Doctors need to be supported, not trained in resilience

BMJ 2015; 351 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h4709 (Published 15 September 2015) Cite this as: BMJ 2015;351:h4709- Eleanor Balme, fifth year medical student, Brighton and Sussex Medical School,

- Clare Gerada, general practitioner, London,

- Lisa Page, consultant in liaison psychiatry, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust and honorary clinical senior lecturer, Brighton and Sussex Medical School

- clare.gerada{at}nhs.net

Abstract

Eleanor Balme and colleagues discuss the findings of a review that they have undertaken into the need for, and potential of, resilience training in doctors

Doctors must be resilient if they are to survive the long and gruelling training and the constant exposure to death, distress, and disability that medicine brings. They need to be adaptable and flexible, able to absorb the pressures of work, the stresses of medicine, and the ethical and moral challenges associated with being a modern doctor. Doctors must be able not only to survive but also to thrive and adapt in the face of adversity. They must be committed, persistent, and confident in their ability, and remain compassionate with patients.1

Resilience is always contextual. It is a complex and dynamic interplay between an individual, the individual’s environment, and sociocultural factors. Any intervention to promote resilience must deal with organisational as well as individual and team issues. Also, just as individuals have degrees of resilience, so do organisations, such that they can survive enormous organisational change or trauma.2

Mental health

Resilience links to a range of psychological maladies from burnout to depression. It also has considerable overlap with the concepts of wellness and wellbeing. Wellness, described as the complete mental, physical, and emotional wellbeing of an individual,3 is a characteristic that can increase resilience, and resilience is in turn also a component of wellbeing. Burnout is associated with a range of negative outcomes, affecting work life and home and social life, including job dissatisfaction and unsatisfactory marriages.4

Resilience is not simply the absence of burnout but promotes dynamic thriving with full engagement. In fact, the emphasis of research on the end stage of failed resilience—burnout—may make it more difficult to plan early intervention to increase resilience.

The prevalence of mental health problems among younger doctors is increasing.5 There are also suggestions that the current generation of doctors are not as resilient as their predecessors and that there needs to be screening for resilience and resilience training embedded into medical student training, with the aim of “toughing up” students for the job ahead.

Research

Resilience is a difficult area to study. There are no consistent definitions; no standardised, valid, or reliable measurements; and no robust studies into what resilience is, what the predictors of resilience are, and whether resilience is related to better patient care.678 This makes screening for individuals who are most likely to show resilience at best an inexact science and at worst discriminatory.

In 2001, clinical psychologist Jenny Firth-Cozens published the results of a longitudinal study to determine the personal and organisational factors that can lead to poor outcomes after stressful events in doctors.9 Her aim was to identify predictors of resilience. She found that personal factors include personality, previous adversities, and coping strategies. Organisational factors include workload and hours.

Firth-Cozens concluded that a combination of both organisational and individual factors predicted an individual’s resilience. The third contributing dimension is sociocultural factors, such as the culture within medicine itself and the rise of blame and claim culture of litigation in wider society.10

Organisational factors

Repeated reorganisations fracture relationships, create anxiety, and predispose those working in an organisation to create scapegoats and develop destructive relationships, where the weakest and those from minorities tend to come off worse.1112

A further impact of repeated reorganisations is that shifts in routines, customs, and practices destabilise the NHS’s complex ecosystem,13 while permanent transitions drain energy, sap morale, and distract workers from the task in hand.14 Continuity matters, for both patients and staff.

Working time restrictions have had a detrimental impact on staff cohesion, decreasing time for handovers. The restrictions have led to “individual clinicians becoming transient acquaintances during a patient’s illness rather than having responsibility for continuity of care.”15 They have also contributed to the loss of firms, which provided continuity and support for training grade doctors. Antisocial hours, shortages of staff, poor leadership, and systems that foster, rather than stop, bullying reduce the ability of organisations and individuals within them to function16 and to deliver effective, safe, and compassionate care to patients.17

Sociocultural factors

The present name, blame, and shame culture in the NHS is making it more difficult for individual doctors to stay afloat.18 The daily onslaught on NHS staff by the media and politicians undermines morale and makes it hard for staff to pick themselves up and face another day. Doctors are also their own worst enemies. The stiff upper lip culture of medicine and stigma associated with doctors suffering psychological problems reduces resilience.19

Individual factors

In 2011, psychologist Clare McCann and colleagues did a literature review of resilience in different health professions, including nurses, social workers, psychologists, counsellors, and doctors.20 They found that being female and maintaining a work-life balance were the only two factors that were consistently, positively related to resilience across all five disciplines.

In four of the five disciplines, self reflection and insight, beliefs and spirituality, laughter and humour, and professional identity were related to resilience, although laughter and humour and professional identity were not investigated in doctors. In other research, the effect of sex differences seems to vary considerably, and different studies of burnout and stress come to differing conclusions, suggesting that different hospital settings or specialties are more important than individual factors.21

Resilience training

Given the importance of resilience, researchers have looked at ways of trying to enhance it. So far research on whether training can enhance resilience has produced a lukewarm “maybe” (see box). A systematic review of resilience among doctors identified only three studies examining resilience training in this group and found such training led to modest benefits.22 These studies incorporated elements of mindfulness or breathing meditation, reflection, self awareness exercises, and shared experience. They were either a one-off intervention or a programme of one to one or group workshops.

Training resulted in variable outcomes including improvement in mindfulness, mood, empowerment, meaning, and engagement with work, self awareness, and knowledge of resilience. Individuals showed decreased levels of burnout and positive changes in empathy and psychosocial beliefs associated with patient centred orientation and behaviours. Participants in resilience workshops stated that they had applied and benefited from this training in both their personal and professional lives.23

These findings are similar to those identified in a review of resilience training programmes in adult populations by health sciences researcher Aaron Leppin and colleagues—that is, of a modest, but consistent benefit, though reporting was poor and methodological quality was low.24

Unified model

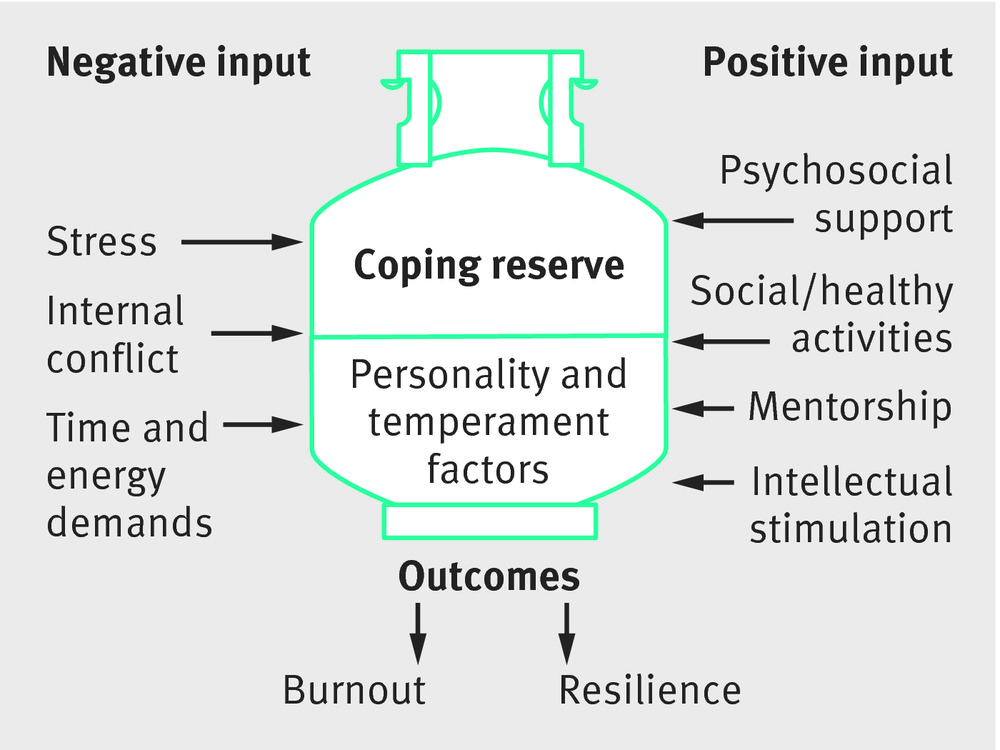

Psychiatrist Laura Dunn and colleagues proposed a conceptual model of medical student wellbeing (see figure).25 The model includes a coping reserve, which can be replenished or depleted with adaptive or maladaptive strategies. Students’ own personality traits, temperament, and coping style create an internal structure within this reserve.⇓

A conceptual model of medical student wellbeing25

The model is a good one and can be used beyond medical school to the lifelong career of a doctor. However, as a model it is incomplete, because it omits the importance of organisational and sociocultural issues, including a stable structure; removal of the culture of blame, name, and shame; and open door policies for line managers. If these issues are not considered, we risk placing the locus of disturbance on to the individual and investing resources in sticking plasters when the necessary treatment is a major operation.

Military analogy

Working in medicine has been compared to being in the army, with the assumption that doctors must become more resilient and face, as soldiers do, the pressures on the battlefield.26 However, the NHS is not a battlefield, doctors are not soldiers, and caring is not a war.

The armed forces value resilience, and it is central to their purpose to have a resilient workforce that is unflinching in the face of fear. For the armed forces, resilience training is embedded in everything they do, from early classroom training, through to fieldwork and beyond. Training in resilience for the armed forces entails techniques such as creating, fostering, and sustaining resilience by deed and example.

A resilient environment

Strengthening resilience in doctors is, of course, important. Ultimately, improving doctors’ resilience should help to decrease the numbers leaving the healthcare system early, as well as improve the patient experience.

Although individual factors play a part in improving resilience and training can improve resilience, they do so in only a small way. Larger effects are achieved through creating posts, career structures, and team working to improve job satisfaction and continuity and through building in time to think and reflect for all staff and redressing the current bullying culture of shame and blame.

If we are to create a resilient environment for healthcare staff, there will need to be structural changes from ward to board. This is something that sadly seems unlikely to happen given the political mindset to blame individuals rather than the system they work in.

Factors aiding resilience21

Intellectual interest

Doctors who maintain intellectual interest and high levels of job satisfaction have greater levels of resilience. There may be confounding factors at play here, since more resilient individuals may choose jobs that are more intellectually interesting. However, this association suggests that where doctors have career progression or job variability or are able to develop additional areas of special interest this will improve retention rates and reduce the risk of burnout.

Self awareness

Self awareness and self reflection help individuals to recognise and accept their limitations and be realistic about what they can do professionally and personally. Self awareness and self reflection also help individuals to establish boundaries in the doctor-patient relationship and to develop self compassion and self forgiveness for errors. Self awareness can be supported and enhanced by mindfulness based stress reduction.

Time management

Resilience promoting behaviours rely on mastering time management, allowing restriction of working hours, ensuring time for the pursuit of leisure activities, and regular holidays. In some of the studies looking across different professional groups doctors were more likely to be dissatisfied with their work-life balance compared with the general population. This varied depending on which medical specialty the doctor belonged to, with general practitioners, radiologists, and public health doctors being most likely to report a good work-life balance.27

Continuing professional development

Engaging in continuing professional development promotes resilience. It does so irrespective of whether this development is structured (doing research or undertaking an academic role), unstructured (reading journals), or related to group activity (practice based small groups, Balint groups, Schwartz rounds, or protected learning time schemes).

Support

Support from others helps to provide a buffer for work related stress. Different types of support are provided by different supporters. For example, close friends and “significant others” can help with active coping, role modelling, and empathy. A spouse or partner can provide emotional support. Challenges and disruptions are more easily managed where there are strong working bonds and mutual trust within the team or organisation. Supportive relationships with work colleagues can help to reduce perceived stress and improve job satisfaction.

Mentors

Mentors help trainees to find the pleasures in their work and are an integral component of professional training. Mentors help with stress reduction and adaptation to change and it is therefore important to make mentors available to all doctors.

Footnotes

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests. CG is a partner of the Hurley Group, an organisation that runs a number of practices and general practitioner walk-in centres across London. She is medical director of the Practitioner Health Programme.