matalon S 2004 Lipopolysaccharide increases alveolar type II cell number in fetal mouse lungs through Toll-like receptor 4 and NF-kappaB. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L999–L1006

Waites KB, Katz B, Schelonka RL 2005 Mycoplasmas and Ureaplasmas as neonatal pathogens. Clin Microbiol Rev 18: 757–789

Thebaud B, Ladha F, Michelakis ED, Sawicka M, Thurston G, Eaton F, Hashimoto K, Harry G, Haromy A, Korbutt G, Archer SL 2005 Vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy increases survival, promotes lung angiogenesis, and prevents alveolar damage in hyperoxia-induced lung injury: evidence that angiogenesis participates in alveolarization. Circulation 112: 2477–2486

Ikegami M, Jobe AH 2002 Postnatal lung inflammation increased by ventilation of preterm lambs exposed antenatally to Escherichia coli endotoxin. Pediatr Res 52: 356–362

Kallapur SG, Willet KE, Jobe AH, Ikegami M, Bachurski CJ 2001 Intra-amniotic endotoxin: chorioamnionitis precedes lung maturation in preterm lambs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L527–L536

Kramer BW, Moss TJ, Willet KE, Newnham JP, Sly PD, Kallapur SG, Ikegami M, Jobe AH 2001 Dose and time response after intraamniotic endotoxin in preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 982–988

Moss TJ, Knox CL, Kallapur SG, Nitsos I, Theodoropoulos C, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH 2008 Experimental amniotic fluid infection in sheep: effects of Ureaplasma parvum serovars 3 and 6 on preterm or term fetal sheep. Am J Obstet Gynecol 198: 122 e1–122 e8

Yoder BA, Coalson JJ, Winter VT, Siler-Khodr T, Duffy LB, Cassell GH 2003 Effects of antenatal colonization with Ureaplasma urealyticum on pulmonary disease in the immature baboon. Pediatr Res 54: 797–807

Viscardi RM, Atamas SP, Luzina IG, Hasday JD, He JR, Sime PJ, Coalson JJ, Yoder BA 2006 Antenatal Ureaplasma urealyticum respiratory tract infection stimulates proinflammatory, profibrotic responses in the preterm baboon lung. Pediatr Res 60: 141–146

Ueda K, Cho K, Matsuda T, Okajima S, Uchida M, Kobayashi Y, Minakami H, Kobayashi K 2006 A rat model for arrest of alveolarization induced by antenatal endotoxin administration. Pediatr Res 59: 396–400

Crouse DT, Cassell GH, Waites KB, Foster JM, Cassady G 1990 Hyperoxia potentiates Ureaplasma urealyticum pneumonia in newborn mice. Infect Immun 58: 3487–3493

Viscardi RM, Kaplan J, Lovchik JC, He JR, Hester L, Rao S, Hasday JD 2002 Characterization of a murine model of Ureaplasma urealyticum pneumonia. Infect Immun 70: 5721–5729

Pappas CT, Obara H, Bensch KG, Northway WH Jr 1983 Effect of prolonged exposure to 80% oxygen on the lung of the newborn mouse. Lab Invest 48: 735–748

Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JS, Chang JW, Kim YA, Kim JC, Kim KS 1998 Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity with Ureaplasma urealyticum is associated with a robust host response in fetal, amniotic, and maternal compartments. Am J Obstet Gynecol 179: 1254–1260

Bhandari V, Elias JA 2006 Cytokines in tolerance to hyperoxia-induced injury in the developing and adult lung. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 4–18

Hillman NH, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Kramer BW, Bachurski CJ, Ikegami M, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG 2008 Toll-like receptors and agonist responses in the developing fetal sheep lung. Pediatr Res 63: 388–393

Gauldie J, Galt T, Bonniaud P, Robbins C, Kelly M, Warburton D 2003 Transfer of the active form of transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene to newborn rat lung induces changes consistent with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Pathol 163: 2575–2584

Nakanishi H, Sugiura T, Streisand JB, Lonning SM, Roberts JD Jr 2007 TGF-beta-neutralizing antibodies improve pulmonary alveologenesis and vasculogenesis in the injured newborn lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L151–L161

Dammann O, Kuban KC, Leviton A 2002 Perinatal infection, fetal inflammatory response, white matter damage, and cognitive limitations in children born preterm. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 8: 46–50

Versland LB, Sommerfelt K, Elgen I 2006 Maternal signs of chorioamnionitis: persistent cognitive impairment in low-birthweight children. Acta Paediatr 95: 231–235

Billiards SS, Haynes RL, Folkerth RD, Borenstein NS, Trachtenberg FL, Rowitch DH, Ligon KL, Volpe JJ, Kinney HC 2008 Myelin abnormalities without oligodendrocyte loss in periventricular leukomalacia. Brain Pathol 18: 153–163

Robinson S, Li Q, Dechant A, Cohen ML 2006 Neonatal loss of gamma-aminobutyric acid pathway expression after human perinatal brain injury. J Neurosurg 104: 396–408

Iai M, Takashima S 1999 Thalamocortical development of parvalbumin neurons in normal and periventricular leukomalacia brains. Neuropediatrics 30: 14–18

Mohler H 2007 Molecular regulation of cognitive functions and developmental plasticity: impact of GABAA receptors. J Neurochem 102: 1–12

Back SA 2006 Perinatal white matter injury: the changing spectrum of pathology and emerging insights into pathogenetic mechanisms. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 12: 129–140

Eklind S, Mallard C, Leverin AL, Gilland E, Blomgren K, Mattsby-Baltzer I, Hagberg H 2001 Bacterial endotoxin sensitizes the immature brain to hypoxic-ischaemic injury. Eur J Neurosci 13: 1101–1106

Dommergues MA, Patkai J, Renauld JC, Evrard P, Gressens P 2000 Proinflammatory cytokines and interleukin-9 exacerbate excitotoxic lesions of the newborn murine neopallium. Ann Neurol 47: 54–63

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Drs. Janet A. Robertson and Judy Gnarpe, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Alberta. Dr. Robertson provided the UP strain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by a grant from the Stollery Children's Hospital Foundation, stipends from the Sweden-America Foundation, the Swedish Society of Medicine, a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategic Training Program in Maternal, Fetal and Newborn Health, University of Alberta, the Women and Children's Health Research Institute, Edmonton, AB, and the Karen Hammarlund's Travel Grant, Uppsala University Children's Hospital, Sweden (E.N.), Institut National de la Santé et de le Recherche Médicale (INSERM), Université Paris 7, and PremUP (P.G.), a Canada Research Chair, CIHR, the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research and Canada Foundation for Innovation (B.T.).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Normann, E., Lacaze-Masmonteil, T., Eaton, F. et al. A Novel Mouse Model of Ureaplasma-Induced Perinatal Inflammation: Effects on Lung and Brain Injury. Pediatr Res 65, 430–436 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819984ce

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e31819984ce