Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the visual and structural outcomes of scleral patch grafting in cases of scleral defect.

Methods

The study was a retrospective interventional case series. Medical records of all patients who underwent scleral patch grafting at a tertiary care centre between 1997 and 2003 for scleral defects were reviewed. After removal of all the devitalized tissue, alcohol-preserved full-thickness sclera was tailored to fit the defect and sutured in place. The graft was covered with a conjunctival flap or amniotic membrane. Structural integrity and visual outcome were assessed as the main outcome measures.

Results

A total of 13 eyes of 13 patients required scleral patch grafting for scleral defects of varying aetiologies, the most common being necrotizing scleritis following pterygium surgery (40%). The patients were followed up for 6–60 months, an average period of 24.3 months. Tectonic success was achieved in 10 eyes (76.9%). Three complications were noted: endophthalmitis, graft necrosis, and graft dehiscence with uveal prolapse. However, no regrafts were needed. Epithelialization and vascularization were seen in the remaining eyes after an average duration of 3–4 weeks. Visual acuity remained stable in the majority (9/13, 60%), improved in one and deteriorated in three eyes.

Conclusions

Scleral grafting with overlying conjunctival or amniotic membrane graft is an effective and simple measure for preserving globe integrity both structurally and functionally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scleral thinning is a well-reported complication following pterygium excision,1 retinal detachment repair, systemic vasculitis,2 high myopia,3 or trauma. In rare cases, it results in staphyloma formation, scleral perforation, and uveal exposure. Reinforcement of thin or perforated sclera is necessary, especially when the choroid is exposed to prevent prolapse of ocular contents and secondary infection. Various types of homografts and allografts have been used in this situation, but none has been uniformly accepted.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Scleral graft has many intrinsic advantages in this scenario as it is readily available from donor eyes, can be easily preserved for months and is strong, flexible, and easy to handle. Sclera has a natural curvature allowing it to neatly blend with host sclera. However, the biggest advantage is that it is avascular and is well tolerated with little inflammatory reaction. On the other hand, failure of scleral homografts has been reported owing to lack of vascularization with resultant necrosis and sloughing.2 In this communication, we report our experience with the use of scleral patch grafts.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective interventional case series of all patients who underwent scleral patch grafting for scleral defects between 1997 and 2003 at a tertiary eye care centre. The parameters recorded were clinical presentation (including preoperative and postoperative visual acuity), past surgical details, systemic diseases, culture results, time lapse between primary aetiology and presentation, details of surgery, length of follow-up, final outcome, and the complications. Successful outcome was defined as structural and visual stability of the eye.

The donor sclera was obtained from Eye Bank eyes preserved in absolute ethanol. Before surgery, it was soaked in ringer lactate solution for 10 min three times, then in Betadine for 10 min, and finally in gentamicin 20 mg/ml solution for 10 min. Operations were performed under peribulbar anaesthesia, except in a 5-year-old child, where general anaesthesia was used. Conjunctiva, Tenon's capsule, and episcleral tissue were dissected carefully to expose the area of scleral defect. All devitalized, infective, and necrosed soft tissue was debrided and the adjacent unaffected conjunctiva preserved. After defining the borders of the surgical bed to be reinforced, the donor sclera graft was fashioned to the appropriate size and thickness. The graft was then secured to the edges of the resection site using 8-0 Vicryl sutures on the scleral side and 10-0 nylon sutures on the corneal side (if needed). The repaired sclera was then covered with a conjunctival flap undermined from the surrounding site or an amniotic membrane graft (AMG) positioned with stromal side down, using 10-0 nylon sutures. The eyes were bandaged after surgery. The bandage was opened the next day and topical steroids, antibiotics, and lubricant eye drops were prescribed and gradually tapered over 1 month.

The structural and visual outcomes were studied and surgical success was defined as tectonic and visual stability of the eye after at least 6 months of follow-up.

Results

A total of 13 eyes of 13 patients underwent scleral patch grafting between 1997 and 2003. Ten patients were male (76.9%) and three were female (23.1%) with an age range from 5 to 76 years. Of 13 eyes, surgery was performed in six right eyes and seven left eyes. No gender predisposition was noted. The most common aetiology was necrotizing scleritis following pterygium surgery (five eyes, 38.5%) (95% CI, 13.3, 66.6) presenting over a wide interval of 2 months to 5 years postsurgery. There was a history of intraoperative adjunctive use of mitomycin C in three eyes. In the remaining two eyes, the status was not known. Of all, three eyes (23.1%) had a history of previous trauma. The other details are summarized in Table 1. The common symptoms in most patients were redness, pain, and soreness. The major indication for surgical intervention was severe scleral thinning with uveal exposure and impending globe perforation. One patient (case 7) revealed an abscess at the site of necrotizing scleritis during surgical exploration. Patch graft was deferred and the patient was started on topical antibiotics and scleral patch grafting was performed after 2 months. No associated systemic diseases were found, except for one known case of rheumatoid arthritis (case 9) that was confirmed by serology.

Postoperatively, in nine eyes (69.3%) visual acuity remained stable. Visual deterioration was seen in three patients (case 5, 3, and 6) and improvement was seen in one eye (case 13). In one eye (case 5), visual deterioration was owing to progression of cataract, for which surgery was planned, but the patient declined surgery at that point. Progressive visual deterioration was noticed subsequent to the development of postoperative endophthalmitis in patient 3. This eye had to be eviscerated after 10 days. Patient 6 had scleral dehiscence with retinal detachment postpenetrating injury for which the patient underwent scleral patch grafting and parsplana vitrectomy. However, the retina remained detached and patient's vision deteriorated.

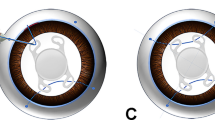

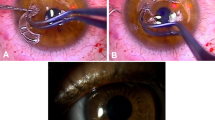

Tectonic success of the scleral patch graft was achieved in 10 eyes (76.9%) (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). However, no regrafts were required. Evisceration was performed in one patient (case 3) following the development of postoperative endophthalmitis. Patient 6 with necrotizing scleritis postpterygium surgery had undergone scleral patch with overlying AMG. However, 4 days later, the AMG disintegrated and the scleral graft became elevated with uveal prolapse. Resuturing was carried out and fresh AMG was applied, after which re-epithelialization was achieved. Necrosis of the scleral graft was noticed 2 months later in the rheumatoid arthritis patient (case 9) and was managed with extensive medical therapy. Re-epithelialization of the ocular surface in remaining cases was achieved 3–4 weeks after the surgery.

Discussion

Human homograft and autograft techniques are commonly employed today to manage ocular diseases that compromise the tectonic stability of the eye. Traditionally, sclera was used as a graft in cases of scleromalacia with impending rupture, scleral ectasias, or traumatic scleral dehiscence.2 In the last decade, many other tissues and synthetic materials have been added to the ever expanding list of reconstructive materials.4, 5, 6 Still no material has been found to be universally acceptable. Varied success has been reported with the use of scleral grafts. There are obvious advantages with the use of sclera (vide supra), the only criticism is that it may become involved in the ongoing necrotic process or being avascular may melt.

Ti et al9 reported favourable results after tectonic corneal lamellar grafting to preserve globe integrity in cases of scleral melting after pterygium surgery. Corneal tissue was selected largely owing to the unavailability of sclera in their surgical set-up. Owing to its transparency, it may not be cosmetically acceptable to the patient. Probably, at present there is no significant benefit of using corneal tissue over sclera if the tissue is freely available.

Split thickness dermal grafts have been shown to provide tectonic support in certain unusual circumstances as in cases of previous conjunctival scarring.6 Dermal grafts have the ability to survive on an avascular surface, are supple, and nonbulky with good tensile strength. Being autogenous, hypersensitivity reactions are not induced. However, they have the disadvantage of being cosmetically unacceptable and unsuitable for use in infective cases and of undergoing extensive vascularization.2 Dermal grafts and numerous other tissues such as fascia lata, periosteum, and cartilage require an additional surgery and thereby have the potential to add morbidity.

In our review of scleral patch grafting for cases of scleral defects of varying aetiologies, favourable structural outcome was achieved in 10/13 eyes. Three patients had complications in the form of endophthalmitis, graft melting, and dehiscence. Postoperative infections can be minimized by its recognition preoperatively, early surgical debridement for clearing infected tissues and deferring patch grafting unless there is a risk of emergent perforation. In the present series, patient 3, who developed endophthalmitis postoperatively, was a high-risk case on account of aphakic glaucoma treated with trans-scleral cyclophotocoagulation with subsequent scleral thinning and corneal oedema. Postoperatively, he developed corneal epithelial defect with infiltration and progressed to fulminant endophthalmitis within a few days. Patient 9, a rheumatoid arthritis patient, developed graft necrosis within 2 months of the patch graft. It was managed medically and regrafting was not required to preserve the structural integrity of the eye. Preoperative screening to rule out systemic vasculitic disorders is necessary. If detected, surgery should be deferred until medical therapy has controlled the primary disease.2

Patient 6 developed graft dehiscence in the postoperative period. In this particular case, graft was covered with amniotic membrane that retracted within 4 days leaving the sclera bare and predisposing the patient to further occurrence of this type. Scleral graft does not contain epithelium and survival is jeopardized on avascular surfaces, so a cover of conjunctival flap is necessary to prevent its necrosis and sloughing. If the adjacent conjunctiva cannot be mobilized, either a free conjunctival flap from the other eye or AMG may be considered.

Amniotic membrane consists of a thick basement membrane and an avascular stroma and is endowed with anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic, and epithelialization promoting properties. At the same time, it is immunologically inert and is very popular for ocular surface reconstruction.10, 11 However, by itself it may not provide adequate tectonic rigidity and is amenable to rapid disintegration and loss. The role of amniotic membrane transplantation (AMT) is only adjunctive to scleral patch grafting as it reduces inflammation and promotes epithelialization. Hwan and Kim12 reported the effectiveness of scleral grafting with AMT for scleromalacia, especially when the adjacent conjunctiva was deficient or not suitable. Rapid re-epithelialization of the ocular surface and marked improvement in visual acuity was noted in most patients. Similarly, safety and efficacy of amniotic membrane alone has been reported to reduce melting in scleral ulcerations.13, 14 The importance of covering the exposed sclera has been previously emphasized in the literature.15 The present experience also underlines the importance of providing a cover for scleral patch by either a conjunctival flap or a properly secured single/multilayered AMT to achieve a viable graft.

In our study, the visual acuity remained stable in most of the patients who received scleral patch graft. Hwan and coworkers12 observed an improvement in visual acuity after scleral graft with overlying AMT. Visual improvement was attributed primarily to reduction in astigmatism by selective removal of sutures on the corneal side of the scleral graft and to improvement of ocular surface and decrease in inflammation.

In conclusion, our clinical results re-emphasize that preserved scleral graft provides adequate functional and structural stability to eyes with jeopardized integrity secondary to scleral defects with acceptable complications.

References

Alsagoff Z, Tan DTH, Chee SP . Necrotising scleritis after bare sclera excision of pterygium. Br J Ophthalmol 2000; 84: 1050–1052.

Nguyen QD, Foster CS . Scleral patch graft in the management of necrotising scleritis. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1999; 39: 109–131.

Bosley WE, Synder AA . Surgical treatment of high myopia. Trans Am Acad Ophthal Otolaryngol 1958; 62: 791–802.

Torchia RT, Dunn RE, Pease PJ . Fascia lata grafting in scleromalacia perforans. Am J Ophthalmol 1968; 66: 705–709.

Koenig SB, Sanitato JJ, Kaufman HE . Long term follow-up study of scleroplasty using autologous periosteum. Cornea 1990; 9: 139–143.

Muariello Jr JA, Pokorny K . Use of split thickness dermal grafts to repair corneal and scleral defects—a study of 10 patients. Br J Ophthalmol 1993; 77: 327–331.

Obear MF, Winter FC . Technique of overlay scleral homograft. Arch Ophthalmol 1964; 71: 837–838.

Saintz de la Maza M, Tauber J, Foster CS . Scleral grafting for necrotizing scleritis. Ophthalmology 1989; 96: 306–310.

Ti S-E, Tan DTH . Tectonic corneal lamellar grafting for severe scleral melting after pterygium surgery. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 1126–1136.

Dua HS, Azuara Blanco A . Amniotic membrane transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 748–752.

Arora R, Mehta D, Jain V . Amniotic membrane transplantation in acute chemical burns. Eye 2005; 19: 273–278.

Hwan J, Kim JC . Repair of scleromalacia using preserved scleral graft with amniotic membrane transplantation. Cornea 2003; 22: 288–293.

Ma DH, Wang S F, Su WY, Tsai RJ . Amniotic membrane graft for the management of scleral melting and corneal perforation in recalcitrant infectious scleral and corneoscleral ulcers. Cornea 2002; 21: 275–283.

Hanada K, Shimazaui J, Shimmuri S, Tsubota K . Multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation for severe ulceration of the cornea and sclera. Am J Ophthalmol 2001; 131 (3): 324–331.

Mansour AM, Bashshur Z . Surgically induced scleral necrosis. Eye 1999; 13: 723–724.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors have no financial interests

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sangwan, V., Jain, V. & Gupta, P. Structural and functional outcome of scleral patch graft. Eye 21, 930–935 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702344

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6702344